Klamath Falls, the county seat of Klamath County, is on the southeastern shore of Upper Klamath Lake about seventeen miles north of the California-Oregon state line. Known by some as Oregon's City of Sunshine for its up to 300 sunny days a year, the city is located in the northeastern Klamath River watershed. The economy of Klamath Falls is historically based in agriculture, livestock, and timber, but in the twenty-first century it relies on aviation, education, energy, health care, manufacturing, and outdoor recreation. In 2020, Klamath Falls had about 21,800 residents and spanned 20.14 square miles, making it the second largest city in area in southern Oregon.

During the early to mid-nineteenth century, white resettlers arrived in the area, a place where Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin-Paiute people lived for thousands of years. In 1864, the Klamath Tribes signed a treaty with the U.S. government, which Congress ratified in 1870. The treaty ceded more than 23 million acres of tribal lands to the federal government and established a reservation on Klamath territory east of the Cascade Mountains. Congress terminated the government’s recognition of the Klamath Tribes in 1961 and authorized the sale of tribal lands; recognition was restored in 1986.

Klamath Falls had its beginnings in 1867 as Linkville, an outpost established by New Yorker George Nurse, who arrived in Oregon in the early 1860s. The first cattle ranch was established in 1866. By 1872, forty people lived in the settlement; by 1877, William S. Moore had built a sawmill, and George T. Baldwin (later a judge and state senator) had opened the Tin Shoppe. The cattle industry took hold despite setbacks in the severe winters of 1879–1880 and 1889–1890. The Linkville Star was established in 1884 (later renamed the Klamath Star), and the Express began publishing in 1892.

Linkville was designated the county seat in 1882, but growth of the town stalled after an 1889 fire destroyed much of the business district. Renamed Klamath Falls in 1893, the town of 2,500 people was incorporated in 1905. Community leaders proposed the new name to describe the series of rapids on the Link River, where waters from Upper Klamath Lake spilled over a natural riverbed.

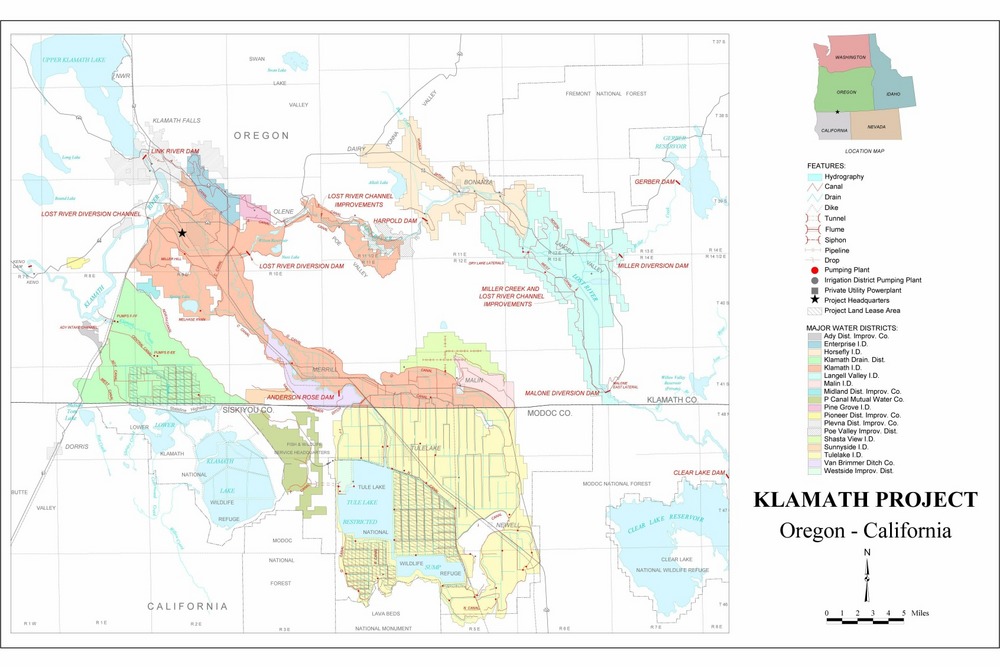

Klamath Falls underwent a dramatic change after the National Reclamation Act of 1902 provided for the conversion of swamps and lakes to irrigable land. In 1905, the federal government announced the Klamath Basin Project, which drained lakes and wetlands for cultivation using a network of dams and canals, increasing economic development and migration to the area. The Express, renamed the Morning Express, became a daily in 1907, and for a time other dallies represented the political and geographic interests of the city. By 1942, the Evening Herald and the News had merged, and the Herald and News became the only paper in town.

The Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in Klamath Falls in 1909, connecting the town to Weed, California, and a northern railroad extension to Eugene was built in 1926. Box shook—milled strips of pine wood used to make shipping boxes for fruit and vegetables—was the first industrial use of the area's Ponderosa pine stands, and box factories lined the shore of Lake Ewauna. For a time, Klamath Falls reportedly produced more box shook than anywhere else in the world.

Klamath Falls grew rapidly and was the fourth largest city in Oregon in 1930 and 1940. In the 1930s, a city-owned airport opened five miles to the southeast. It was named Kingsley Field in 1957 in honor of Air Force Lt. David R. Kingsley, who was killed in World War II. The airport has been called the Crater Lake–Klamath Regional Airport since 2013 and is the home of the Kingsley Field Air National Guard Base and the 173rd Fighter Wing of the Oregon Air National Guard.

For much of the twentieth century, the Weyerhaeuser Company was a major stakeholder in the Klamath Falls area, at one time employing over a thousand people. The company dismantled its sawmill in 1992 and sold the rest of the operation in the area to Collins Products in 1996. The JELD-WEN Corporation, a manufacturer of doors and windows, opened in Klamath Falls in 1960. After owner Richard Wendt died in 2010, a majority share of the company was sold to the Onex Corporation, which moved the headquarters to North Carolina in 2015. In 2024, JELD-WEN still employed about a thousand people in Klamath Falls.

Klamath Falls has historically suffered from high unemployment, with a median per capita income of $29,201 in 2018–2022 and a 22 percent poverty rate in 2020. Yet there are bright economic spots, particularly in health care and education. The Oregon Vocational Institute (now Oregon Institute of Technology), founded in 1947 to help retrain World War II veterans, has a residential campus in Klamath Falls and programs in engineering, health technology, and applied sciences. In 2023, the Sky Lakes Medical Center (established in 1965 as the Merle West Medical Center) was the largest employer in the area, with about 1,700 workers.

Klamath Falls is in a geothermal resource area—a fifty‐mile‐long, ten‐mile‐wide underground reservoir of hot water. Indigenous people long made use of heat from the reservoir, and geothermal wells have been used in the area for over a century. A downtown geothermal heating system began operating in 1984, and the city’s geothermal utility system provides heat to more than twenty commercial, nonprofit, and government facilities.

In 2001, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ordered that Klamath Project irrigation water be shut off due to an Endangered Species Act requirement and concerns over several species of fish. Eighteen thousand people in what was called the Bucket Brigade protested. Irrigation was resumed in 2002. In 2021, drought conditions led federal officials to shut the gates to the Klamath Basin Project irrigation system. The conflict over the Klamath Tribes’ water rights, agricultural needs, and ESA requirements led to legal disputes over jurisdiction. The issue was resolved in favor of the federal government and the Tribes when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal from the Klamath Irrigation District. Dam removal began on the Klamath River in October 2023; when completed, it will be the largest dam removal in U.S. history.

The lack of water has not been the only stress on the environment. A series of earthquakes shook the area in 1993, the largest one centered about sixteen miles northwest of Klamath Falls. Measured at 6.0 on the Richter scale, it caused more than $7.5 million dollars of damage to unreinforced masonry buildings in the city. In addition, forest fires, such as the Bootleg Fire in 2021, affected the city’s air quality and livability.

In 2023, Smithsonian Magazine named Klamath Falls one of the fifteen best small towns to visit, touting its lakes, rivers, and wildlife areas; its hiking trails; and its location on the Pacific Flyway. The city also attracts filmmakers, beginning with the 1924 Rin-Tin-Tin film Find Your Man. Its cinematic history also includes Tom McCall’s 1958 documentary, Crisis in the Klamath Basin, and the 2019 comedy Phoenix, Oregon, in which Klamath Falls is portrayed as the City of Phoenix.

-

![]()

Main St., Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi16074, photo file 618a

-

![]()

Linkville, 1886 (Klamath Falls).

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi56585, photo file 618a

-

![]()

George Nurse, c. 1900.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, CN 012867, Oregon Journal

-

![]()

George Nurse's home, two-story house in the right, Linkville (Klamath Falls).

