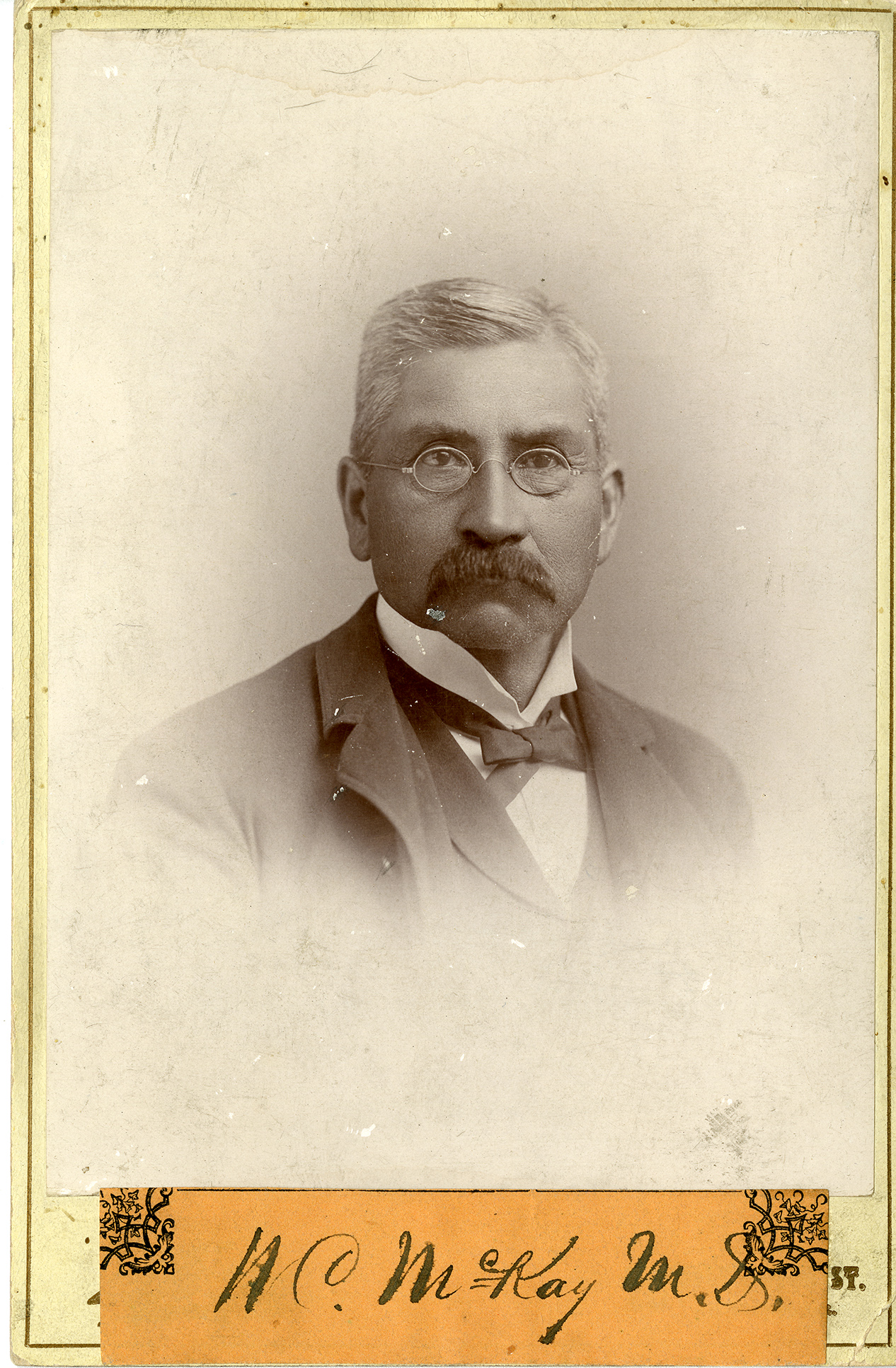

Dr. William Cameron McKay [mə kī´] lived his entire life on the lower and middle Columbia River, save for five years spent pursuing an education in the eastern United States. He experienced at first hand the seismic historical transition of the region, from one dominated by its first people to one ruled by EuroAmerican newcomers.

