When he was elected to the United States Senate in 1954, Richard Neuberger had been at the center of journalistic excellence in the Pacific Northwest for two decades. At the age of twenty, he had gained national renown for “The New Germany,” published in The Nation in October 1933, one of the earliest criticisms of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis’ rise to power. By the time he was twenty-seven years old, Neuberger was the author or coauthor of three books, including Our Promised Land (1938), which is considered a Northwest classic.

Richard Neuberger was born in Portland on December 26, 1912, to Isaac and Ruth Neuberger. His mother, who operated the family’s popular restaurant, the Bohemian, on Southwest Washington Street, raised her son in the Jewish faith and influenced his early conservatism. Neuberger first displayed his gift for writing at Lincoln High School as a sportswriter for the school newspaper, a talent that attracted the attention of Oregonian columnist William L.H. Gregory. With Gregory’s support, the Oregonian hired Neuberger, first as a copy clerk and then as a reporter.

Off to the University of Oregon in the fall of 1931, Neuberger joined the school newspaper, the Oregon Daily Emerald, as sports editor. Within a year, he was appointed editor of the paper, a position he used in 1932 to endorse President Herbert Hoover’s reelection bid against Democratic candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt. Before long, however, Stephen Kahn, Neuberger’s college roommate, opened the young editor’s eyes to the social and economic chaos associated with the Great Depression. By the time Roosevelt was inaugurated in March 1933, Neuberger had become an ardent New Deal reformer.

In the summer of 1933, Neuberger toured Europe, including Germany, with his Uncle Julius. Following the tradition of investigative journalism, he walked the back alleys of German cities, interviewing people and gathering the information he published in The Nation about Hitler’s sordid rise to power. Within three years, he wrote additional articles for leading journals and newspapers. The world beyond the academy was proving more alluring than university life.

Still without a journalism degree, Neuberger made an abortive effort to study law under the guidance of University of Oregon law school dean Wayne Morse, who admired Neuberger’s writing talents. When Morse urged his prospective student to make up uncompleted courses before beginning law school, Neuberger responded: “I only want to know the law. Aside from that, to heck with degrees.” He skipped classes and cribbed notes, and eventually a faculty committee accused him of plagiarism. With Morse’s vigorous defense, the charges were dropped. Morse, however, urged Neuberger to leave law school, advice that persuaded the youthful Neuberger to pursue journalism full time.

Neuberger served as Northwest correspondent for the New York Times from 1936 to 1954. During the late 1930s, he was also part of Oregon’s insurgent politics, joining forces with the Oregon Commonwealth Federation to reform the state’s reactionary Democratic Party. He was always on the move, looking for writing material and following senators such as William E. Borah (Republican from Idaho) or Burton Wheeler (Democrat from Montana). By the close of the decade, he was the region’s preeminent journalist and had a growing national reputation.

Although his travels took him far afield, Neuberger met the tall, self-assured Maurine Brown—the woman who would become his wife—in the early 1940s in Portland. He served a brief stint in the Oregon House before World War II and then enlisted in the army, serving as an officer in the effort to construct the Alaskan Military Highway. Neuberger was transferred to Washington, D.C., in early 1945 and later that year was assigned to the American delegation at the United Nations conference in San Francisco, where he met Adlai Stevenson, an advisor to the U.S. representatives. In late 1945, after his discharge, Neuberger married Maurine Brown, the beginning of a mutual engagement with journalism and politics that would push the couple to the forefront of American politics. His writing after the war would give him great influence among Portland’s literary community.

After refusing opportunities to run for statewide office, he was elected to the Oregon Senate in 1948. With a growing national reputation, the energetic Neuberger jumped into the U.S. Senate race against conservative Republican incumbent Guy Cordon in 1954. With the substantial support of Senator Wayne Morse—an Independent soon to register as a Democrat—Neuberger won a narrow victory and became the first Oregon Democrat elected to the U.S. Senate since 1914. As the state’s junior senator, he pursued liberal policies: public power, civil rights, clean-water initiatives, good forestry practices, and development of the Columbia River. He was also one of the key people instrumental in transforming fledgling Portland State College into a modern university, and Neuburger Hall on campus is a tribute to this contribution.

Northwesterners, Neuberger firmly believed, could enjoy both inexpensive hydropower and plentiful salmon runs. Before his election to the Senate, he joined Senator Morse in supporting legislation to build a 720-foot-high dam in spectacular Hells Canyon on the Oregon-Idaho state line. In that sense, Neuberger was at one with politicians such as Idaho Senator Frank Church who prided themselves as conservationists but who also supported big water projects. One of Neuberger’s avowed enemies was the Idaho Power Company, which subsequently built three hydroelectric dams in the upper canyon.