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 47514. photo file 618a

-

![]()

Freight wagons in Klamath Falls headed to Jacksonville, 1896.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 988D047, photo file 918a

-

![]()

Linkville/Klamath Falls, c. 1890s.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 25738A, photo file 618a

-

![]()

Reames, Martin & Co., Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi4517, photo file 618b

-

![]()

Hotel Linkville (Klamath Falls).

Oregon Historical Society Research Library,ba011344, photo file 616b

-

![]()

Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba011266, photo file 618a

-

![]()

High school, Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, bs011304, photo file 618b

-

![]()

Crowd at the reopening of the First State Savings Bank, Klamath Falls, 1921.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba011282, photo file 618a

-

![]()

Main St., Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 53199 photo file 618a

-

![]()

Powerhouse on the Link River, Siskiyou Light & Power Co..

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba011303, photo file 618b

-

![]()

Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi16101, photo file 618a

-

![]()

Linkville public school (Klamath Falls).

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba011320, photo file 616b

-

![]()

Oregon Bank Building, Klamath Falls, 1930.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Oregonian, ba011299, photo file 618b

-

![]()

Great Northern train depot, Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library,Orhi74161, photo file 618b

-

![]()

Big Basin Lumber Co., Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, photo file 618b

-

![]()

Modoc Tribe float in Klamath Railroad Day parade.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba011354, photo file 618c

-

![]()

Early Klamath Falls (Linkville) on the lake.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 2905 66843, photo file 618a