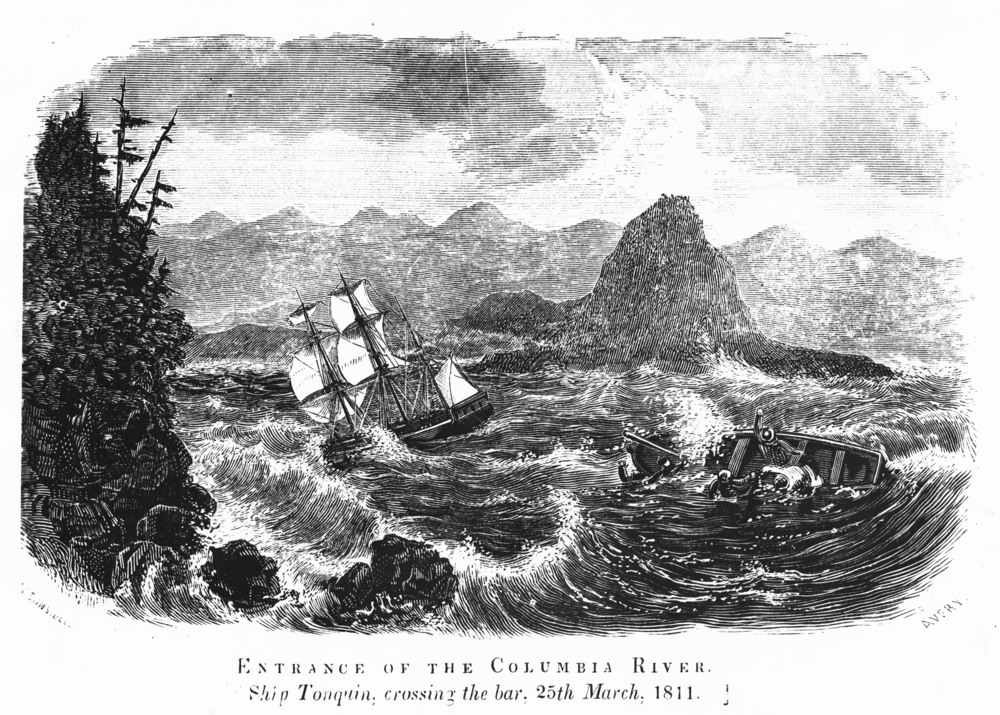

McKay was born at Astoria (then named Fort George) in 1824. His father was Thomas McKay, the Scottish-Ojibwa fur company employee whose own father was among those killed in the disastrous trading foray of the ship Tonquin to Vancouver Island in 1811. His mother was a Lower Chinook from the family of Concomly, then a principal chief on the lower Columbia River. Their union was one of a number of like examples of what was sometimes called “princess diplomacy,” which was intended to secure good relations between a chief’s people and foreign newcomers. She died when McKay was a small child.

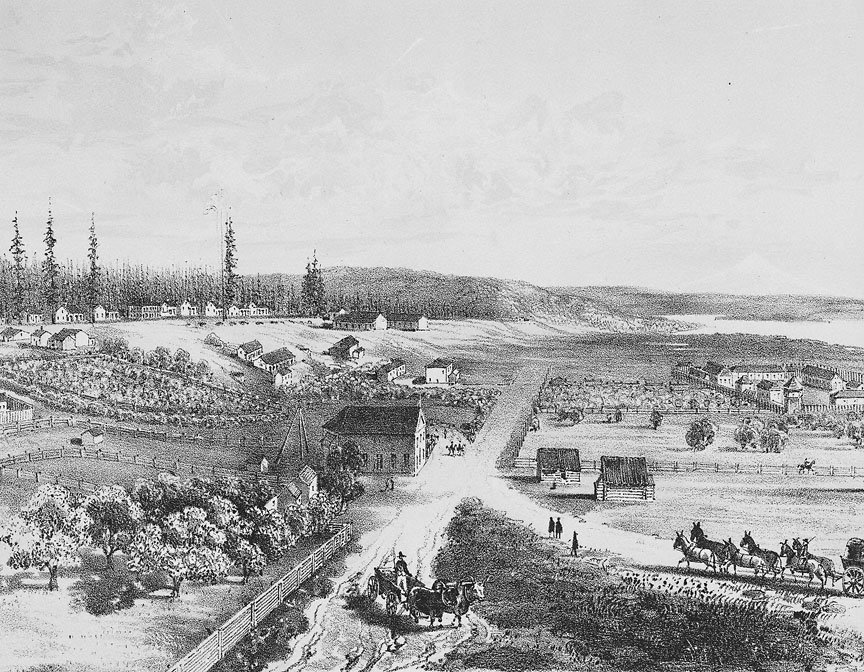

Shortly after William McKay was born, his father moved the family to Fort Vancouver, which had been established in 1825. Thomas McKay's mother, Marguerite Waddens McKay, had remarried following the Tonquin disaster. Her husband, now young Billy's step-grandfather, was Dr. John McLoughlin, chief factor of Hudson’s Bay Company operations at the new fort.