Neuberger’s Senate years coincided with the termination of the Klamath Indian Tribe, which ended the trust relationship the tribe had with the federal government. Although Neuberger’s part in the culturally and economically disastrous policy was limited to the period when the Klamath Termination Act (Public Law 587) was working its way through Congress, he was instrumental in assuring federal purchase of the reservation’s lush timber stands and turning it into the Winema National Forest. As critics have argued, the conservationist Neuberger was more interested in what happened to the timber than to the people who lived on the reservation. During his years as a U.S. senator, Neuberger also laid the groundwork for the creation of the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area.

In the late 1950s, even as he fought his long bout with cancer, he used his literary talents to garner support for cancer research, publishing “When I Learned I had Cancer” in Harper’s in June 1959. Richard Neuberger died on March 9, 1960. Maurine Neuberger successfully ran for his Senate seat in the fall election.

-

![Richard Neuberger (l) with Adlai Stevenson, 1954.]()

Neuberger, Richard, with Stevenson, Adlai, 1954 CN 013528.

Richard Neuberger (l) with Adlai Stevenson, 1954. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., CN 013528

Related Entries

-

![Maurine Neuberger (1906-2000)]()

Maurine Neuberger (1906-2000)

Maurine Brown Neuberger entered politics as an Oregon state legislator …

-

![Oregon Commonwealth Federation]()

Oregon Commonwealth Federation

Following the inaugural meeting of the Oregon Commonwealth Federation (…

-

![Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area]()

Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area

Created by Congress in 1972, the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area …

-

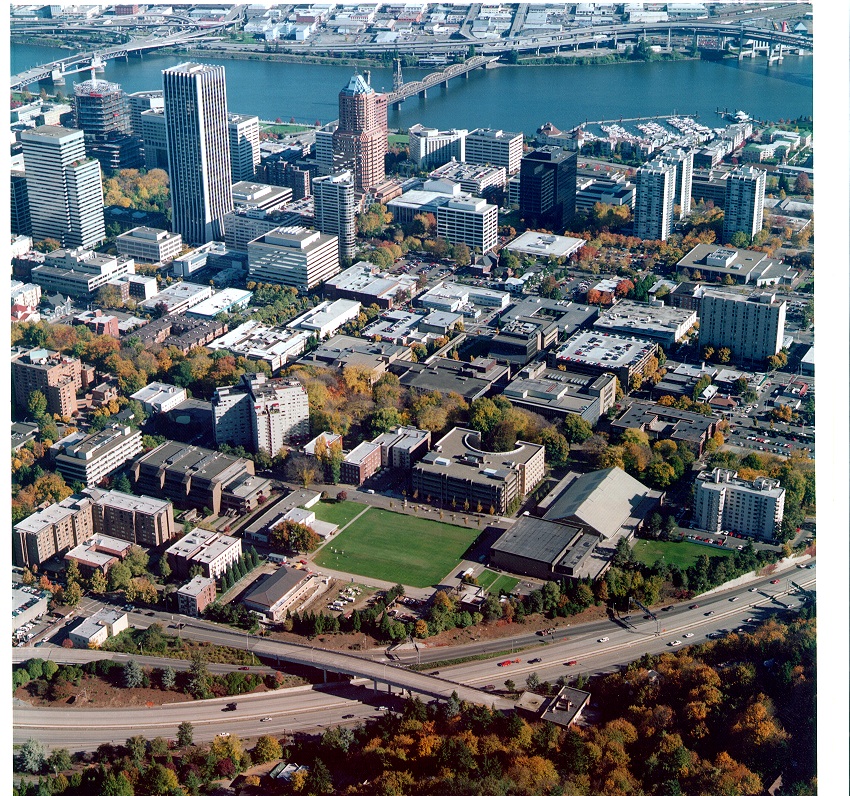

![Portland State University]()

Portland State University

Located in downtown Portland, Portland State University is Oregon’s urb…

-

![The Oregonian]()

The Oregonian

The Oregonian, the oldest newspaper in continuous production west of Sa…

-

![Wayne Morse (1900-1974)]()

Wayne Morse (1900-1974)

Wayne Morse and the Vietnam War: the name and the conflict will be fore…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Neuberger, Richard L. Our Promised Land. New York: Macmillan Co., 1938.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Conflict: The Oregon Story, 1940-2000. Seattle, Wash.: Universtiy of Washington Press, 1997.