By early May 1938, as his reelection bid faltered in the primary, Charles Henry Martin, Oregon’s anti-New Deal governor, placed the blame for his failing fortunes on his nemesis: a vicious communist conspiracy. If there was any blame, it was better placed thousands of miles from Moscow, in Washington, D.C. Martin had attracted the enmity of many inside the Roosevelt administration, most prominently Harold Ickes, Frances Perkins, Harry Hopkins, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself.

The third of Samuel H. and Mary Jane Martin’s ten children, Charles Henry Martin was born in Grayville, Illinois, on October 1, 1863. After the death of his two older brothers, he reluctantly accepted the mantle of service to his country at the demand of his stubborn and determined father. Accepted at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, expelled after two years, and then readmitted, Martin graduated as a second lieutenant in June 1887. He joined the Fourteenth “Fightin’ Irish” Infantry, his father’s Mexican War regiment, and took up the first assignment of his forty-year military career at Vancouver Barracks in Washington State. He married Louise Jane Hughes, the daughter of Ellis G. Hughes, one of Portland’s leading attorneys, on April 15, 1897.

Martin overcame the inevitable stagnation of his military career at Vancouver Barracks by demanding that the army assign him to the war in the Philippines, which began in 1898. After displaying heroic actions in the Boxer Uprising in 1900, he rose steadily through the officer ranks. In the closing months of World War I, military leaders, who wanted Black troops out of Europe, assigned General Martin command of the segregated, all-Black 92nd Division to “eradicate any notions of equality [the Black soldiers] may have picked up in France.” Martin—now known as “Iron Pants,” a nickname bestowed on him by enlisted trainees at Camp Grant, Illinois—referred to his command as the “rapist division.” He used his position to break the spirit of Black soldiers, whom he declared were "not by any means equal to the average white man." Major General Martin ended his military career in 1927, retiring after serving for two years as the commander of U.S. forces in Panama overseeing the Panama Canal.

Charles Henry and Louise Martin retired to Portland, where the couple had significant real estate holdings inherited from Louise’s parents, including the Hughes Building. Moving easily among Portland’s ruling elite, Martin parlayed his military reputation, business activities, and participation in civic affairs into election as a Democrat to represent Oregon’s Third Congressional District in 1930.

With the country mired in the Depression, Martin became identified in Congress with insurgent Democratic conservatives who acted as an independent voting bloc in the factionalized Democratic-controlled House. During his first term, he consistently voted against bills designed to provide relief to the unemployed. Reelected in the Roosevelt landslide in 1932 but inexplicably absent during the “one-hundred days” legislative period in 1933, Martin concluded his congressional career with his most lasting legacy to Oregon and the Northwest by playing an important role in persuading FDR to fund the construction of Bonneville Dam.

Although Martin campaigned in the 1934 gubernatorial election as a champion of the New Deal, after he was elected governor he conducted an unrelenting attack on most New Deal programs. His disdain for relief and welfare policies, which he claimed “coddled communists,” reached its apogee when he supported a plan to chloroform wards of the state by “putting 900 of the 969 inmates at the Fairview Home in Salem ‘out of their misery’” to balance the state budget. “I am a Democrat,” he said, “but not a New Dealer.”

Convinced that he was under assault by a vast communist conspiracy composed of the unemployed, organized labor, and New Dealers, Martin assigned Oregon state policemen to spy on his political opponents (including members of the state legislature) and infiltrate opposition movements. He then launched a secret “Red Hunt” for “Jew Communists” and “shanty Irishmen.” Repudiated in his bid for reelection, and embittered by FDR’s supposed betrayal, Martin spent the final years of his life in a crusade against the president. He died on September 22, 1946.

