Kintpuash (Strikes the Water Brashly), also known as Captain Jack and Kientpoos, was a principal headman of the Modoc tribe during the 1860s and early 1870s. He rose to national prominence during the Modoc War of 1872-1873. Leading a coalition of Modoc bands in a war of resistance against U.S. Army forces and local militia, he held off a numerically superior force for several months.

Kintpuash was hanged by the army at Fort Klamath in southeastern Oregon with three other Modoc leaders on October 3, 1873. He was the only Native American leader to be tried and convicted as a war criminal. And his life highlights many of the central conflicts over emerging federal reservation policies, the continuing practice of forced removals, and the war aims of the federal government, local citizens, and Native groups in the post-Civil War era.

Born in about 1837 in a village along the Lost River in the Modocs' ancestral territory in what is today Oregon, Kintpuash was among the Modoc signatories to the 1864 treaty with the Klamath, the Modoc, the Yahooskin Paiute, and the United States. Under the terms of the treaty, the Modoc people were to relocate to the Klamath Reservation. Kintpuash initially complied with the terms of the treaty, but he later repudiated it when he found conditions on the reservation intolerable and the government unwilling to address the Modocs’ grievances.

In April 1870, Kintpuash and his followers returned to their villages along the Lost River. Back in his homeland, Kintpuash lived near his white neighbors. He rented his lands to them and was well known and welcomed in the town of Yreka, California. Some resettlers desired his land, however, and agitated for his removal.

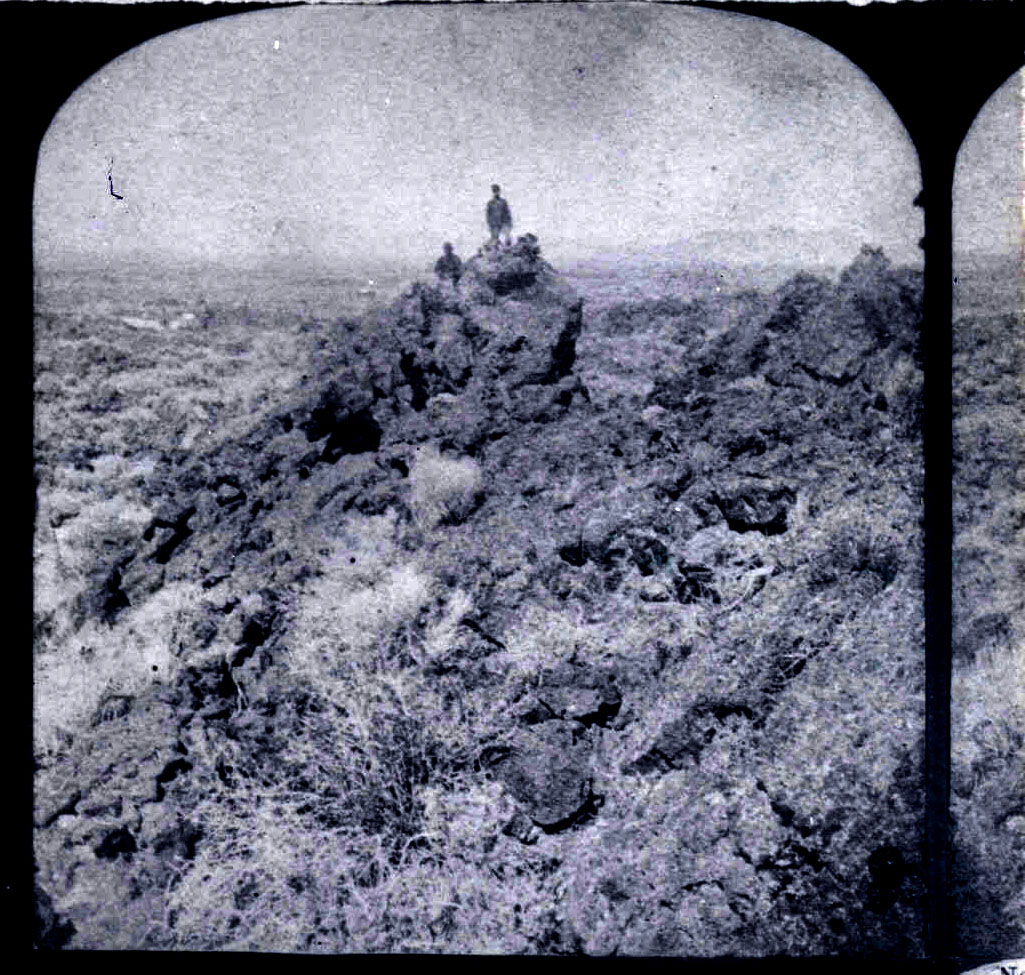

On November 29, 1872, the U.S. Army took advantage of the onset of winter and attempted to force Kintpuash to return to the Klamath Reservation. A brief battle ensued in which a few Modocs and a dozen or so resettlers were killed. The Modocs fled to a traditional site of refuge for the tribe, the lava beds south of Tule Lake, about forty-five miles south of Klamath Falls in California. (The area, known as Captain Jack's Stronghold, was established as the Lava Beds National Monument in 1925.)

