The Modoc are a thriving Indigenous people who live predominantly in northeastern California, south-central Oregon, and northeastern Oklahoma. Many individuals of Modoc ancestry are citizens of the Klamath Tribes, a federally recognized Indian nation, and the Modoc Nation, the smallest federally recognized tribe in Oklahoma. Individuals of Modoc ancestry are also citizens of many other Indigenous nations, the states in which they reside, and the United States.

Most Modoc living in Oklahoma today are descendants of the followers of Kintpuash (Strikes the Water Brashly), also known as Captain Jack. Those people were imprisoned following the 1872–1873 Modoc War and sent as punishment to live on the Quapaw Indian Reservation as part of a process known as Indian removal. In 1909, the United States government passed legislation permitting the Modoc of Oklahoma to return to Oregon and take up residence on the Klamath Reservation. Some, but not all, did.

The Modoc in Oregon along with the Klamath and the Yahooskin, who make up the confederated Klamath Tribes, were subjected to the Klamath Termination Act of 1954, which ended the federal supervision of tribal lands and federal aid and otherwise sought to end the special relationship between the Klamath Tribes and the federal government. The 1954 act also terminated relations between the federal government and the Modoc Nation of Oklahoma, though federal relations with the tribe had ceased decades earlier. Termination was, by any measure, a failure for the Modoc people. In 1978, the federal government re-acknowledged the inherent sovereignty of the Modoc Nation of Oklahoma. Eight years later, in 1986, Congress did the same for the Klamath Tribes.

In the twenty-first century, the Modoc of Oregon, Oklahoma, and California are thriving and their populations are growing. As of 2024, approximately 200 Modoc lived in Oklahoma and about 600 lived in Oregon. A number of tribally operated businesses, including the Kla-Mo-Ya Casino in Chiloquin, Oregon (jointly operated by the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin as part of the Klamath Tribes), and the Modoc Market and the Stables Casino in Miami, Oklahoma (operated by the Modoc Nation of Oklahoma), contribute to their local economies and support governance and investment for tribal benefit.

Traditional Culture

The Modoc’s name for themselves is maklaks, meaning people or community. The Klamath, who spoke a closely related dialect of the same Lutuamian language, referred to the Modoc as moatokni maklaks or “people of the south.” Their ancestral homeland was the Klamath and Tule Lakes region, stretching from the Lost River south to Mount Shasta. Indigenous population estimates before EuroAmerican contact are difficult to determine accurately, but anthropologists estimate that between 400 to 1,000 Klamath and Modoc lived in the region in the late 1700s; anthropologists Alfred Kroeber and Theodore Stern agree that their population was about 500 in 1770. The earliest documented evidence of Modoc people in the Klamath Basin is in the form of rock art estimated to be 6,500 years old.

Before the nineteenth century, when EuroAmericans entered the region and began establishing settlements, the Modoc lived a material life similar to other Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau. They caught and processed large amounts of fish such as salmon and the vitally important Lost River sucker, known as c’waam in the Modoc language. They hunted deer, elk, and ducks and other waterfowl, and they annually gathered seeds, roots, and berries at specially chosen horticultural sites that were cared for and managed for generations.

The Modoc lived in autonomous villages, each with its own spiritual and civic leaders, and over millennia developed a dynamic social world accustomed to their semi-sedentary lifestyle and well-suited to the environment of the Klamath Basin. During the cold, snowy winters, the Modoc lived in semi-subterranean earth lodges that often were built along the banks of rivers for half a mile or more. During the summer months, they tended to use more temporary shelters made from the reeds and bulrushes found along the rivers. Tule (Schoenoplectus acutus), which was flexible, strong, and abundant along the freshwater lakes, rivers, and marshes that once formed the Klamath Basin, was used for many finished products, including baskets, moccasins, hats, woven leggings, fishing rafts, and summer huts. It could also be dried and processed into a kind of flour and eaten.

Modoc religious and spiritual traditions have been the subject of considerable study by anthropologists. Much of their findings reflect nineteenth- and twentieth-century religious practices, which were highly influenced by the introduction of Christianity and millenarian movements such as the Ghost Dance. Before contact with EuroAmericans, it appears that Modoc religious belief focused largely on a series of age-appropriate vision quests and the cultivation of guardian spirits. Elaborate sweat houses, used by Modoc of all genders, often had a dual purpose, as a forum for conducting business and socializing and a community center for prayer and other religious activities.