-

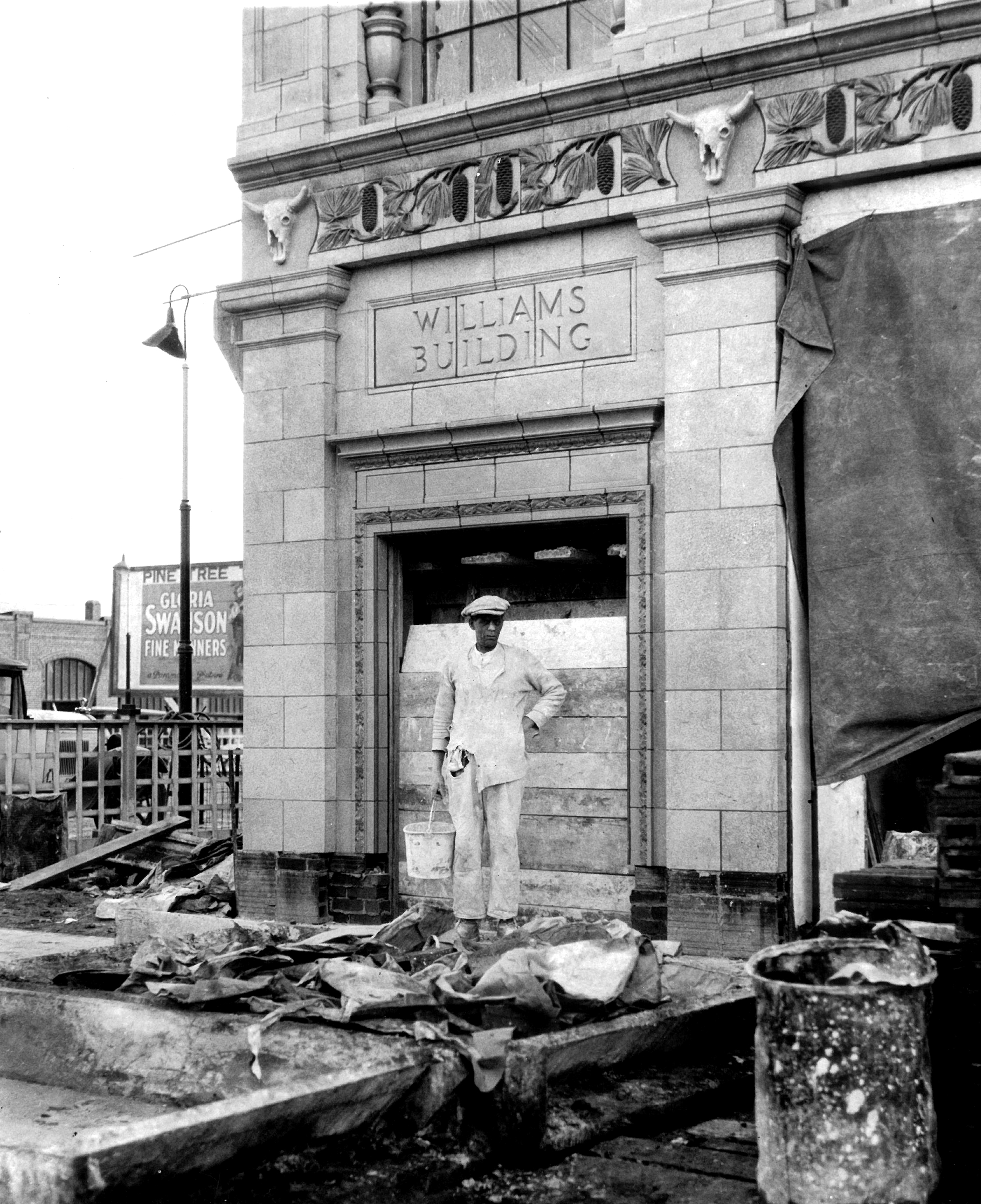

![]()

Williams Building, Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi015944, photo file 618b

-

![]()

White Pelican Hotel, Klamath Falls.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 988D057, photo file 618b

Related Entries

-

![Chris Eyre (1968-)]()

Chris Eyre (1968-)

Chris Eyre, the nation's most celebrated American Indian film director,…

-

![Crisis in the Klamath Basin (documentary film)]()

Crisis in the Klamath Basin (documentary film)

The 1958 KGW-TV documentary Crisis in the Klamath Basin broke important…

-

![Danny Miles (1945–)]()

Danny Miles (1945–)

Daniel Joseph Miles was head coach of the men’s basketball team at the …

-

![Endangered Klamath suckers]()

Endangered Klamath suckers

Since Lost River suckers (Deltistes luxatus) and shortnose suckers (Cha…

-

![Harry Dolan Boivin (1904–1999)]()

Harry Dolan Boivin (1904–1999)

Harry Boivin, a legislator from Klamath County, rose to prominence duri…

-

![Houston Opera House]()

Houston Opera House

The story of the Houston Opera House begins with the arrival of John…

-

![James Ivory (1928-)]()

James Ivory (1928-)

James Ivory, who received three Academy Award nominations for best dire…

-

![Jehovah's Witnesses Riots, 1942]()

Jehovah's Witnesses Riots, 1942

On Sunday, September 20, 1942, nearly a thousand residents of Klamath F…

-

![Klamath Basin Project (1906)]()

Klamath Basin Project (1906)

When trapper Peter Skene Ogden first saw the Upper Klamath River Basin …

-

![Klamath Falls streetcar system]()

Klamath Falls streetcar system

In 1906, two companies were granted street railway franchises in Klamat…

-

![Klamath River]()

Klamath River

The Klamath River originates on a plateau east of the Cascade Range in …

-

![Lower Klamath Lake]()

Lower Klamath Lake

Before human engineering altered the upper Klamath Basin, water flowed …

-

![Maud Baldwin (1878-1926)]()

Maud Baldwin (1878-1926)

Maud Baldwin was born in Linkville (now Klamath Falls) on August 8, 187…

-

![Oregon Institute of Technology (Oregon Tech)]()

Oregon Institute of Technology (Oregon Tech)

The Oregon Institute of Technology (OIT, also now known as Oregon Tech)…

-

![Richard L. Wendt (1931-2010)]()

Richard L. Wendt (1931-2010)

Richard L. Wendt, of Klamath Falls, was a founder of JELD-WEN, Inc., on…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Sisemore, Linsy. History of Klamath County, Oregon: Its Resources and Its People. Klamath Falls, Ore.: 1941.

Yates, Richard “Oregon Voices: Klamath Falls Goes to War: A Personal and Newspaper Reminiscence.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 107.3 (Fall, 2006): 410-423.

Brown, Brian. "Klamath Falls Geothermal District Heathing Systems." GHC Bulletin (March 1999).

Klamath Echoes.16 Volumes. Klamath County Historical Society, 1964-1979.

“Destruction of the Business Part of Linkville.” Portland Oregonian, September 7, 1889.

Kiniry, Laura. "The 15 Best Small Towns to Visit in 2023." Smithsonian Magazine, June 6, 2023.