Kintpuash had perhaps 150 followers and only 53 warriors as he fought off the much larger army’s assault on his position. On January 17, 1873, in an effort that failed to dislodge the headman, the army sustained 35 casualties; the Modocs sustained none.

Following these failed attempts, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Columbus Delano appointed negotiators, or peace commissioners, to meet with the Modocs. Initially, Kintpuash hoped for a peaceful resolution that would allow him and his followers to remain in their ancestral territory. As negotiations dragged on, however, the Modoc coalition began to fracture as those who were more hawkish advocated violence. In an attempt to manage the fragile coalition of Modocs within the Stronghold, Kintpuash acceded to their plan.

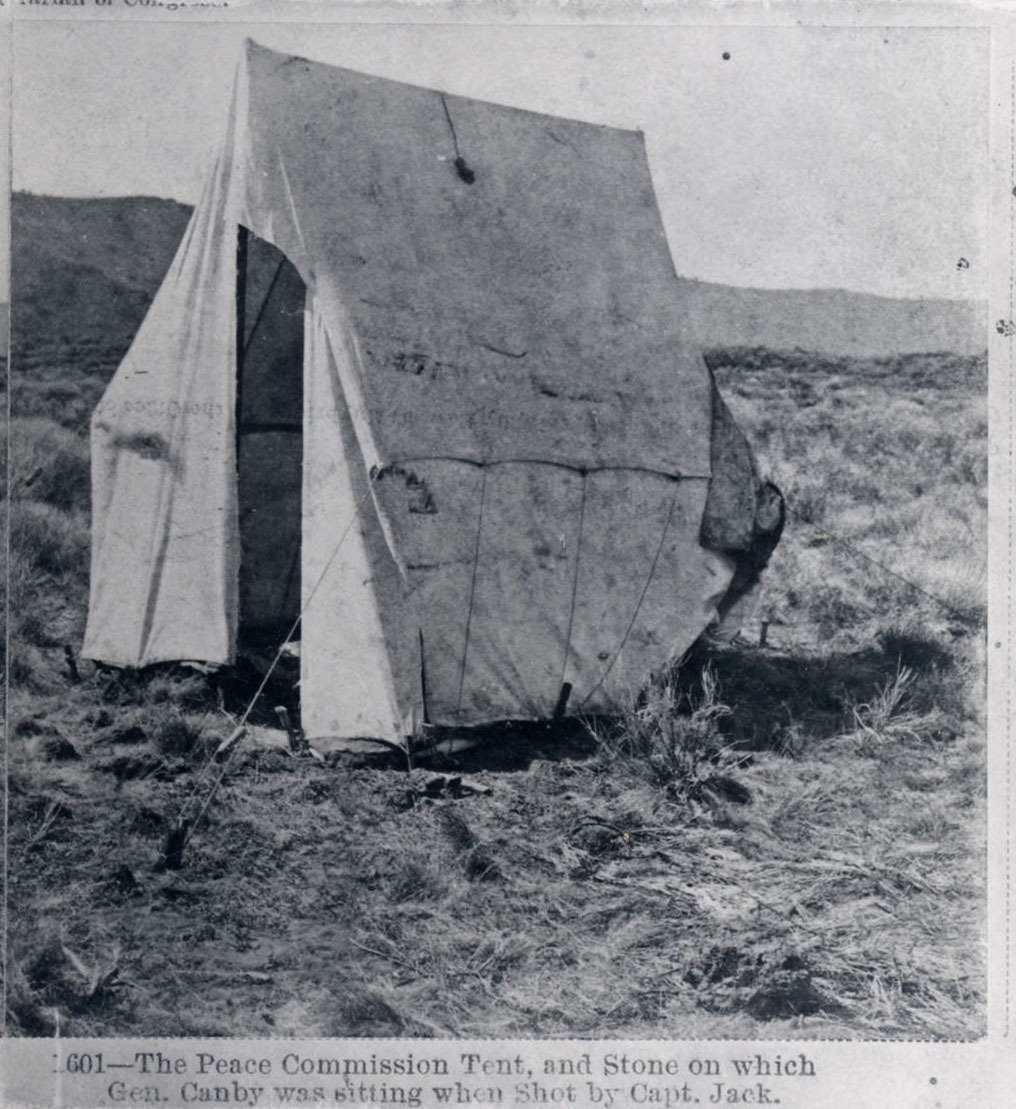

In early April, Kintpuash called a meeting of the peace commissioners with the intention of killing them. During the meeting, on April 11, 1873, he and several of his followers attacked the commissioners, wounding two and killing Reverend Eleazar Thomas and Major General Edward R.S. Canby, the highest-ranking general officer to die in any Indian war.

On April 15, Col. Jefferson C. Davis, with a force of over a thousand soldiers, attacked Kintpuash and his warriors. The Modocs scattered, and Kintpuash evaded capture for several weeks. On May 22, a large number of Modocs surrendered and, in exchange for their lives, agreed to help the army capture Kintpuash. This group, known sometimes as the Hot Creek Band of Modoc Indians, was led by Hooker Jim. A week later, the army caught up with Kintpuash in the Langell Valley, Oregon, east of the lava beds. He avoided capture for two days until, on June 1, he surrendered. Official army reports claim that Kintpuash said: "My legs had given out." His descendants would later remember that he admitted: "I am ready to die."