EuroAmerican Settlement

Although accounts of Spanish missionaries or traders in Modoc territory mark the earliest evidence of non-Native contact before the 1820s, the influences of European society were primarily indirect. Trade goods, including horses, began arriving in the region along established Indigenous trade routes through the northern Great Basin, significantly altering economic and political relationships.

As the competition for access to trade goods intensified, captive-taking took on new meanings and significance for the Modoc. Prior to the 1820s and 1830s, Modoc people only occasionally took captives in war or in the course of community feuds. Those few who were taken were often returned or let go after a period of time or were forcibly adopted as kin; social taboos tended to protect them from abuse and extreme violence. During the 1830s and 1840s, however, the Modoc expanded their influence throughout the Pacific Northwest and the Intermountain West, and they became middlemen in the region’s expanding slave trade, which was centered in present-day The Dalles.

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, EuroAmerican settlers entered the Klamath Basin in large numbers, destabilizing the region through a series of bloody wars. To the south, murder and mayhem reigned in the goldfields of California, characterizing a period of violence that transformed the lives of the Modoc people. The U.S. government removed most of the Modoc’s neighbors to the west to distant or marginal reservations, while those in California suffered genocide. Scholars estimate that some 80 percent of California Indians died from violence or the impact of displacement during the upheaval following the Gold Rush.

The flood of settlers into the region also altered its economics. The establishment of cities and towns such as Yreka integrated Modoc into an emerging labor market, often on unequal terms. Indigenous men found employment on ranches and farms as wage laborers, while Indigenous women sometimes worked as sex workers and domestic laborers. By the early 1870s, tensions in relations between Modoc people and resettlers had resulted in the Modoc War.

The War, 1872–1873

The Modoc War was a five-month-long peace-negotiation-turned-campaign-of-extermination that forever changed the world for the Modoc people. It began shortly before dawn on November 29, 1872, when soldiers of the U.S. Army arrived at the Modoc village on the banks of Lost River and attempted to force headman Captain Jack and several of his followers to return to the Klamath Reservation. The Modoc had signed the treaty of 1864, which remains today the basis of their nation-to-nation relationship with the United States. The treaty reserved over one million acres of land and established the Klamath Reservation as a site of settlement for the Modoc and Yahooskin within the traditional territory of the Klamath Indians. In return for abandoning their villages along the Lost River, the government promised to protect the Modoc from further settler violence and guaranteed thousands of dollars in supplies over the next fifteen years.

The government failed to deliver on the promised supplies, and conditions on the Klamath Reservation soon proved intolerable for Captain Jack and his followers. The reservation was within the traditional territory of the Klamath, and tensions over the lack of government supplies increased a rift between Klamath and Modoc people on the reservation. This partly contributed to the Modoc’s decision to leave. “I do not want my men to be slaves for these Indians, and they shall not be,” Captain Jack is reported to have said. “My people are just as good as these Indians.”

In 1870, Captain Jack renounced the treaty and left the reservation with some 300 followers. In response, the U.S. Army sent soldiers to the Lost River villages where Captain Jack and his followers were living. The Modoc resisted the army’s demands that they return to the reservation. The resulting war pitted nearly a thousand U.S. Army soldiers against approximately fifty-three Modoc warriors and their families.

The Modoc War became a national and international sensation when the Modoc attacked the presidential Peace Commission during negotiations on April 11, 1873, killing two of its members, Gen. E. R. S. Canby and Rev. Eleazer Thomas, and wounding the third, Alfred Meacham. Newspapers across the nation and around the world called the Modoc “murderers” and labeled their resistance “base treachery.” After the killing of Canby and Thomas, the press and government officials issued public calls for the “utter extermination” of the Modoc people. The Modoc War ended six weeks later when Captain Jack and a handful of his followers surrendered. He and three other Modoc men were executed on October 3, 1873.

Exile

On October 12, 1873, Captain Jack’s followers—155 Modoc: 42 men, 59 women, and 54 children—were sent by wagon and train to Oklahoma Territory. The 2,000-mile journey took over a month. When they arrived at the Quapaw Reservation, they were tired, hungry, and without shelter, and the government initially offered little support. By 1879, 54 people had died.

