Muller v. Oregon, one of the most important U.S. Supreme Court cases of the Progressive Era, upheld an Oregon law limiting the workday for female wage earners to ten hours. The case established a precedent in 1908 to expand the reach of state activity into the realm of protective labor legislation. The defense, in what is known as the Brandeis Brief, circumvented previous Supreme Court decisions that had stressed workers' freedom to contract free of state regulation. The brief de-emphasized formal legal logic by using social science and medical information to argue that overwork was especially detrimental to female health and that the state had an interest in counteracting it. The court concurred on the grounds that society had an interest in protecting the bodies of potential mothers, whom the majority opinion referred to as “bearers of the race,” opening the door for an expanded state power to regulate the workplace on the basis of sex differences.

The case originated when Hans Curt Muller, the owner of the Grand Laundry, compelled Emma Gotcher, unionist and the wife of a leader of the Shirtwaist and Laundryworkers’ Union, to work longer than the ten hours allowed by the state law. A local judge fined Muller, who appealed the decision, putting the case on the path that would lead to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Muller’s attorney for the appeal was William Fenton, an opponent of state intervention in the economy. In making his case, Fenton stressed that women, as citizens, deserved the same rights and privileges as other citizens—and that meant the freedom to make their own bargains and to contract freely. While the argument aimed to prevent the state from gaining any right to regulate economic activity, it also expressed the sentiment of many feminists of the era, including Clara Colby, the editor of the Portland-based Woman’s Tribune: “The state has no right to lay any disability upon woman as an individual.” Colby was no opponent of state regulation; she supported women’s pensions and expressed a willingness to support laws that protect all workers.

Yet, many advocates of reform, like Florence Kelley of the National Consumers' Union, believed that the protection of women would open the door for greater state protections of workers. She sought a means to get around Supreme Court decisions that had closed down the ungendered path. Most notably, in the Lochner decision of 1905, the Court had ruled unconstitutional a New York law that had limited the hours of employment bakeries could impose on their workers, all of whom were male, on the grounds that it was an unhealthful profession. Kelley sought out attorney Louis Brandeis to write the defense brief in the Muller case. His use of social scientific research to argue that women were adversely affected by long hours of labor was an attempt to get around the Lochner decision.

In arguing that physically weaker women deserved protection, Brandeis made more than a physiological argument; it also was grounded in beliefs about family and gender. Brandeis argued that future mothers would be harmed by overwork in factories, reducing their capacity for childbearing and resulting in weakened children. Further, families would be harmed by the loss of female service in the home.

The state’s case reflected the position taken by the American Federation of Labor, whose leader Samuel Gompers had long stressed a “voluntarist” approach to hours and wages for men and the desire for men to be paid a “living wage” that would allow families to do without wages earned by women.

By focusing on the distinctive roles of women as mothers, Brandeis sought to get around the Supreme Court's penchant for limiting governmental regulation of the freedom to contract. Many historians have been critical of this decision, noting much as Clara Colby did at the time, that it ingrained into law female dependency in the workplace.

-

![Louis Brandeis]()

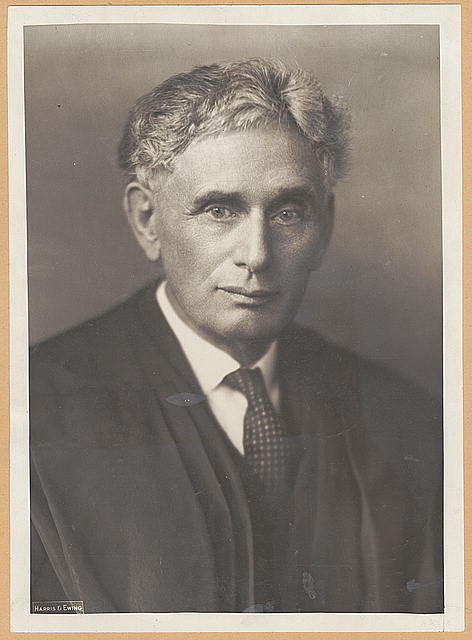

Louis Brandeis.

Louis Brandeis Courtesy Library of Congress, ppmsca06024r

-

![Clara Colby]()

Clara Colby.

Clara Colby Courtesy Library of Congress, 3b20609_150px

-

![Florence Kelley]()

Florence Kelley.

Florence Kelley Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-USZ62_73260

Related Entries

-

![Caroline Gleason (1886-1962)]()

Caroline Gleason (1886-1962)

Caroline J. Gleason—Roman Catholic nun, social reformer, and educator—h…

-

![Oregon Industrial Welfare Commission]()

Oregon Industrial Welfare Commission

In the spring of 1913, the Oregon legislature created the first compuls…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Erickson, Nancy S. "Muller v. Oregon Reconsidered: The Origins of a Sex-Based Doctrine of Liberty of Contract." Labor History 30 (1989), 228-50.

Hart, Vivien. Bound by our Constitution: Women, Workers, and the Minimum Wage. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Johnson, Elaine Gale Zahnd. "Protective Legislation and Women's Work: Oregon's Ten-Hour Law and the Muller v. Oregon Case, 1900-1913." Ph.D Dissertation, University of Oregon, 1982.

Johnston, Robert. The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2006.