Ranald MacDonald (Clatsop Chinook) was a navigator, whaler, tutor, interpreter, and writer. In 1848-1849, he was the first native speaker of English to teach that language in Japan, which had been closed to foreigners for two centuries before he arrived. He also reportedly wrote the first report to Congress by an Indian from Oregon.

He was born at Fort George in present-day Astoria on February 3, 1824. His father, Archibald McDonald, was an officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company (McDonald’s children adhered to the original Scots spelling of the family name, MacDonald). His mother, Koale’xoa—also known as Princess Raven—was the youngest daughter of Concomly (Comcomly), a powerful Clatsop Chinook leader on the lower Columbia River. Koale’xoa died soon after Ranald’s birth, and within two years his father married Jane Klyne, who was German and Swiss. He “was placed under her care,” MacDonald wrote in his autobiography, “at an age so young that I took her as my veritable mother.” Educated at home and then at schools in Fort Vancouver and Winnipeg, Manitoba, MacDonald was apprenticed to a bank in Upper Canada when he was about eighteen years old. In 1838, he apprenticed with fur-trade banker Edward Ermatinger in St. Thomas.

But he found banking lacking as a profession and resolved to study Japanese and, “if occasion should offer, to instruct them of us.” There may have been reasons other than youthful boredom that sparked MacDonald’s first trip to Japan. He wrote in his autobiography that he had learned about his mixed-race heritage by accident, when a romance had failed due to prejudice against Indians, and he apparently believed that the Japanese were ancestors of North American Indians.

MacDonald left his job at the bank in 1845 and spent several years as a navigator and harpooner on a New England whaling vessel. By prearrangement with the captain of the whaler, in 1848 he left the ship in a small boat when it was near Rishiri Island, in northern Japan, and rowed toward land. MacDonald was twenty-four years old, and Japan had been isolated for two hundred years. He reached Japan during the Edo Period, when the shogun had banned foreign travel and trade, except for limited trade relations with China and the Netherlands in the port of Nagasaki.

When MacDonald reached Rishiri Island, the resident Ainu captured him. His explanation that he was shipwrecked and had peaceful intentions was accepted, and he was placed under house arrest rather than killed. He was eventually transported, sometimes on a junk, to the seat of government in Nagasaki, about a thousand miles by sea from where he had first landed. MacDonald’s arrival in Nagasaki was timely. The Tokugawa Shogunate, the feudal military government that ruled the country, needed trained interpreters in English. For seven months, MacDonald was a tutor for fourteen Japanese interpreters, primarily teaching them English conversation and pronunciation.

In April 1849, ten months after MacDonald had landed in Japan, the USS Preble arrived to liberate thirteen U.S. seamen who had been shipwrecked and imprisoned in the country. MacDonald joined the liberated group and left Japan with them. Of the Japanese student-interpreters, he later wrote: “the dearest to me in every regard, and most esteemed, and ever loved” was Murayama Yeannoske (Einosuke Moriyama). In 1854, Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy’s East Indies Squadron arrived in Japan to demand that the Shogunate open its door to America; Moriyama was a chief interpreter on behalf of the Japanese.

MacDonald is recognized by many Japanese as Japan’s first English teacher. He later wrote that he had purposefully traveled to Japan, where “a gentle kindness…pervaded their general regard and treatment of me.” After leaving Japan, MacDonald worked as a gold miner and rancher in Australia and Canada before returning to the United States. He never married.

MacDonald wrote his account of his adventures in Japan: Story of Adventure of Ranald MacDonald, first teacher of English in Japan, A.D. 1848–49, which details Japanese laws, foodstuffs, dress, geography, and customs. It also provides physical details of his Japanese pupils and his manner of teaching them. He completed several drafts of the manuscript, but the book was not published until 1923.

MacDonald died on August 24, 1894, and is buried in the Ranald MacDonald Cemetery in Ferry County, Washington. There are also monuments to him in Nagasaki (1964), on Rishiri Island (1987), and in Astoria (1988). The Friends of MacDonald Society was formed in 1988 and now has over two hundred members.