Over the next decade, as memory of the Modoc War began to slowly fade, some exiled Modoc returned to the Klamath Reservation. In 1886, eight Modoc, who had been exiled to Oklahoma—including Peter Schonchin, the son of Schonchin John, one of those executed alongside Captain Jack—quietly returned to Oregon. Between 1888 and 1891, the federal government surveyed and platted the 4,000-acre Modoc Reserve on the Quapaw Reservation; and, beginning in 1891, 68 fee-simple patents were transmitted to the Quapaw agent for distribution amongst the 68 remaining members of the Modoc Tribe. This was part of the larger story of the federal government’s efforts to undermine Indigenous sovereignty by dividing up tribal lands and “allotting” them to individual tribal members. The result was a continuing exodus of Modoc people from Oklahoma to Oregon, where the same process was underway on the Klamath Reservation.

By 1893, only 47 Modoc remained on the Quapaw Agency roll. Finally, in 1909, the U.S. government officially allowed the Modoc to return to Oregon (some remained in Oklahoma). Despite the hardships and challenges, the Modoc survived through hard work and perseverance and continue as a people in both Oregon and Oklahoma.

Modoc in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

In 1953, Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108, which called for the immediate termination of all Indigenous tribes in California, New York, Florida, and Texas, as well as the Flathead, Menominee, Potawatomi, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, and Klamath tribes, including the Modoc. On August 13, 1954, Congress passed Public Law 587, the Klamath Termination Act. Under the act, federal supervision of tribal assets, including tribal lands, was ended, and the special status of the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Paiute people ceased to exist. Tribal lands were to be sold and the proceeds disturbed among tribal members, providing they chose to withdraw from the tribe.

Members of the Tribes had a difficult choice: they could either remain members or withdraw and receive a share of the proceeds. In the end, three-quarters of them decided to withdraw and accept payment. The Klamath Tribes were officially terminated in 1961, and what remained of the former Klamath Reservation was either sold to private companies such as Crown Zellerbach Paper Co. or folded into federal forestland reserves. Today, most of the former reservation lands are part of the Fremont–Winema National Forest.

Historians generally agree that termination was an unmitigated disaster for Indigenous communities. It undermined tribal autonomy, harmed Indigenous culture, lowered educational attainment among Indigenous communities, negatively affected tribal economies, and damaged the health of community members. For the Modoc people, termination increased rates of poverty, alcoholism, infant mortality, and suicide and resulted in disintegration of families, poorer housing, and disproportionately high rates of incarceration.

Despite these outcomes, Indigenous people continued to fight for their rights. Termination resulted in a series of lawsuits that would ultimately lead to the restoration of many tribes, and Modoc and Klamath individuals continued to practice their rights as reserved by treaty. In 1974, the federal courts ruled in Kimball v. Callahan that five former members of the Klamath Tribe, despite having withdrawn from the tribe under Public Law 587, had retained hunting and fishing rights as guaranteed in the Treaty of 1864. It also held that the Klamath Tribes had to be consulted in land management decisions when those decisions affected their treaty rights. In other words, termination had not ended treaty rights or the federal government’s relationship with the Klamath Tribes.

In 1978, Congress restored federal recognition of the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma. Nearly a decade later, in 1986, Congress re-recognized the Klamath Tribes as a sovereign entity through the Klamath Indian Tribe Restoration Act. Although the act did not restore former reservation lands to the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Paiute, it laid the groundwork for tribally led economic redevelopment in the region, resulting in tribal enterprises such as the Kla-Mo-Ya Casino.

In the early-twenty-first century, a series of conflicts over water rights between the Klamath Tribes and Klamath Basin farmers drew national attention, resulting in discussions between the states of California and Oregon; the federal government; the Klamath, Karuk, and Yurok tribes; and many other private and public parties. The resulting Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement, signed in February 2010, sought to restore portions of the Klamath River’s natural habitat, provide assurances for river usage and water rights within the Klamath Basin, and begin the process of removing a series of dams to help restore salmon populations. Congress failed to pass necessary legislation before the January 1, 2016, deadline. And while new agreements have been put in place, the future health and prosperity of the Klamath River Basin remains uncertain and continues to be an issue of great concern for many Modoc people.