Thomas McKay intended to send his son to Scotland for further education but was persuaded by missionary Marcus Whitman to send him to a United States school instead. At age fourteen, Billy McKay departed for the East, where he first studied at Fairfield Academy in New York and at Wilbraham Academy in Massachusetts. He subsequently pursued a course of medical studies at Geneva College, New York; Castleton Medical College, Vermont; and Willoughby Medical College, Ohio. He returned to the lower Columbia with the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 1843 overland express. Owing to his young age, he was granted a license to practice medicine, but not a medical diploma.

McKay subsequently married and entered the mercantile business in Oregon City. His wife Catherine and an infant son died in 1848. The following year, he left for California in the company of McLoughlin’s son David to try his luck in the gold fields. The two returned—luckless—within the year.

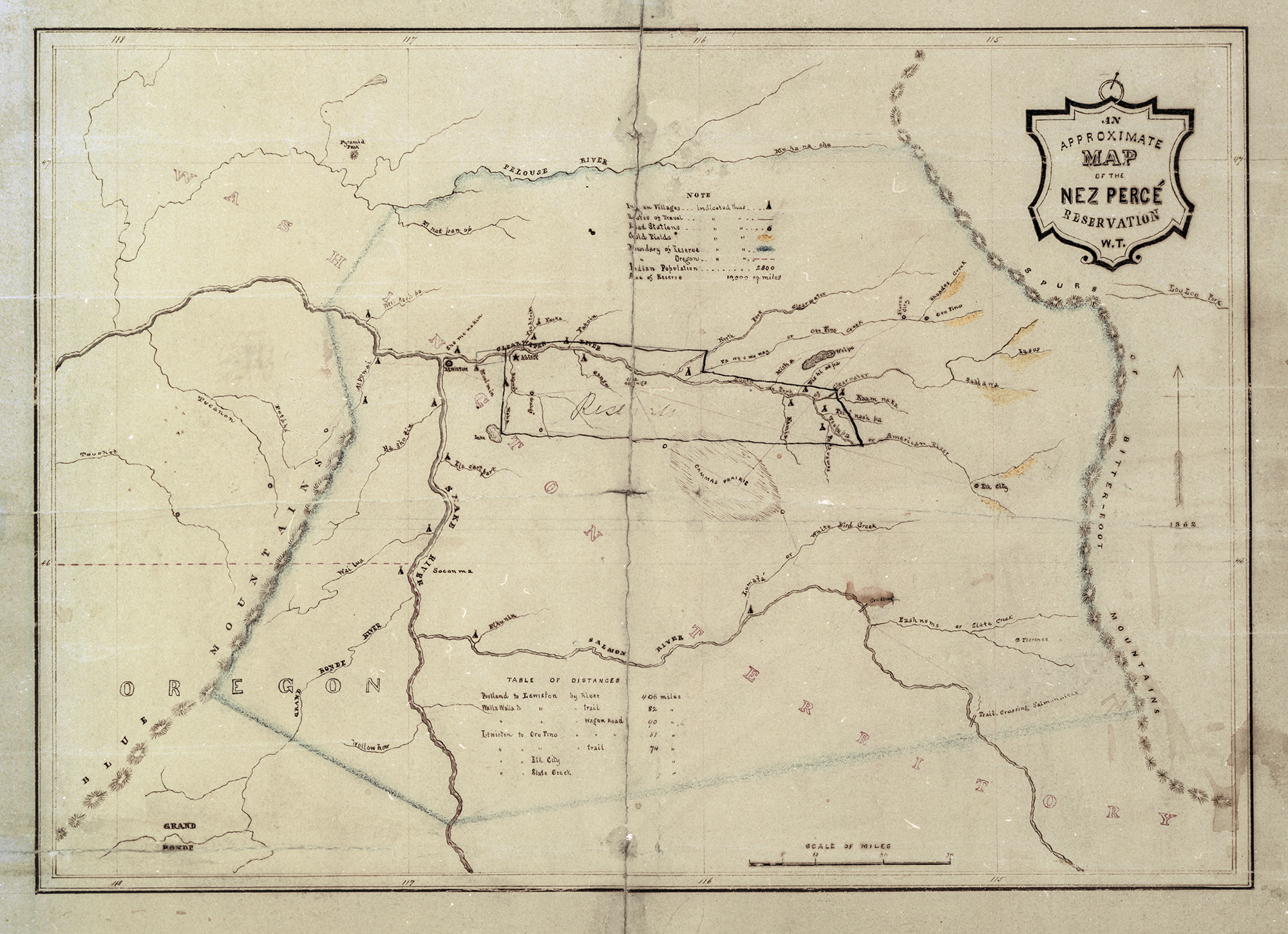

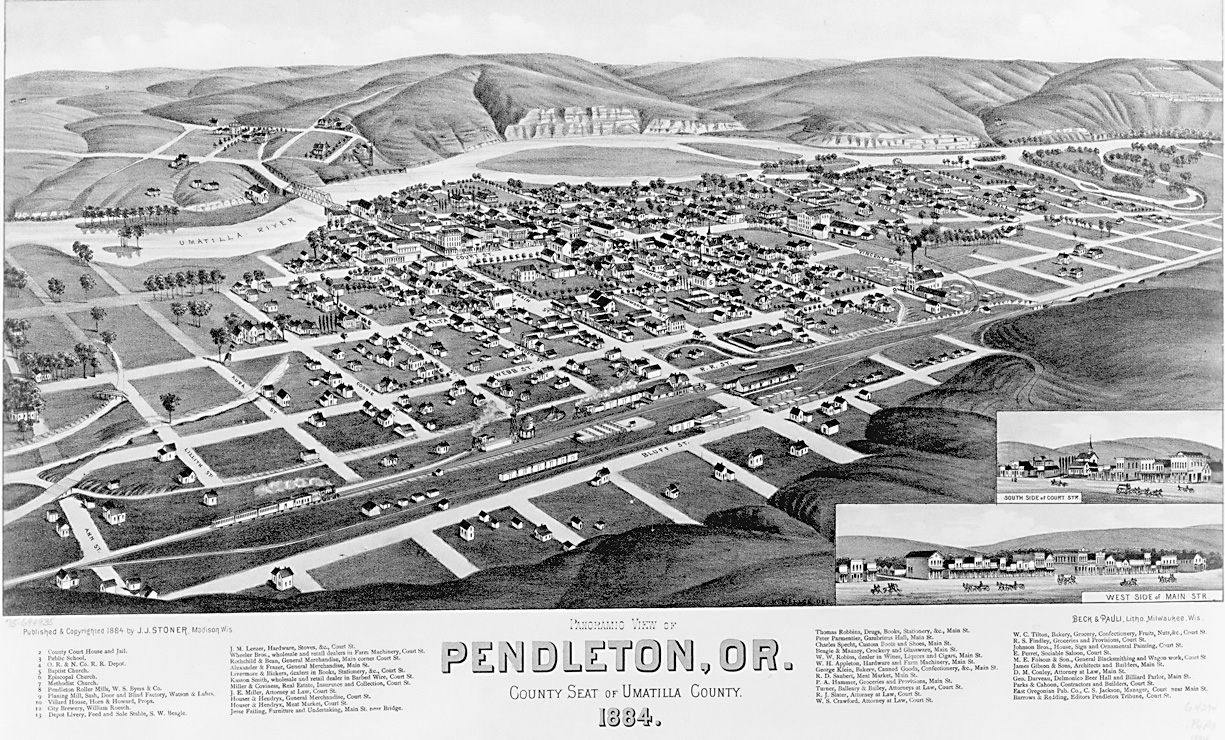

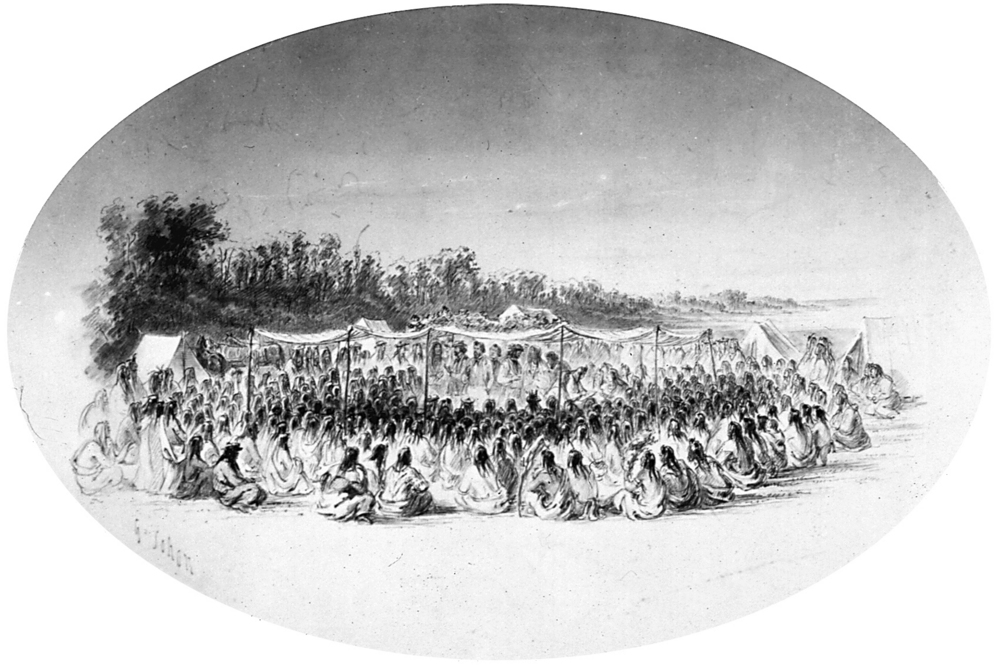

In 1852, McKay applied his mercantile experience to a new venture and established a trading post at present-day McKay Creek (near modern Pendleton). His business involved daily interactions with Natives, and he was recruited to serve on government commissions charged with negotiating treaties with middle Columbia tribes. While involved in treaty negotiations at Fort Walla Walla in 1855, McKay began courting Margaret Campbell, the part-Cree sister-in-law of the local Hudson’s Bay Company chief. The two were married at The Dalles in 1856.

