Kinzo Suzuki was an early settler of Oregon who arrived in Portland as a political refugee from Japan—an immigration path that was atypical among early Japanese immigrants, who most often came to the United States as laborers. Though he began life in Portland as a servant and lamplighter, Suzuki went on to become a career diplomat for the Japanese government. Some sources, including a statement by Oregon Representative Al Ullman in the Congressional Record, cite Suzuki as one of three survivors of a shipwrecked Japanese fishing boat that landed at Cape Flattery near the Strait of Juan de Fuca around 1834. That account has been disputed by other historians.

Suzuki came to the attention of Elisha E. Rice, the first American consul in Hakodate, Japan, after Japan’s Treaty of Kanagawa opened the fishing village (as one of two ports) to foreign trade in 1854. Suzuki “voluntarily threw himself into the arms of the American consul for protection,” according to an account by H.C. Leonard, a Portland merchant visiting Hakodate.

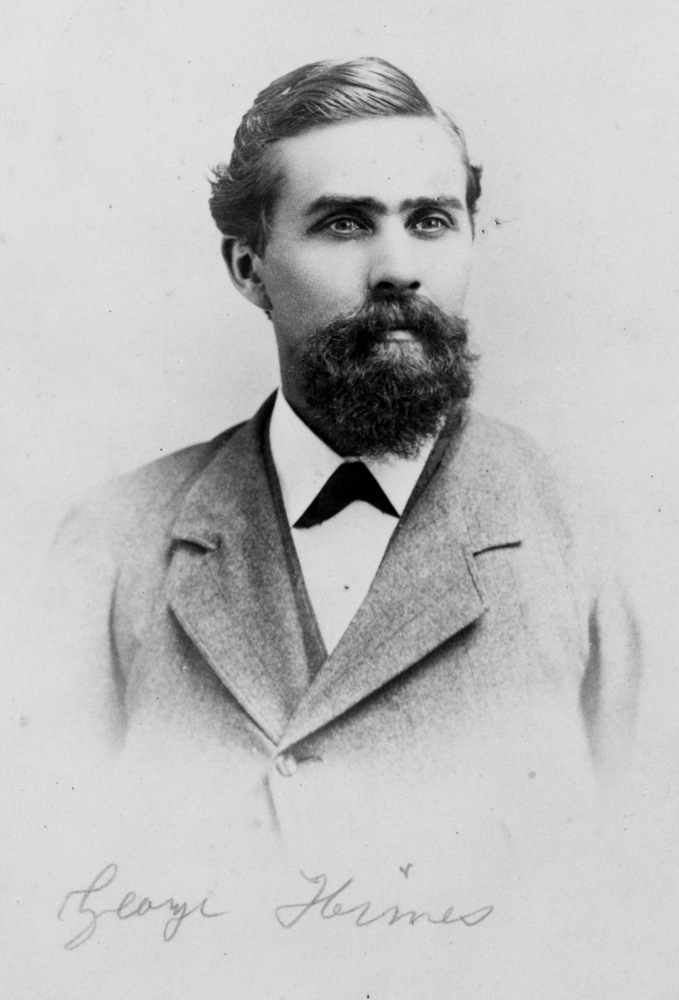

A fluent English speaker who carried two swords, a privilege of the samurai warrior class, Suzuki reportedly feared he would be arrested and had stowed aboard a small Japanese junk from Edo (later Tokyo) to Hakodate. He may have been a political opponent of the Tokugawa government, which arrested more than one hundred dissenters during the Ansei Purge of 1858-59. The scant details of Suzuki’s life are largely based on the memoirs of two Portland businessmen, printer George Himes and gasworks owner Leonard. American Consul Rice, who had given Suzuki refuge in Hakodate for a year, arranged his escape in 1860 aboard the Orbit, Leonard’s Portland-bound vessel.

Suzuki worked for Leonard for almost eight years, first as manager of the household and then as a lamplighter for Portland Gas & Coke Company, Leonard’s gasworks business with John Green (now Northwest Natural). He also attended Portland’s Central School for three years, where “his natural ability and studious habits won for him the head of his classes in mathematics and history,” according to George Himes, the Oregon Historical Society’s first curator.

During the winter of 1866, a chance meeting with an emerging Japanese leader changed the course of Suzuki’s life. While in San Francisco to boost his health, Suzuki happened to meet friends from Japan who were on their way to Washington, D.C., as attachés of Japanese statesman Hirobumi Ito. Ito was reportedly astonished to meet a countryman who “could speak English as fluently as a native American.” Before he returned to Japan the following spring, Ito invited Suzuki to accept a government appointment.

With Leonard’s encouragement, Suzuki accepted Ito’s offer and returned to Japan, after an absence of nearly eight years from his home. This was a fortuitous decision, as Ito undertook government assignments in the United States and Europe and became an advocate for introducing Western models of finance, politics, and constitutions in Japan, eventually serving as its first prime minister in 1885. In 1867, Suzuki was appointed secretary to the Japanese Embassy at the Court of St. James’ (the British royal court in London), where he lived for about five years. One account reports that he also had assignments in Spain and Portugal.

Suzuki was in his forties when he offered his resignation due to ill health, but the Japanese government instead assigned him to a foreign office in Tokyo with hopes he would regain his health. After another year, he was named secretary to the new ambassador in Washington, D.C. Several days before his departure, however, Suzuki died in Tokyo in 1882.

-

![Read entire document under Documents]()

George Himes's account of Kinzo Suzuki.

Read entire document under Documents Courtesy Oregon HIst. Soc. Research Lib., Mss1462 F1

Documents

Related Entries

-

![George Himes (1844-1940)]()

George Himes (1844-1940)

Historian, archivist, printer, and journalist George Henry Himes served…

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

-

![Japantown, Portland (Nihonmachi)]()

Japantown, Portland (Nihonmachi)

Portland's Japantown, or Nihonmachi, is popularly described as having e…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Farwell, Byron. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Gaston, Joseph. The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912. Vol. 2. Chicago: S.J. Clarke, 1912.

Himes, George Henry. “An Account of the First Japanese Native in Oregon.” Oregon Historical Society, Ms 1462, c. 1904. It should be noted that Himes’ account is based on his memories of Suzuki as well as his interview of H.C. Leonard at 81.

Ito, Kazuo. Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America. Seattle: Executive Committee for the Publication, 1973.

Iwata, Masakazu. Planted in Good Soil: A History of the Issei in United States Agriculture. New York: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 1992.

Naosuke, Ii. Nakasendoway: A Journey to the Heart of Japan.

Royal Geographical Society. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society. Vol. 17. 1872-1873.

Ullman, Al. “Tributes to the Japanese American Contributions to the United States.” Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, June 29, 1972, 118:107.

Yasui, Barbara. “The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834-1940.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (September 1975), 228.