Reflecting on Meriwether Lewis after his death, Thomas Jefferson bemoaned the loss to “his country of one of her most valued citizens whose valour & intelligence would have been now imployed.” Lewis had taken his own life on October 11, 1809, along the Natchez Trace at Grinder’s Inn on his way from the lower Mississippi Valley to Washington, D.C. For many, his death came as a shock and surprise, but Lewis had long been vulnerable to what friends called “melancholy” and what Jefferson described as “hypochondriac affections.” He also had been under a cloud of congressional suspicion over his management of federal funds in Louisiana Territory, charges that had prompted his trip to Washington. Nonetheless, Lewis was a national hero for his leadership of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and his political future seemed assured. Some historians have argued that his failure to finish writing up the expedition journals also weighed on him. When the official Journals finally appeared in 1814, they created the nation’s first detailed image of the Oregon Country.

Meriwether Lewis was born on August 18, 1774, near Charlottesville in Albemarle County, Virginia. He was educated in a Latin school as a teenager and served as a volunteer at age twenty in the new federal government’s forceful suppression of tax evaders. Joining the regular army in 1795, Lewis served on the western frontier under his future expedition co-leader William Clark in 1796 and was promoted to lieutenant in 1799. During his service, he drew attention for his marksmanship, diligence under command, and perseverance in the face of challenges.

President Thomas Jefferson had known Lewis’s father as a neighbor and army officer (he was felled during the Revolutionary War), and he took an interest in the young officer’s steady rise in the army. In February 1801, he asked Lewis to serve as his personal secretary, or aide-de camp, rather than pursue an army command. Lewis readily accepted, even though Jefferson warned that he would be paid poorly, “only 500 D. which would scarcely be more than an equivalent for your pay & rations.”

Lewis was promoted to captain in March 1801, and his first duty as the president’s secretary was evaluating army officers for a planned reduction of the armed forces. But it was another task that would define his life—leadership of Jefferson’s long-planned expedition to western North America. As a teenager in 1793, Lewis had offered to join an expedition that French scientist André Michaux had been selected to lead. While that plan and others had frustratingly eluded Jefferson’s best efforts, in January 1803 the president persuaded Congress to approve and fund what would become known as the Corps of Discovery.

In 1803, Jefferson put Lewis to work preparing for the expedition, sending him to scientists and technicians in Lancaster and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, for advice and training in navigation, medicine, and armaments. Lewis recruited William Clark, his elder by four years, to share leadership, and the two of them selected members of the expedition and organized its start at Wood River, near present-day St. Louis.