-

![]()

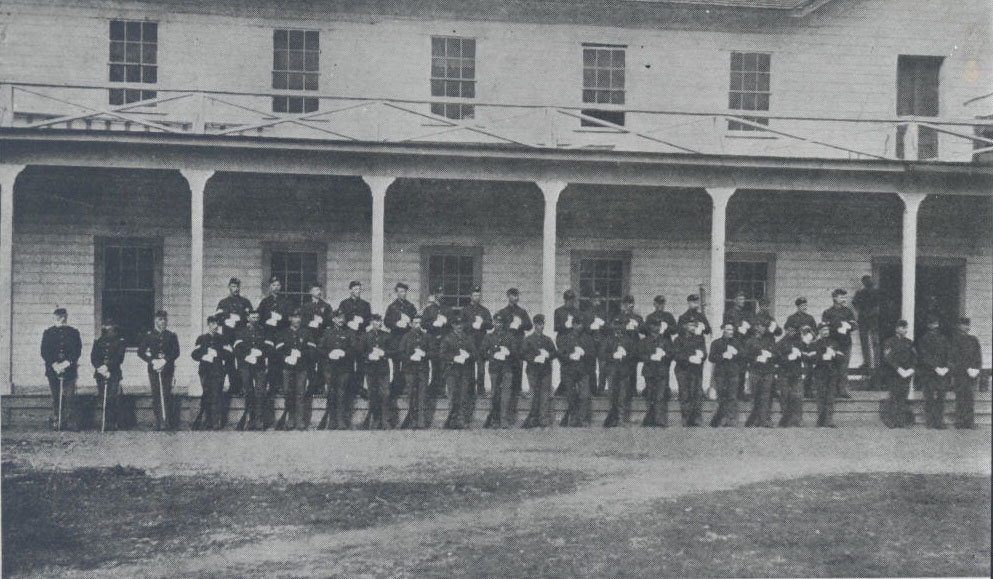

Modoc survivors of the war after their relocation to the Quapaw Indian Agency, Kansas. (cropped).

Courtesy Library of Congress, photograph by McCarty, Baxter Springs, Kansas. -

![]()

Winema (Modoc) and her son, Jeff Riddle (Modoc), c. 1873.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Louis Heller, LC-USZ62-114599 -

![]()

