In the course of the Spanish-American War, the United States attacked and occupied the Spanish colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. The Second Oregon Volunteer Infantry was initially sent to the Philippines to defeat the Spanish and aid the islands’ independence movement. But the U.S. soon changed tack, abandoning its alliance with the Filipinos and annexing the islands from Spain. The Oregon Volunteers participated in the occupation of Spanish Manila and in the brutal land war against Filipino nationalists that followed.

The experience of the Second Oregon Volunteers marked a transition in American foreign policy and in American military organization. The unit traced its genealogy to the First Oregon Volunteers, a militia created in the wake of the Civil War as a frontier force used primarily against Northwest Indian tribes. For the nation, the Spanish-American War represented a shift from U.S. conquests in the American West to conquests abroad. It also marked a transition from the use of irregular volunteer forces to the more professional and bureaucratic armed forces of the twentieth century.

When President William McKinley issued a call for military volunteers in April 1898, Oregonians responded. Over a thousand men trained at a temporary encampment on the site of Portland’s Irving Park. They traveled by rail to the San Francisco Presidio, and then boarded a ship bound for Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines. On May 1, Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet at Manila and then awaited the arrival of U.S. ground troops.

The Oregon Volunteers reached the Philippines in June and soon found themselves in the middle of a complex diplomatic impasse. Filipino nationalists had besieged Spanish Manila by land while Dewey had blockaded the port by sea. Spanish officers, fearing the Filipinos more than the Americans, surrendered the city to the U.S. after a token show of resistance. It was under these circumstances that the Oregon Volunteers entered the city in August, while their nominal Philippine allies remained outside the walls.

U.S. forces occupied Manila for five months while Spanish and U.S. diplomats negotiated a final peace. In the end, the December 10 treaty ceded control of the islands to the United States. With U.S. and Filipino troops still entrenched face-to-face on the outskirts of Manila, little was needed to touch off a second war. In February, a late-night skirmish between guards escalated into a general battle and unleashed a U.S.-Philippine war that would last until 1902. From February to May 1899, Oregon soldiers fought in campaigns east of Manila along the Pasig River and north of Manila in Malolos and Papanga. They fought to control towns and infrastructure and to destroy Philippine forces and their civilian supporters.

Their own accounts of combat reveal the moral, political, and practical complexities of the war. The troops suffered from limited training, outdated equipment, disease, and poor provisioning. On campaign, they fought some conventional battles, but they also burned villages, relocated populations by force, and tortured captives in an attempt to suppress a Philippine insurgency that enjoyed widespread popular support.

Unfamiliar with the languages and cultures of the Philippines, the Oregon Volunteers struggled to make sense of the conflict in relation to their previous experiences. Though the Oregon troops’ period of active campaigning was relatively short, it took place during a time of rapidly escalating brutality. Surviving letters and diaries suggest that the soldiers made sense of the conflict by categorizing their opponents as “Black” or “Indian,” and by describing the Philippine conquests as a continuation of North America’s frontier wars. In the United States, policy makers and journalists debated America’s role in the world and the future of post-colonial states; but on the ground in the Philippines, Oregon soldiers fought a terrifying war that they viewed through the prism of North American racial ideologies.

The Second Oregon Volunteers returned to Manila in May 1899 before shipping home to the U.S. by way of Japan. On August 10, enthusiastic crowds in Portland greeted them, and they were honored in a public ceremony at Multnomah Field.