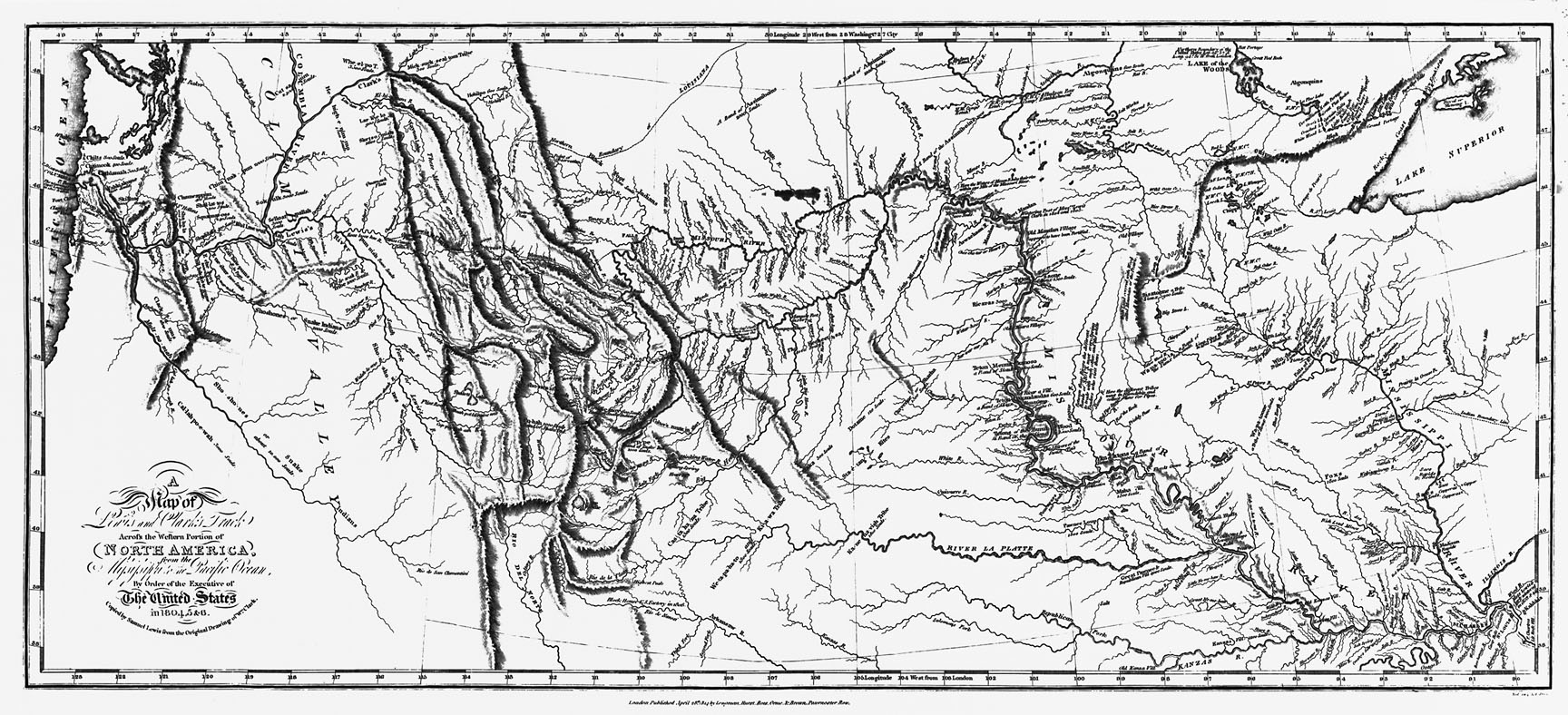

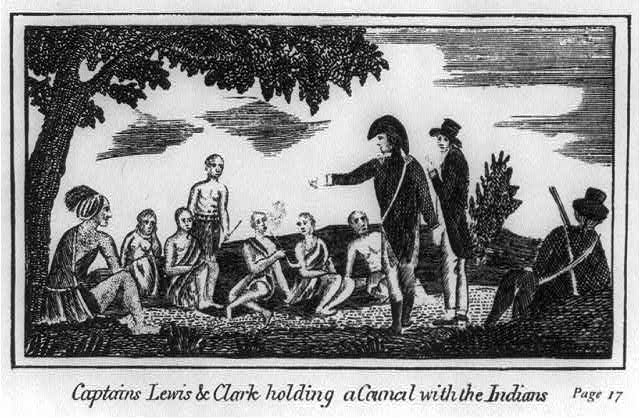

For twenty-eight-months, from May 1804 to September 1806, the thirty-three members of the Corps journeyed up the Missouri River by boat and canoe, across the Rocky Mountains by horse and on foot, down the Columbia River by log canoe to the Pacific, and finally back to the United States. The expedition was remarkable for losing only one member (to illness), having minimal conflicts with Native groups (two Indians killed), producing hundreds of maps, and keeping the official Journals of the trip—more than a million words that include descriptions and commentaries on people, flora, fauna, and landscape. The expedition’s purpose was primarily scientific, but Jefferson also instructed Lewis to pay attention to potential trade, valuable natural resources, and political relations with other nations’ claims to territory in the West.