Many of those who signed the treaties that McKay had helped to negotiate were unhappy with the results, and McKay himself faulted the government for its heavy-handed attempt to force compliance. As secretary of the treaty commissions, McKay had been instrumental in persuading tribal leaders to affix their marks to the treaties, although he himself recognized that none of them had an accurate conception of "the Power and force of his mark on a Paper." While he attributed the destruction of his trading post by Indians during the subsequent Yakama War to his role on the treaty commissions, his accounts of the treaties and the war reveal considerable sympathy for the Native side.

No resulting animosity seems to have affected his relationship with people of the Warm Springs Reservation, where McKay was appointed agency physician in 1861. That community had been suffering losses of property and life at the hands of marauding Paiutes for some years, and many of its men signed up to serve as scouts in the U.S. Army’s 1866–1867 campaign against the Paiutes. The scouts were divided into two units, one under Dr. McKay’s command. By all accounts, the Warm Springs scouts were the army’s most effective and fearsome fighting force in that campaign.

After the war, Alfred B. Meacham, superintendent of Indian Affairs in Oregon, delegated Dr. McKay to find and recover Native captives who had been forced into slavery and were living among tribes of the region. In addition to Paiutes captured during the Paiute War, these included southern Oregon and northern California victims of Indigenous slave raiders. With his half-brother Donald McKay