In July, Kintpuash and five other Modoc defendants faced a military commission, charged with "murder, in violation of the laws of war." Over the course of the trial, Kintpuash sought to explain his actions as self-defensive and representing the will of his people, but he was denied the benefit of counsel and did not cross-examine most witnesses. In addition, four of the six members of the military commission had served under Major General Canby and three had fought against the Modocs.

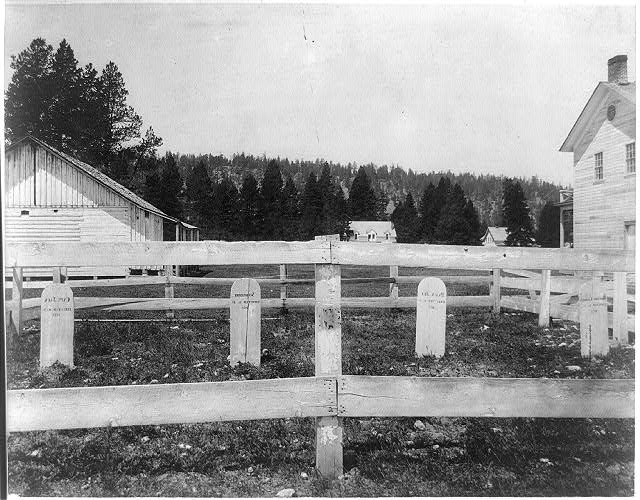

The results were predictable. Kintpuash and the others were found guilty. President Ulysses S. Grant commuted the sentences to life imprisonment on Alcatraz Island, a military prison in San Francisco Bay, for two of the Modocs, Barncho and Slolux. Kintpuash, Schonchin John, Black Jim, and Boston Charley were executed on October 3, 1873.

In accordance with a common practice among U.S. Army personnel stationed in the West, Kintpuash's head was severed and shipped to the Army Medical Museum for study. In 1898, the skull was transferred to the Smithsonian, where it remained until it was repatriated, under controversial circumstances, to the Klamath tribes in the 1980s. Kintpuash and the other executed Modocs are memorialized at the Fort Klamath site.

-

![Kintpuash (also spelled Keintpoos, Keiintoposes), better known as Captain Jack, was a Modoc Indian chief during the 1860s and early 1870s.]()

Kintpuash (Captain Jack), 1873.

Kintpuash (also spelled Keintpoos, Keiintoposes), better known as Captain Jack, was a Modoc Indian chief during the 1860s and early 1870s. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi4357

-

![]()

Kintpuash (Captain Jack) (Modoc), 1864.

Courtesy L.A. Southwest Museum

-

![]()

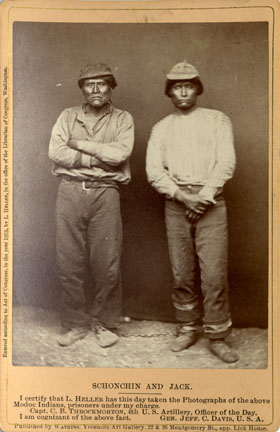

Schonchin and Jack, 1864.