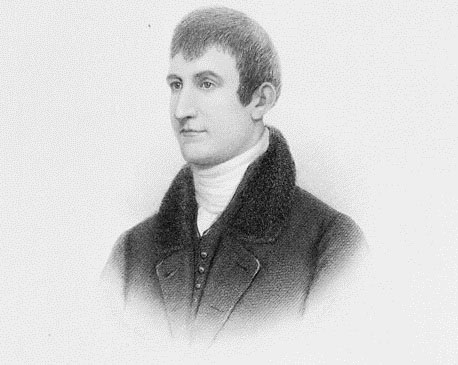

Throughout the expedition, Lewis demonstrated remarkable leadership. On the return from the Pacific, however, his attitude toward Native people became less forgiving, and conflicts with Indians threatened to damage the Expedition. Nevertheless, on his return home, Lewis embraced his experience in the West, including clothing himself in a fur tippet cloak given him by a Lemhi chief in present-day Idaho for artist Charles Saint-Mémin’s portrait of him as a heroic frontier explorer.

Lewis’s tenure as governor of Louisiana Territory included managing fur traders’ access to Indian villages, overseeing U.S. military operations, and enforcing policies meant to secure American control of the vast Missouri River region. But his executive management came under criticism by his territorial secretary, Frederick Bates, and Secretary of War William Eustis in Washington, D.C. Bates commented on Lewis’s condition on July 25, 1809: “Our Gov. Lewis, with the best intentions in the world, is, I am fearful, losing ground….He has talked for this 12 Mos. of leaving the country—Every body thinks now that he will positively go, in a few weeks.”

His death by his own hand on Natchez Trace has long been questioned. Some have argued that Lewis was murdered by unknown assailants, perhaps robbers; but nearly all historians who have weighed the evidence conclude that he committed suicide. Why he took his life remains a contested issue, with causes ranging from derangement caused by syphilis to cognitive imbalance from lingering malaria to the effects of a bipolar mental disorder. Meriwether Lewis’s grave and a memorial obelisk are located on Natchez Trace near the site of Grinder’s Stand in Lewis County, Tennessee.

-

![Lewis and Clark, "Track Across the Western Portion of North America, " published in 1814.]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition map.

Lewis and Clark, "Track Across the Western Portion of North America, " published in 1814. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, CN054377

-

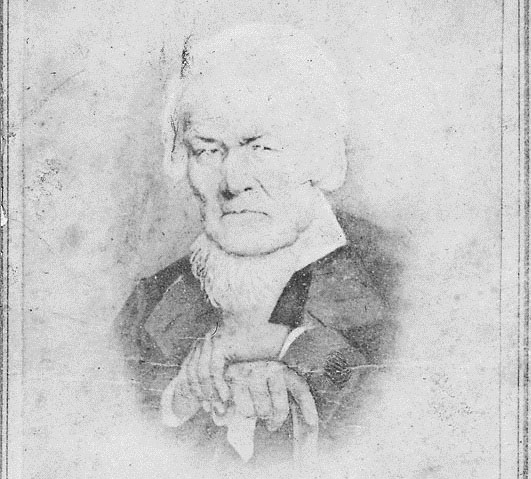

![Captain Meriwether Lewis, 1807]()

Captain Meriwether Lewis, 1807.

Captain Meriwether Lewis, 1807 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., by Charles Willson Peale, OrHi9739

-

![Lewis's branding iron]()