serving as an interpreter, Dr. McKay and his party covered a good part of eastern Oregon and southeastern Washington in pursuit of the captives. Dr. McKay was again offered command of the Warm Springs scouts during the Modoc War of 1873, but he declined. Donald McKay served instead, winning considerable renown for his role in that conflict.

Dr. McKay spent his later years as agency physician at the Umatilla Reservation. While not an enrolled member of any of that reservation's founding tribes, he was eventually granted the formal adoption that entitled him to an allotment of Indian land under provisions of the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887. He also maintained a private medical practice in Pendleton and served for a time as county coroner.

Owing to his Native heritage, Dr. McKay was denied the franchise during the 1870 general election. U.S. District Judge Matthew P. Deady rejected his suit to win back that right, but Dr. McKay marshaled the support of a number of prominent men—including President Ulysses S. Grant, whom he had befriended when Grant was a young officer at Fort Vancouver during the 1850s. That indignity was reversed in 1872 by a special act of Congress.

In 1872, Willamette University College of Medicine awarded Dr. McKay an honorary medical diploma, thus recognizing his status as one of Oregon's early physicians. His many contacts with influential men of the time notwithstanding, he was unable to secure compensation from the U.S. government for the loss of his trading post, and his other ventures to win financial security beyond his meager salary as a civil servant never bore fruit.

