Sauvie Island, at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, was the geographical focus of a sizable body of Native art pieces in the Chinookan Art Style, a unique art form characteristic of the Native peoples of the lower Columbia River. Many of the pieces are preserved in the collections of the Portland Art Museum and the Oregon Historical Society, and others are held by museums elsewhere. A sizable number, taken by collectors from abandoned sites in the first century after settlement, remain in private collections out of the public eye.

During the early nineteenth century, Sauvie Island and the lowlands around it were occupied by twenty villages. All of the traditional pieces were created before the great "fever and ague" epidemics of the early 1830s, when over 90 percent of the Wapato (Wappato) people died and their villages were abandoned. The epidemic undoubtedly killed most Native artists, taking with them their specialized knowledge of the conventions of the style, its socioreligious significance, and how to produce it; so it is difficult today to reconstruct how and why the art was created.

The artworks from Sauvie Island itself are portable, created in stone (basalt and lava) and elk antler. There are pieces in other media from the larger Portland Basin, including wood figural posts from the Cascades Rapids, which were probably representative of a larger number of wood pieces that have not survived; small fired clay objects from the Lake River area; and a few petroglyphs from Willamette Falls.

The Chinookan Art Style was practiced by all Lower Columbia Chinookan speakers from present-day Astoria to The Dalles, as well as by many of their neighbors. It was very different from the better-known North Coast Art Style, as defined by Bill Holm. Most works are anthropomorphic or zoomorphic. The anthropomorphic pieces share conventions such as simple two- or three-plane faces, single nose-brow lines, and conventionalized ribs and spinal columns. The zoomorphic pieces show owls (usually a barn-owl type face), beavers (recognizable by the tail), seals, frogs, and other creatures; but few of the zoomorphic depictions are clear and were probably intentionally made to be ambiguous.

The pieces are all assumed by researchers to have socioreligious significance, but their precise meanings are unclear due to the early loss of the art form. Many may represent the owner's guardian spirit or spirit helper, and there are a few historical citations in the greater Portland Basin that associate pieces with burial canoes or vault cemeteries. Northwest mobile stone art also comes from The Dalles and the Lower Fraser Valley in southwestern British Columbia. Artworks from all three areas sometimes have basins on the top, which in the Fraser Valley are said to have held water used in rituals. Pieces from the Portland Basin and the Fraser have been called "weather stones," and some of the small Lake River clays have holes that suggest they were worn as amulets.

Four of the better-known and more spectacular pieces of early Sauvie or Portland-area Native art are in the collections of the Portland Art Museum, the Burke Museum at the University of Washington, and the Oregon Historical Society.

- The Portland Art Museum's four-and-a-half-foot tall anthropomorphic basalt upright has a classic two-plane face, prominent ribs, hints of a headdress, and a phallus. The lower quarter is unworked, similar to two other large Sauvie basalt uprights in the Oregon Historical Society collection. The piece is a recent purchase from a private party, and it (or one like it) may be the large upright weather stone from the interior of Sauvie Island, noted by Hudson’s Bay Company Governor George Simpson in 1841.

- The University of Washington Burke Museum's elk-antler female figure is a small, seven-and-a-half-inch mobile piece with a typical Chinookan-style face, as well as a short dress and geometric figures on the legs that may represent tattoos. On her back is a baby in a carrying-cradle.

- The Oregon Historical Society piece, originally interpreted by scholar Paul Wingert as an owl, appears to be a split figure of some other animal, viewed from above. It has the typical Chinookan stylized backbone and ribs, but what were thought to be an owl's ears may instead be front paws. The piece may be intentionally ambiguous.

- A twenty-three-inch-tall lava piece has a face on the upper two-thirds, showing the joined nose-brow ridge, ovoid eyes, and a mouth with tongue that are associated with the well-known Tsagiglalal petroglyph at Horsethief Lake Park north of The Dalles. It is now in a private collection.

Though a continuing thread in Chinookan Style and Sauvie Island Native art was broken by the events and upsets in the mid-nineteenth century, several artists, Native and non-Native, are relearning its conventions and producing remarkable pieces that are both original in composition and faithful to the style. Public art at the Cathlapotle plankhouse, Blue Lake Park, and Tilikum Crossing Bridge are examples of the revitalized style, and the Portland Art Museum's 2015-2016 "Thlatwa Thlatwa: Indigenous Currents" exhibit celebrated three contemporary practitioners.