-

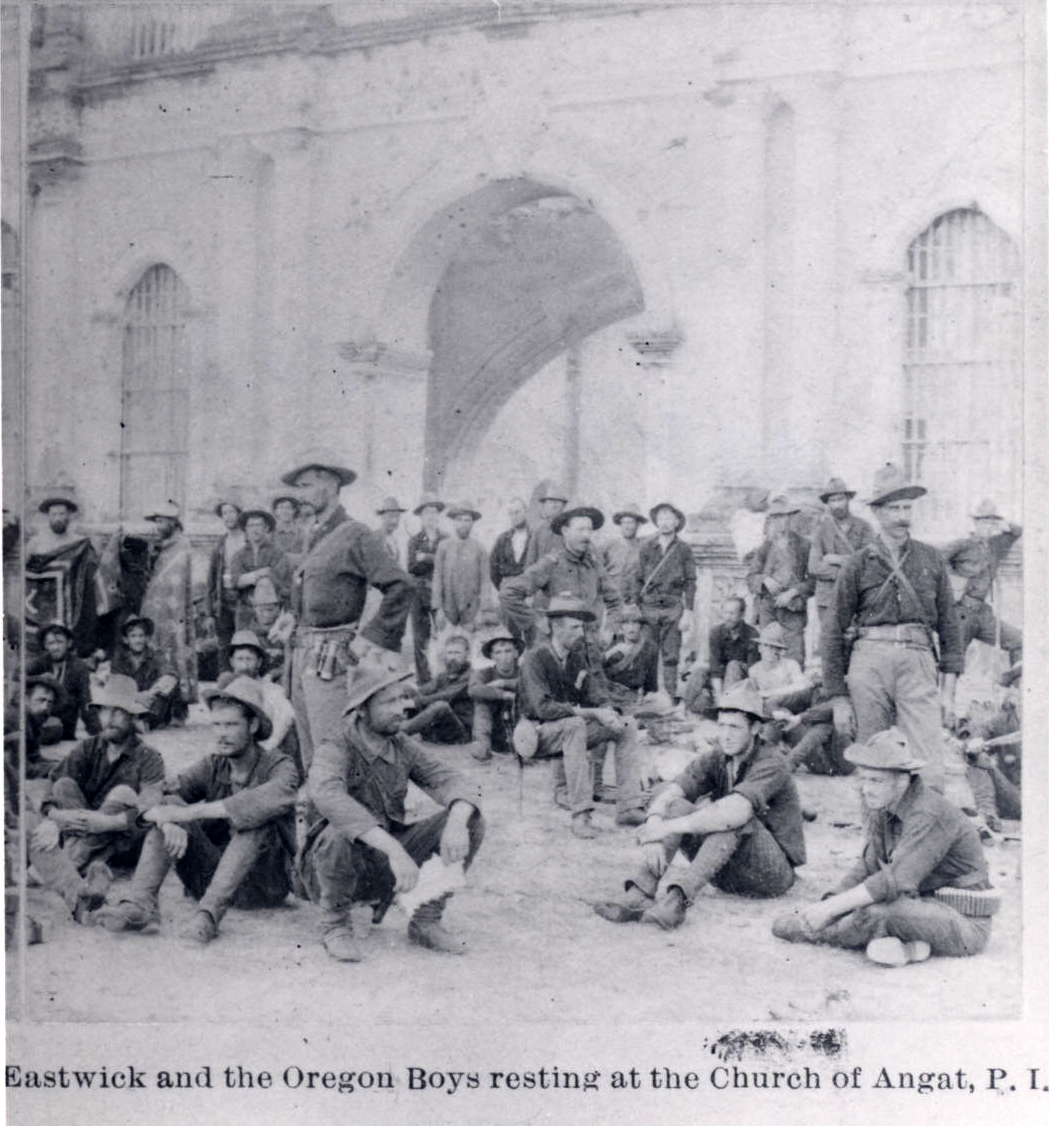

![Major Eastwick and his company rest at a church in Angat.]()

Oregon Volunteers in Angat, Philippines.

Major Eastwick and his company rest at a church in Angat. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Waite served on the battleship Oregon during the Spanish-American War.]()

Edward Waite.

Waite served on the battleship Oregon during the Spanish-American War. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 002523