-

![]()

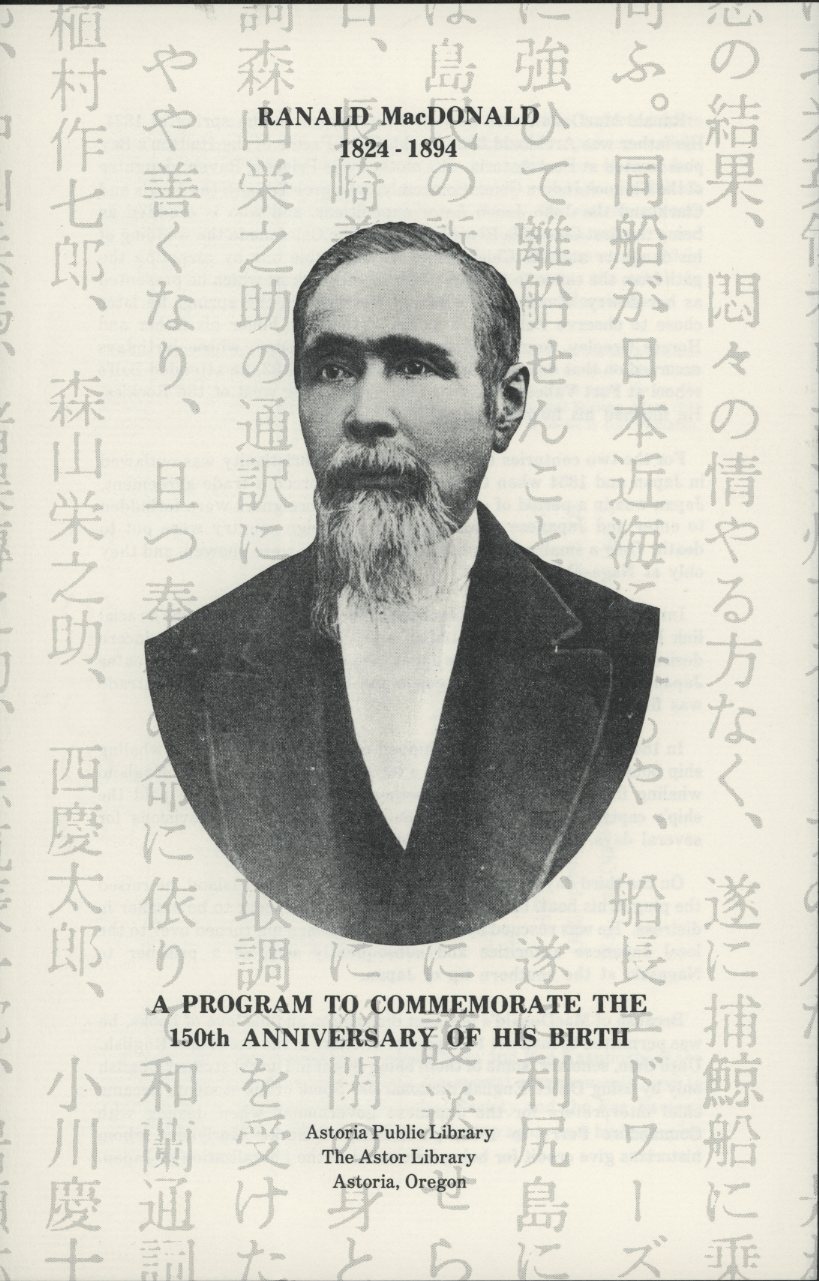

Ranald MacDonald commemorative program, Astoria Public Library, 1974.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Ranald MacDonald vertical file

Related Entries

-

![Concomly (1765?-1830?)]()

Concomly (1765?-1830?)

Of the several Chinook men called Concomly at one time or another, the …

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lewis, William S. and Murakami, Naojiro, ed. Ranald MacDonald: The Narrative of his early life on the Columbia under the Hudson's Bay Company's regime; of his experiences in the Pacific Whale Fishery; and of his great Adventure to Japan; with a sketch of his later life on the Western Frontier, 1824-1894. Portland: The Oregon Historical Society, 1993. This is a reprint of the 1923 edition, with new foreword and afterword.

Schodt, Frederik L. Native American in the Land of the Shogun: Ranald MacDonald and the Opening of Japan. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press, 2003.

Roe, Jo Anne. Ranald MacDonald: Pacific Rim Adventurer. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1997.