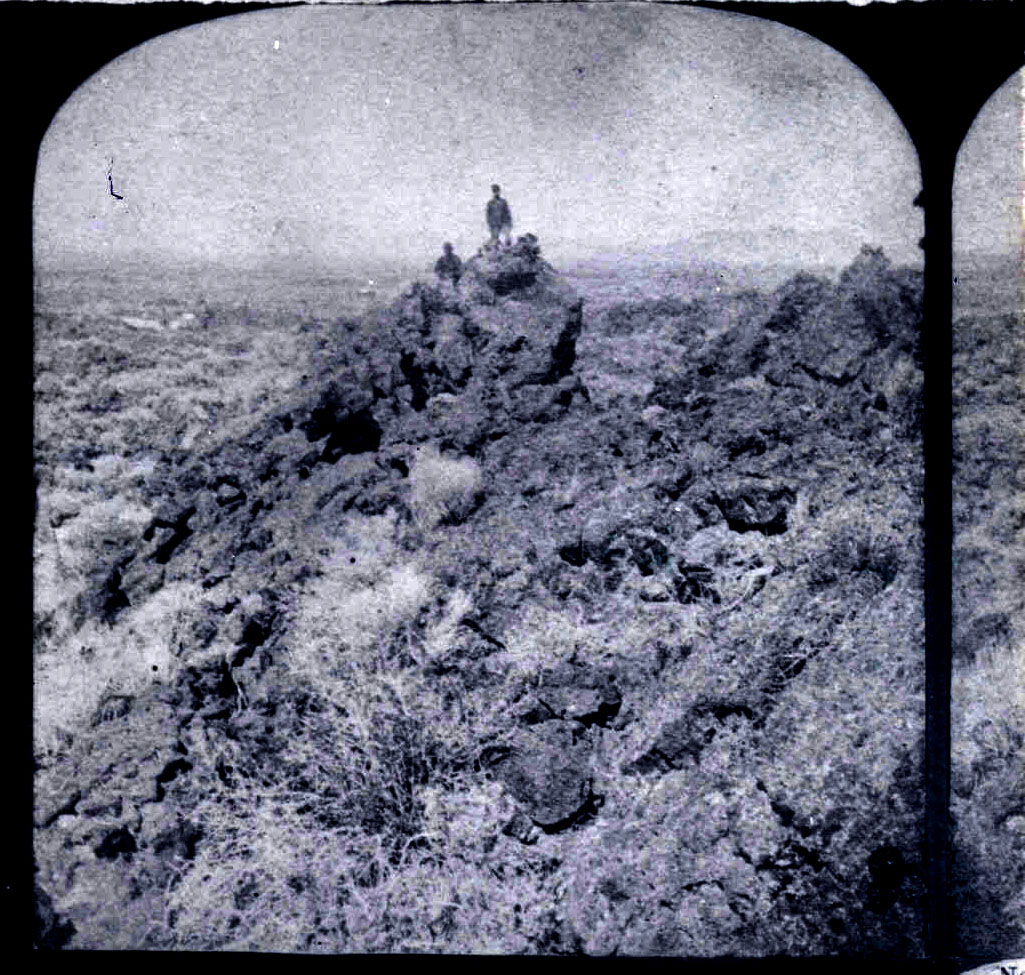

Tule Lake, California, within the Modoc homelands.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, William L. Finley Photographs Collection, circa 1900-1940; Org. Lot 369; b20; FinleyA2282 -

![Scarface Charley, James Long, Bogus Charley, Shacknasty Jim, Hooker Jim]()

Modoc prisoners, c. 1873.

Scarface Charley, James Long, Bogus Charley, Shacknasty Jim, Hooker Jim Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 016549

-

![]()

O.C. Applegate and Frank Riddle with Modoc women, 1873.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi26543

-

![]()

Kintpuash (Captain Jack) (Modoc), 1864.

Courtesy L.A. Southwest Museum

-

![]()

Lower Klamath Lake.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Finley, OrgLot369_FinleyD1578 -

![]()

Klamath Indian Agency.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Neg. #51002, File Folder #562

-

![]()

Klamath Indian Agency, 1886.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHi 51085, Photo File #562

-

![]()

School girls at Klamath Indian Agency.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 53239, Photo File #562

-

![]()

Modoc Tribe float in Klamath Railroad Day parade.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba011354, photo file 618c

Related Entries

-

![Crisis in the Klamath Basin (documentary film)]()

Crisis in the Klamath Basin (documentary film)

The 1958 KGW-TV documentary Crisis in the Klamath Basin broke important…

-

![Fort Klamath]()

Fort Klamath

During the Civil War era, tens of thousands of people immigrated to the…

-

![Judson Dean "Judd" Howard (1878?-1961)]()

Judson Dean "Judd" Howard (1878?-1961)

Judson Dean “Judd” Howard is remembered as “The Man Behind the Monument…

-

![Kintpuash (Captain Jack) (c. 1837-1873)]()

Kintpuash (Captain Jack) (c. 1837-1873)

Kintpuash (Strikes the Water Brashly), also known as Captain Jack an…

-

![Lower Klamath Lake]()

Lower Klamath Lake

Before human engineering altered the upper Klamath Basin, water flowed …

-

![Modoc War]()

Modoc War

The Modoc War, waged mostly over the winter and spring of 1872-1873, th…

-

![Termination and Restoration in Oregon]()

Termination and Restoration in Oregon

Termination Of the federal-Indian policies introduced to American Indi…

-

![Tules]()

Tules

In Oregon and much of the western United States, tule is the common nam…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cothran, Boyd. “Loks and the Yámatni: Slaves, Chiefs, Medicine Men, and the Indigenous Political Landscape of the Upper Klamath Basin, 1820s-1860s.” In Linking the Histories of Slavery in North America, edited by James F. Brooks and Bonnie Martin, 97-123. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press, 2015.

Cothran, Boyd. Remembering the Modoc War: Redemptive Violence and the Making of American Innocence. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

James, Cheewa. Modoc: The Tribe That Wouldn't Die. Happy Camp, CA: Naturegraph, 2008.

Most, Stephen. River of Renewal: Myth and History in the Klamath Basin. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2006.

Ray, Verne F. Primitive Pragmatists: The Modoc Indians of Northern California. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1963.

Stern, Theodore. The Klamath Tribe: A People and Their Reservation. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965.

Stern, Theodore. “Klamath and Modoc.” In Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 12., 446-66. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Wilkinson, Charles. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. New York, NY: Norton, 2005.