-

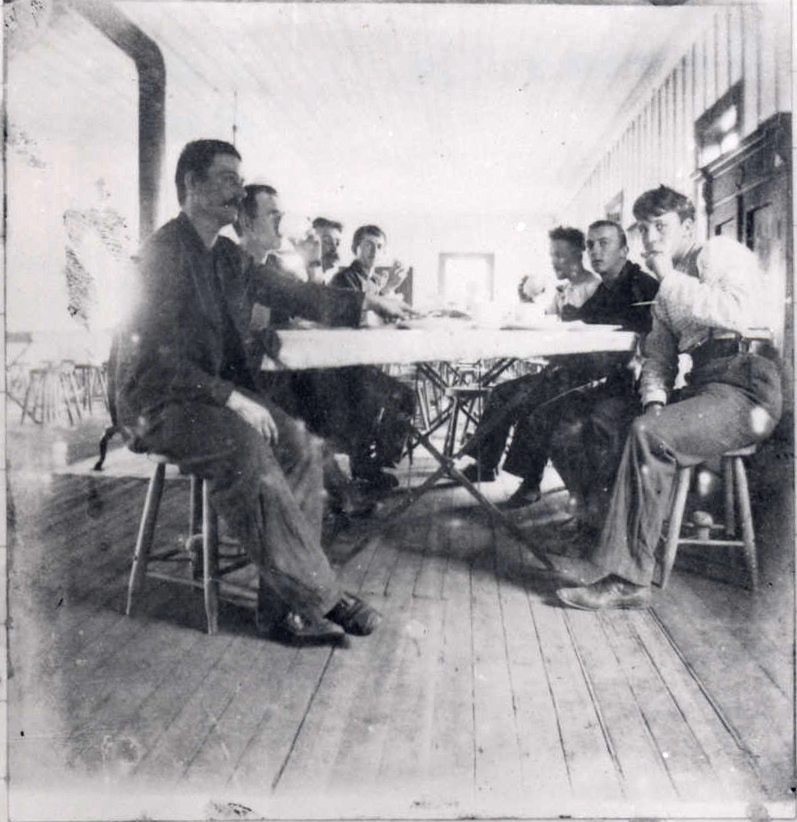

![]()

Manila, Philippines, c. 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 63251

-

![]()

Oregon Volunteers in San Francisco, c. 1899.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017141

-

![]()

Oregon volunteers in San Francisco, c. 1899.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017142

-

![]()

Oregon Volunteers, Battery A, Vancouver Barracks, c. 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019963

-

![]()

Captain and officers of the U.S.S. Oregon, 1897.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017960

-

![]()

2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry in San Francisco, 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 008230

-

![]()

Oregon Volunteers, c. 1899.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017143

-

![Soldiers perform for the camera]()

Oregon Volunteers, Battery A, Vancouver Barracks, c. 1898.

Soldiers perform for the camera Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019964

-

![]()

American train masters in Santiago, Cuba.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 008419

-

![]()

Working force in office in Manila, c. 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017948

-

![A suspension bridge crossing the Pasig River. Photo was taken during the Spanish-American War.]()

Pasig River, Manila Bay.

A suspension bridge crossing the Pasig River. Photo was taken during the Spanish-American War. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 63262

-

![J.D. Tobin inspects government transportation at the U.S.Q.M. (Quartermaster) Corral]()

Camp in Santiago, Cuba, c. 1899.

J.D. Tobin inspects government transportation at the U.S.Q.M. (Quartermaster) Corral Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 008421

-

![Soldiers watch revolutionary forces leave Malabon]()

Oregon volunteers in Malabon, March 26, 1899.

Soldiers watch revolutionary forces leave Malabon Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017138