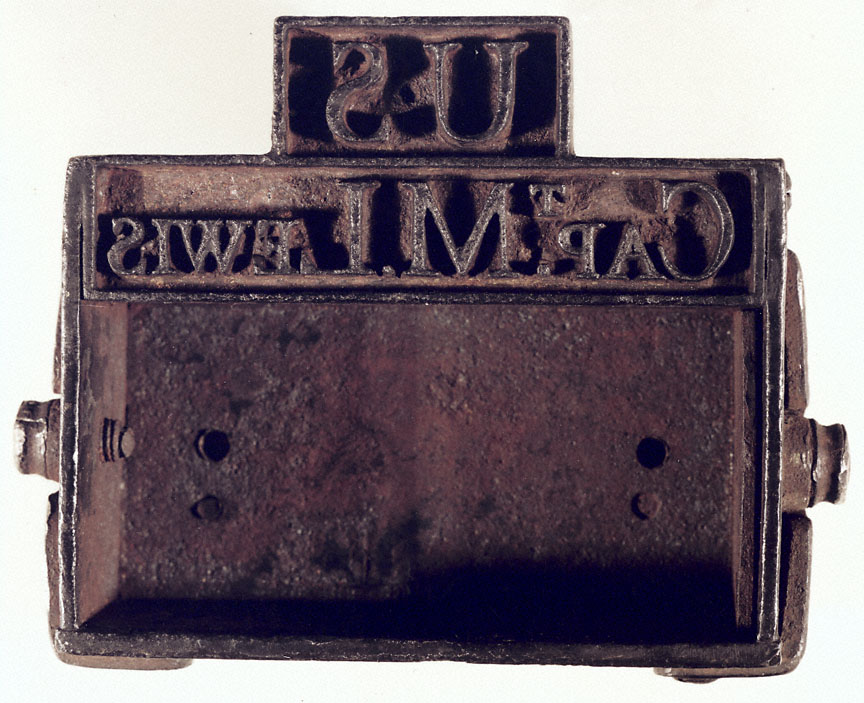

Lewis's branding iron.

Lewis's branding iron Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi104345

-

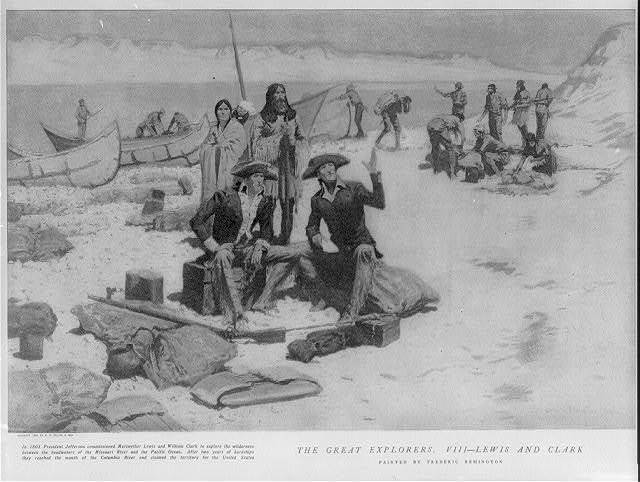

!["Captain Lewis and Clark holding a council with the Indians," from the Gass journals, 1810]()

"Captain Lewis and Clark holding a council with the Indians," from the Gass journals, 1810.

"Captain Lewis and Clark holding a council with the Indians," from the Gass journals, 1810 Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-17372

Related Entries

-

![Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)]()

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau is remembered primarily as the son of Sacagaw…

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Patrick Gass (1771-1870)]()

Patrick Gass (1771-1870)

Patrick Gass was one of the early enlistees in the expeditionary force …

-

![Sacagawea]()

Sacagawea

Sacagawea was a member of the Agaideka (Lemhi) Shoshone, who lived in t…

-

![Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- c. 1839-1843)]()

Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- c. 1839-1843)

Toussaint Charbonneau played a brief role in Oregon’s past as par…

-

![William Clark (1770-1838)]()

William Clark (1770-1838)

William Clark is indelibly connected to Oregon in many ways, some obvio…

-

![York (ca. 1770–?)]()

York (ca. 1770–?)

York was William Clark's slave and an integral member of the Lewis and …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Jackson, Donald, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Second Edition. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1978.

Danisi, Thomas C. and John C. Jackson. Meriwether Lewis. Amherst, NY: Promethus Books, 2009.

Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.