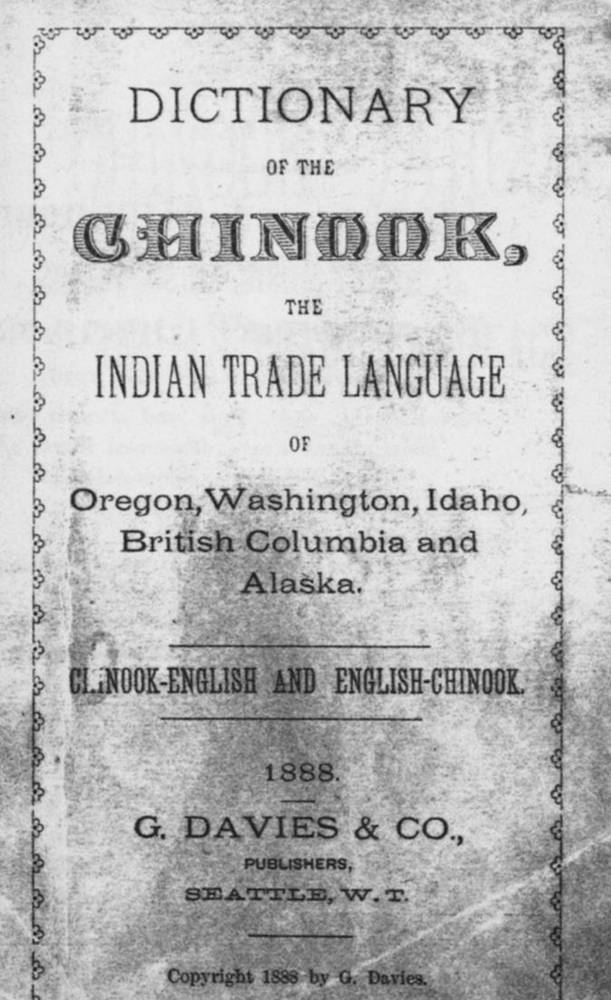

Dr. McKay corresponded with writers and historians who recognized his connection to the formative events of modern Pacific Northwest history. His participation in the grand celebration held at Astoria in May 1892, marking the centennial of the American presence on the Columbia River, is commemorated in his “Chinook Address,” composed entirely in Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa).

Dr. McKay died of heart failure at his home on January 2, 1893. He was buried in the Olney Cemetery in Pendleton and was survived by his wife, two sons, a daughter, and two grandchildren.

-

![]()

Dr. William Cameron McKay.

Courtesy OHSU Historical Collections & Archives

-

![]()

Margaret Campbell McKay.

Courtesy OHSU Historical Collections & Archives

Related Entries

-

![Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)]()

Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)

According to our best information, the name "Chinook" (pronounced with …

-

![Concomly (1765?-1830?)]()

Concomly (1765?-1830?)

Of the several Chinook men called Concomly at one time or another, the …

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Pendleton]()

Pendleton

Pendleton, a city of 17,107 in the 2020 census, sits in the foothills o…

-

![Tonquin (ship)]()

Tonquin (ship)

The Tonquin, built in 1807, was described by Edmund Fanning, its builde…

-

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Clark, Keith, and Donna Clark. "William McKay's Journal, 1866-67: Indian Scouts." Oregon Historical Quarterly 79 (Summer 1978): 121–171; (Fall 1978): 269–333.

"Dr. W. C. McKay." East Oregonian (Pendleton), January 2, 1889.

Hyde, Anne F. Empires, Nations, and Families: A History of the North American West, 1800–1860. Norman: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Keane, Roger H. Dr. William Cameron McKay: the First Man Born in the Oregon Country to Become a Doctor. University of Oregon Medical School Medical History Club, 1933. Box 88, OHSU Historical Collections and Archives, Oregon Health

Lockley, Fred. “Fred Lockley writes about Dr. William C. McKay.” Oregon Journal, September 19, 1943.

Sciences University, Portland.

McKay, Leila. Interview by Fred Lockley. Oregon Journal, October 21, 1927.

McKay, William C. Papers, Mss. 413, Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland.

Simpson, Louis. “A Personal Narrative of the Paiute War.” In Wishram Texts, by Edward Sapir, 204–227. Leyden: E. J. Brill., 1909.

Zenk, Henry. "'Dr. McKay's Chinook Address May 11 1892': A Commemoration in Chinook Jargon of the First Columbia River Centennial." In Great River of the West: Essays on the Columbia River, edited by William L. Lang and Robert C. Carriker, 35–52. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.