-

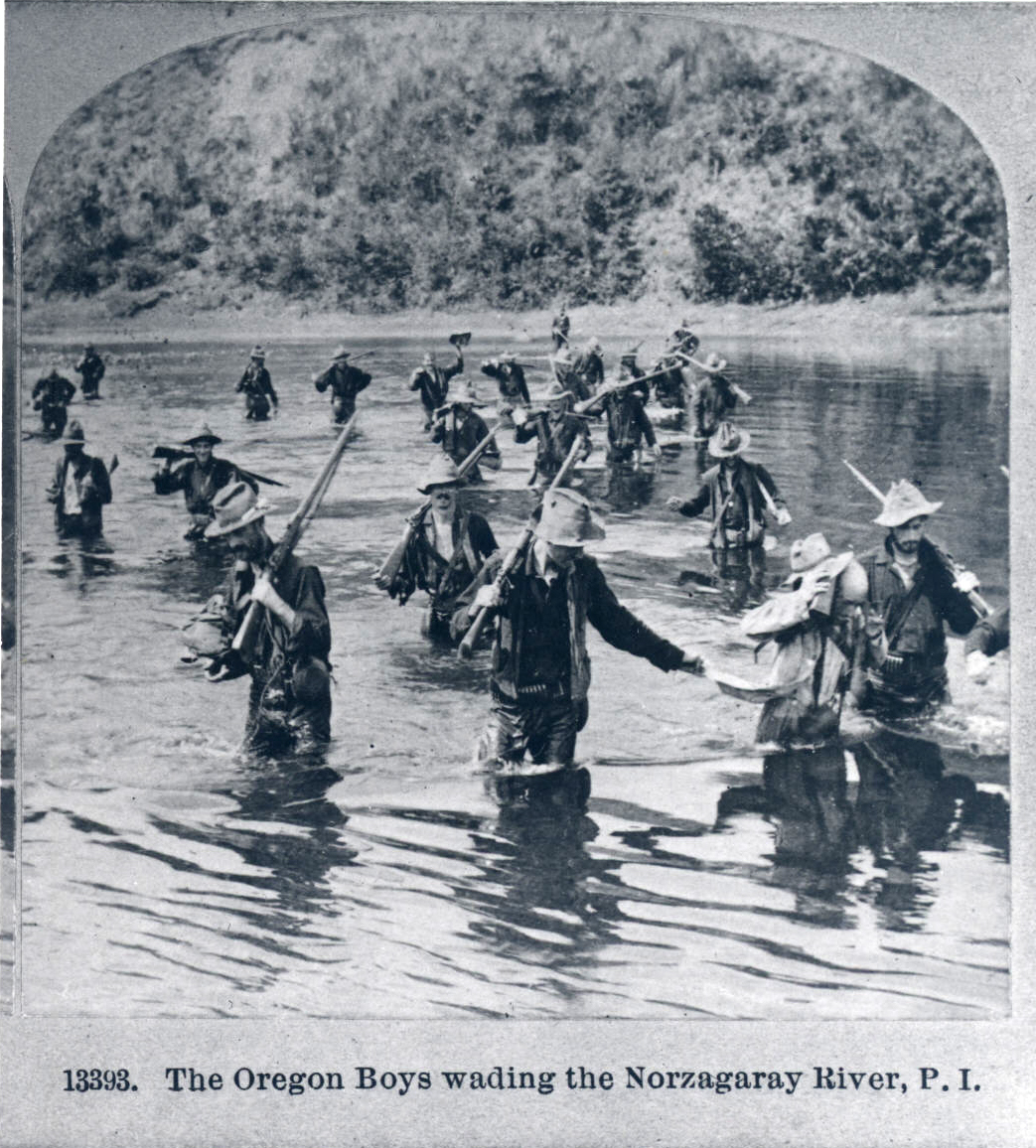

![Wading across the Zagaray River]()

2nd Oregon Volunteers in the Philippines, 1899.

Wading across the Zagaray River Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017137