Courtesy Library of Congress

-

![]()

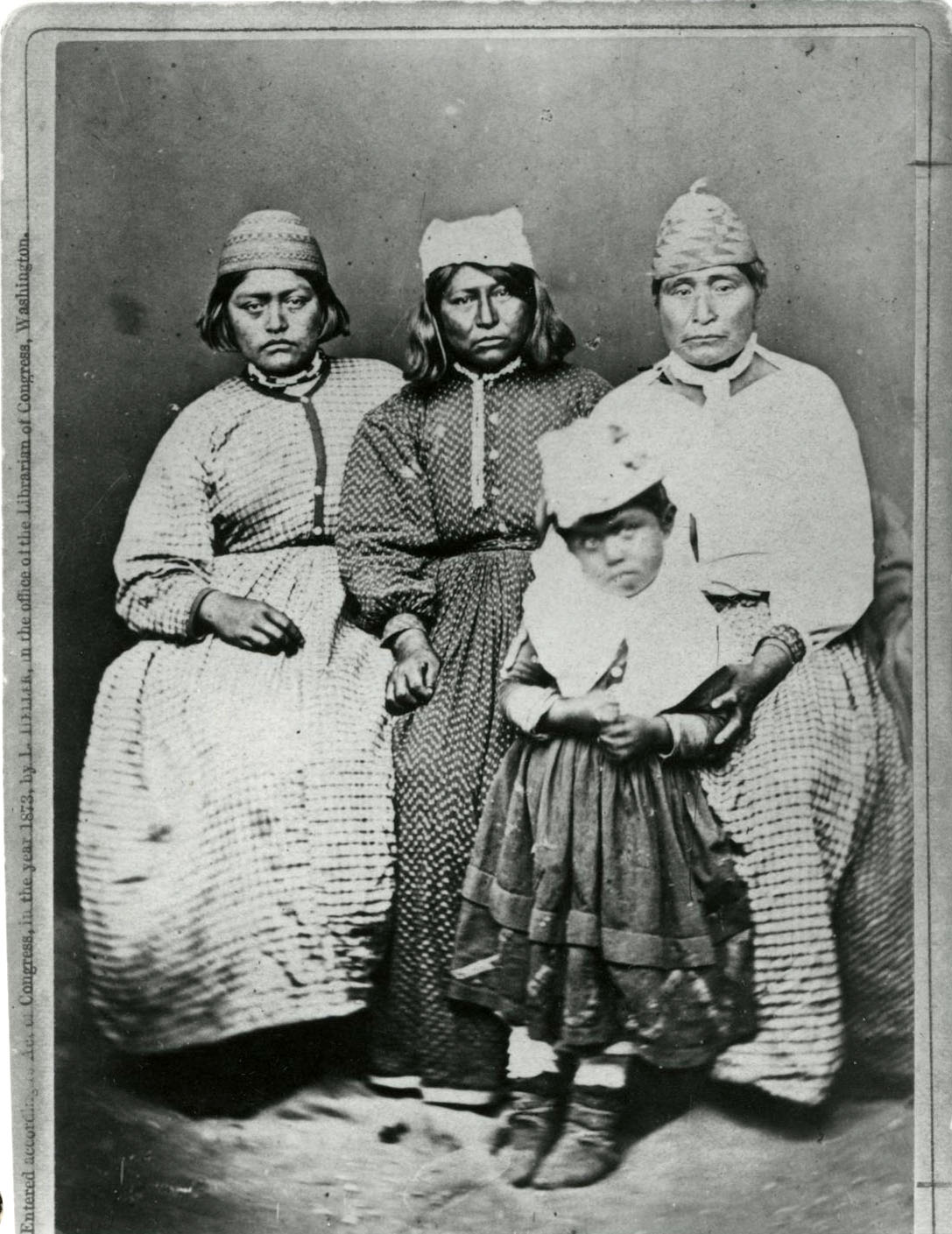

Kintpuash's family, including two of his wives, his sister Mary (center), and daughter, 1873.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi36880

-

![]()

Captain Jack's cave, lava beds, 1873.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 016801

-

![]()