-

![Gov. Charles Martin, c. 1934]()

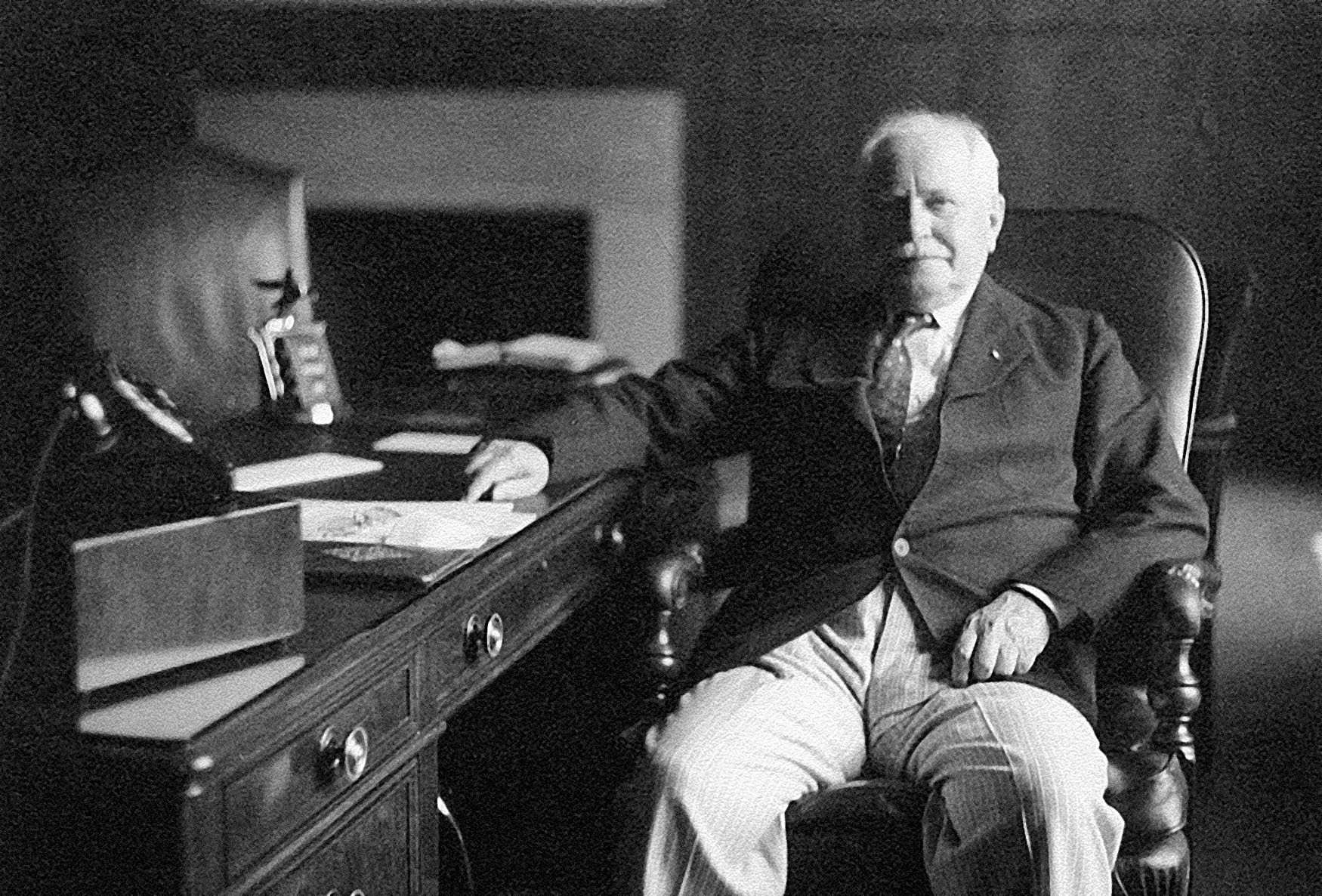

Charles Martin.

Gov. Charles Martin, c. 1934 Ore. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., cn004880

Related Entries

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

MacColl, E. Kimbark. The Growth of a City: Power and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1915 to 1950. Portland, Ore.: Georgian Press Company, 1979.

Murrell, Gary. "Perfection of Means, Confusion of Goals: The Military Career of Charles Henry Martin." PhD Diss., University of Oregon, 1994.

Murrell, Gary. Iron Pants: Oregon's Anti-New Deal Governor, Charles Henry Martin. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 2000.