-

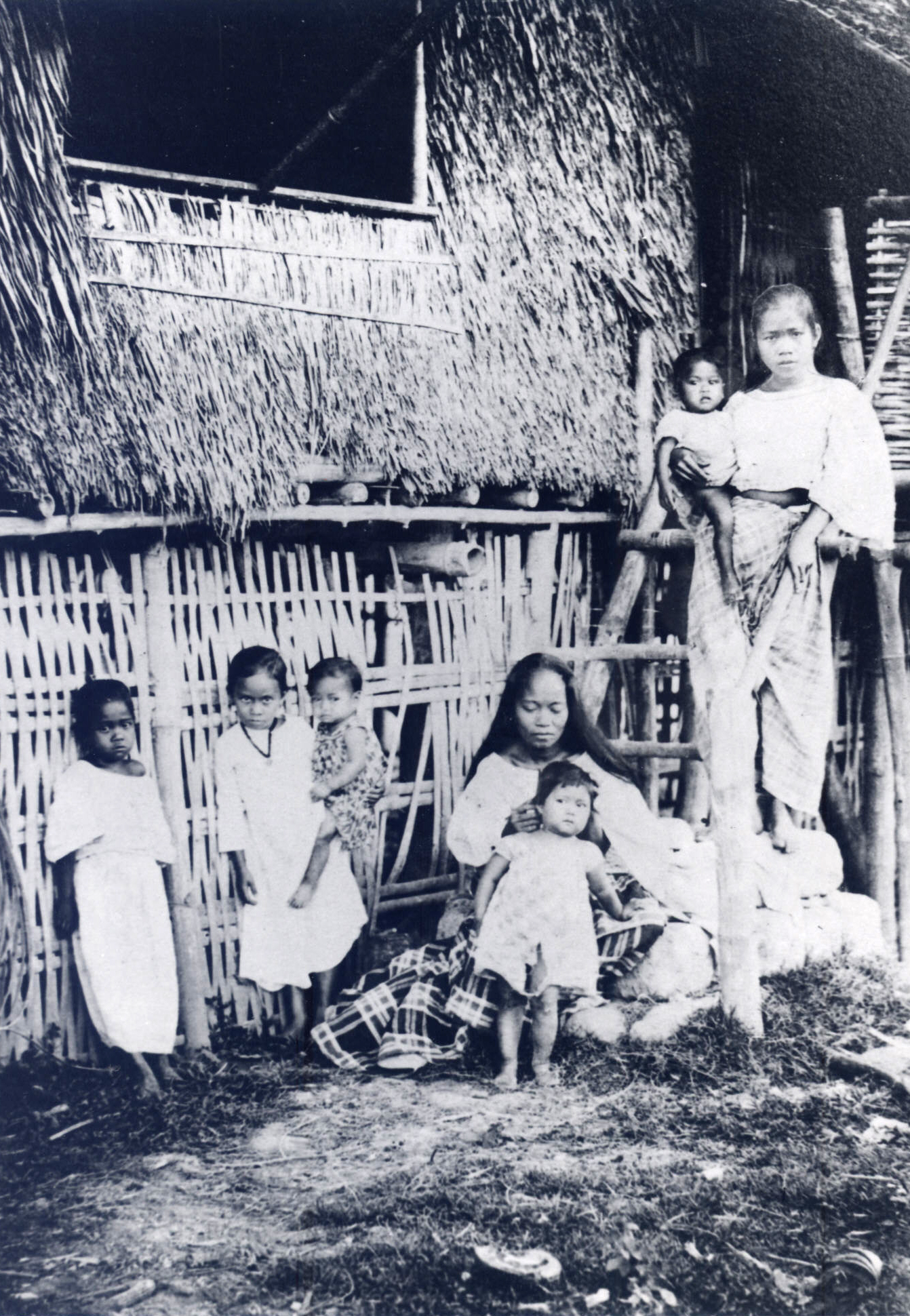

![]()

Family in the Philippines. c. 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 63261