-

![]()

Owl sculpture, Sauvie Island.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Museum, OrHi37732

-

![]()

Rock carvings found on Sauvie Island.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi9562

-

![]()

Sauvie Island and Multnomah Channel, aerial.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 672

Related Entries

-

![Chinookan Plankhouses]()

Chinookan Plankhouses

The Chinookan peoples of the Lower Columbia River built a variety of sh…

-

![Multnomah (Sauvie Island Indian Village)]()

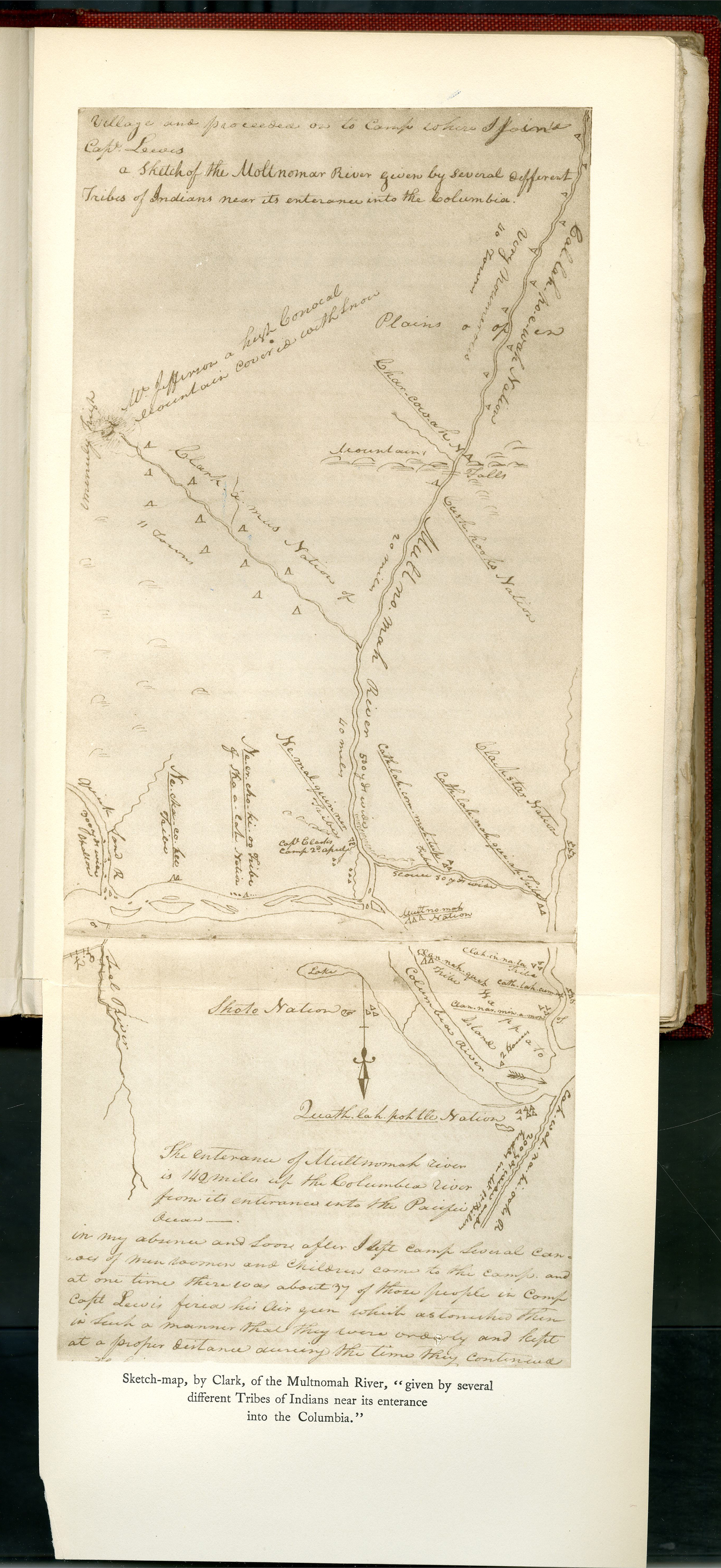

Multnomah (Sauvie Island Indian Village)

"Multnomah" is a word familiar to Oregonians as the name of a county an…

-

![Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s]()

Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s

During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American …

-

![Rock Art]()

Rock Art

Rock art is one of the most common types of archaeological site in Oreg…

-

![Wapato (Wappato) Valley Indians]()

Wapato (Wappato) Valley Indians

Lewis and Clark called them the "Wappato Indians," the people who inhab…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Duff, Wilson. Images, stone, B.C.: thirty centuries of Northwest coast Indian sculpture. Saanichton B.C.: Hancock House, 1985

Gibbs, George. "George Gibbs' account of Indian mythology in Oregon and Washington territories." Ella Clark, ed. Oregon Historical Quarterly 56.4 (1955-56): 293-325; 57.2: 125-67.

Holm, Bill. Northwest Coast Indian Art: an analysis of form. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965.

Johnson, Tony, and Adam McIsaac. "Lower Columbia River Art." In Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, edited by Robert Boyd, Kenneth Ames, and Tony Johnson, 199-225. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015.

Mercer, Bill. People of the River: Native Arts of the Oregon Territory. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Peterson, Marilyn Sargent. Prehistoric Mobile Stone Sculpture of the lower Columbia River Valley. MA thesis, anthropology. Portland State University, 1978.

Simpson, George. An overland journey round the world during the years 1841 and 1842. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847.

Slocum, Robert and Kenneth Matsen. Shoto Clay: a description of clay artifacts from the Herzog site (45-CL-4) in the lower Columbia region. Portland: Binfords & Mort for the Oregon Archaeological Society, 1968.

Wingert, Paul. Prehistoric Stone Sculpture of the Pacific Northwest. Portland Art Museum, 1952.