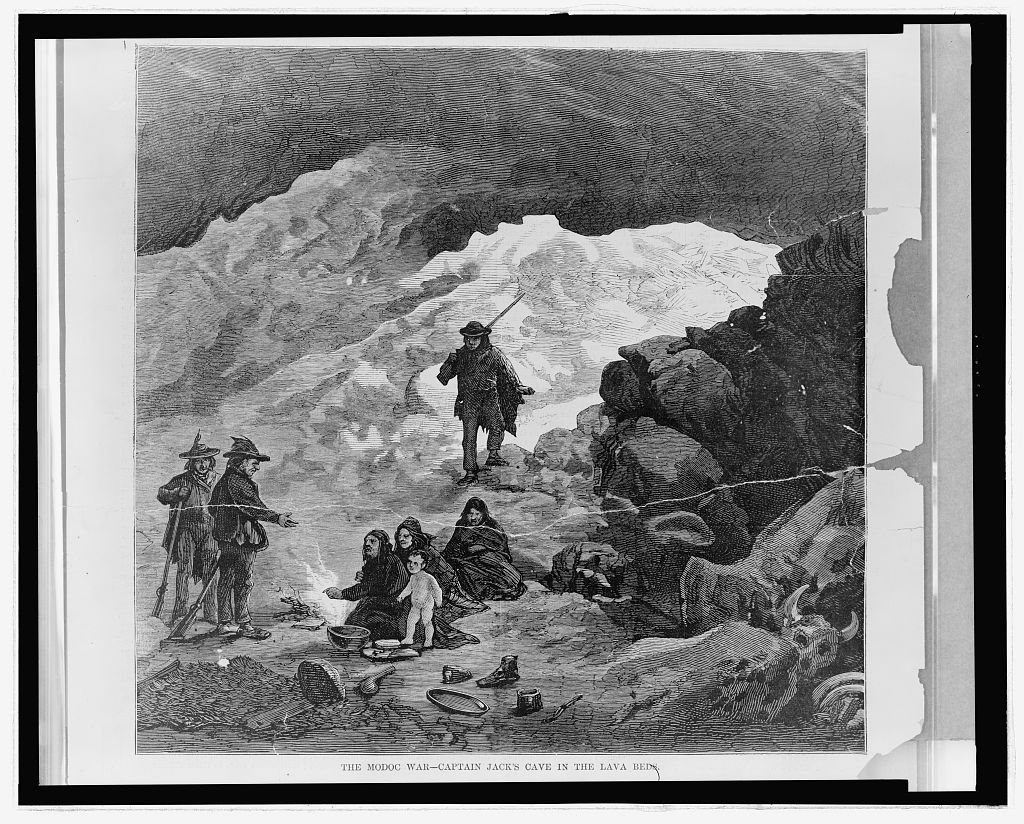

A wood engraving of Capt. Jack's cave in the Lava Beds, Harper's Weekly, 1873.

Courtesy Library of Congress, 2006675168

-

![]()

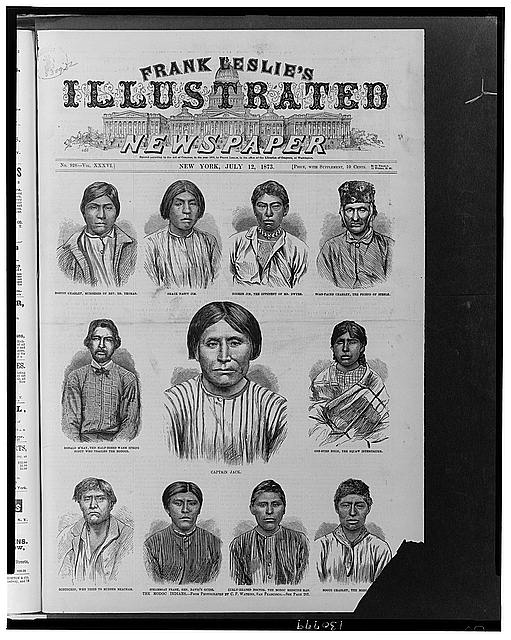

Illustrations of captured Modoc warriors, 1873, Frank Leslie's newspaper.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Itg4KFa

-

![]()

Peace Commission tent where Kintpuash killed Gen. Canby, 1873.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 311, 016800

-

![]()

The graves of the four Modoc leaders hanged by the army, Fort Klamath, 1894.

Courtesy Library of Congress, 2012646846

Related Entries

-

![Fort Klamath]()

Fort Klamath

During the Civil War era, tens of thousands of people immigrated to the…

-

![Modoc War]()

Modoc War

The Modoc War, waged mostly over the winter and spring of 1872-1873, th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cothran, Boyd. Remembering the Modoc War: Redemptive Violence and the Making of American Innocence. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Foster, Doug. "Imperfect Justice: The Modoc War Crimes Trial of 1873." Oregon Historical Quarterly 100:3 (Fall 1999): 246-87.

James, Cheewa. Modoc: The Tribe That Wouldn't Die. Happy Camp, California: Naturegraph, 2008.

Murray, Keith A. The Modocs and Their War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959.