-

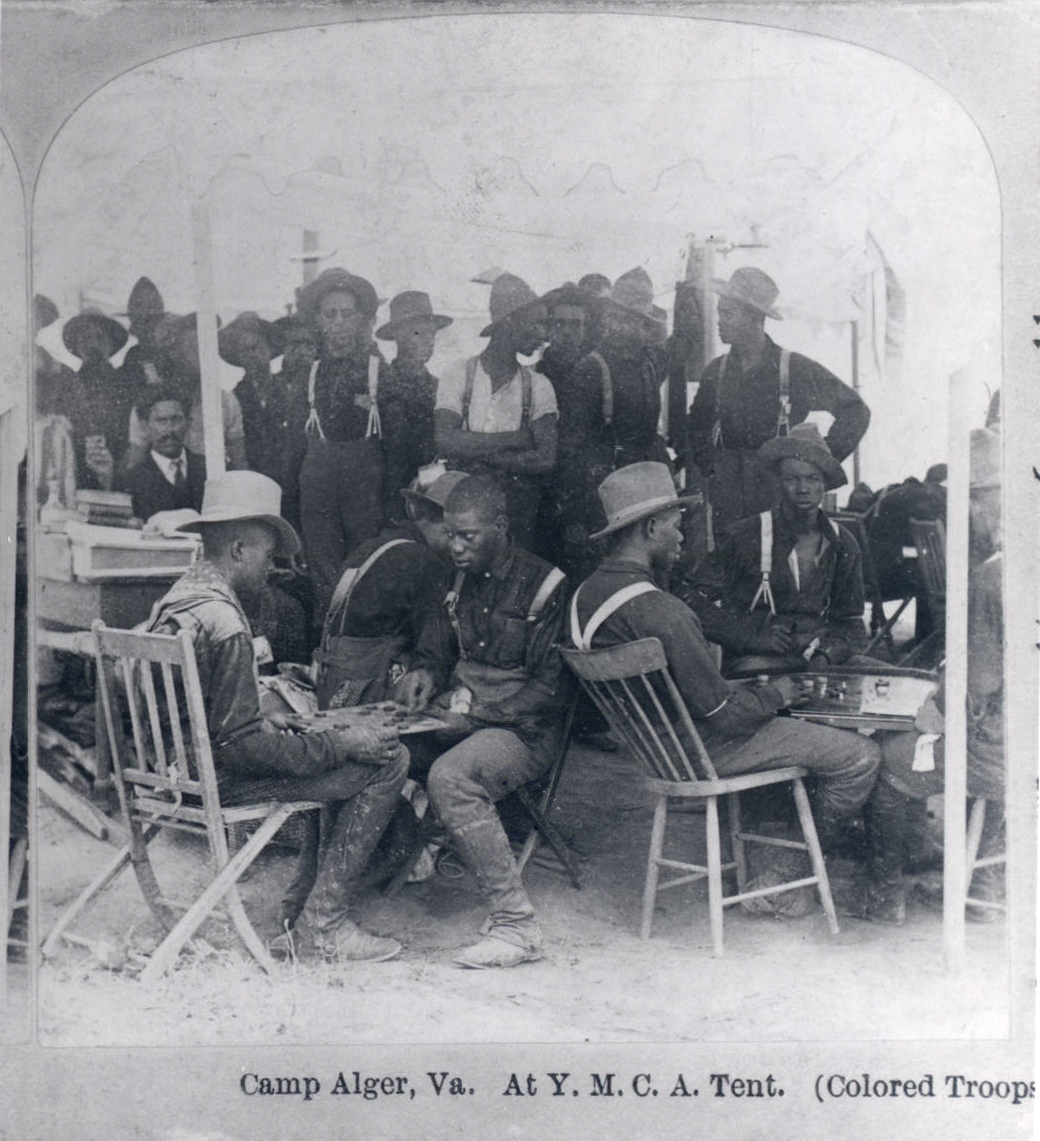

![Segregated soldiers were mobilized at Camp Alger during the Spanish American War]()

Black troops based in Virginia, c.1899.

Segregated soldiers were mobilized at Camp Alger during the Spanish American War Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017134

-

![]()

Spain turns Cuba over to the Americans.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 008418

-

![A ceremony to decorate the graves of Oregon Volunteers in Manila.]()

Battery Knoll Cemetery, Manila, 1899.

A ceremony to decorate the graves of Oregon Volunteers in Manila. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017139

Related Entries

-

![2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry]()

2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry

Relations between the United States and Spain were already strained ove…

-

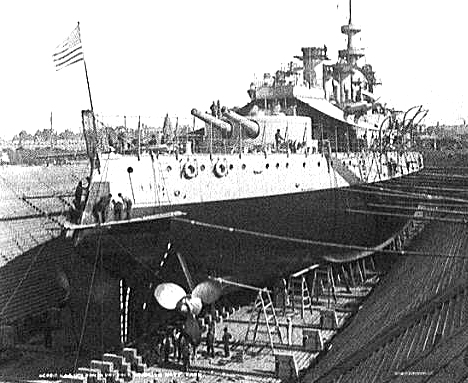

![U.S.S. Oregon]()

U.S.S. Oregon

In the years after the Civil War, the U.S. government built up its mili…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Gantenbein, Brigadier-General C. U. (compiler). The Official Records of the Oregon Volunteers in the Spanish War and Philippine Insurrection. Salem, Ore.: W.H. Leeds, State Printer, 1902.

McEnroe, Sean F. “Painting the Philippines with an American Brush: Visions of Race and National Mission among the Oregon Volunteers in the Philippine Wars of 1898 and 1899.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 104:1 (Spring 2003).

Telfer, Lt. George F. Manila Envelopes: Oregon Volunteer Lt. George F. Telfer’s Spanish –American War Letters, edited by Sara Bunnett. Portland Ore.: Oregon Historical Society, 1987.

Thompson, H.C. “War Without Medals.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 59 (1958): 293-325.