The Oregonian, the oldest newspaper in continuous production west of Salt Lake City, Utah, began as the Weekly Oregonian on December 4, 1850. Thomas J. Dryer had been recruited to start the town’s first paper because of his politics. His paper, like the future daily, was a cultivator of meaning, a tool for literacy, and a builder of reader-identity with place. Both helped attract settlers, sell lots, boost business and trade, attract investment, and establish Portland’s economic supremacy over rivals.

Dryer contributed to what became known as the “Oregon Style” of journalism, where editors satirized, ridiculed, exposed, and attacked their opposition. His feckless business methods led in 1860 to the transference of the hand-produced weekly to Dryer's manager and former printer Henry L. Pittock for unpaid wages. On February 4, 1861, Pittock inaugurated a modest six-day-a-week Morning Oregonian.

In its partisan news columns and editorials, the daily was a conservative Republican paper allied to Portland’s leading business and commercial interests and, into the 1950s, to Oregon Republican Party factions. The paper long stood for the established order, state and city growth, private and public regional investment, and efforts to establish and maintain Portland’s supremacy over regional rivals.

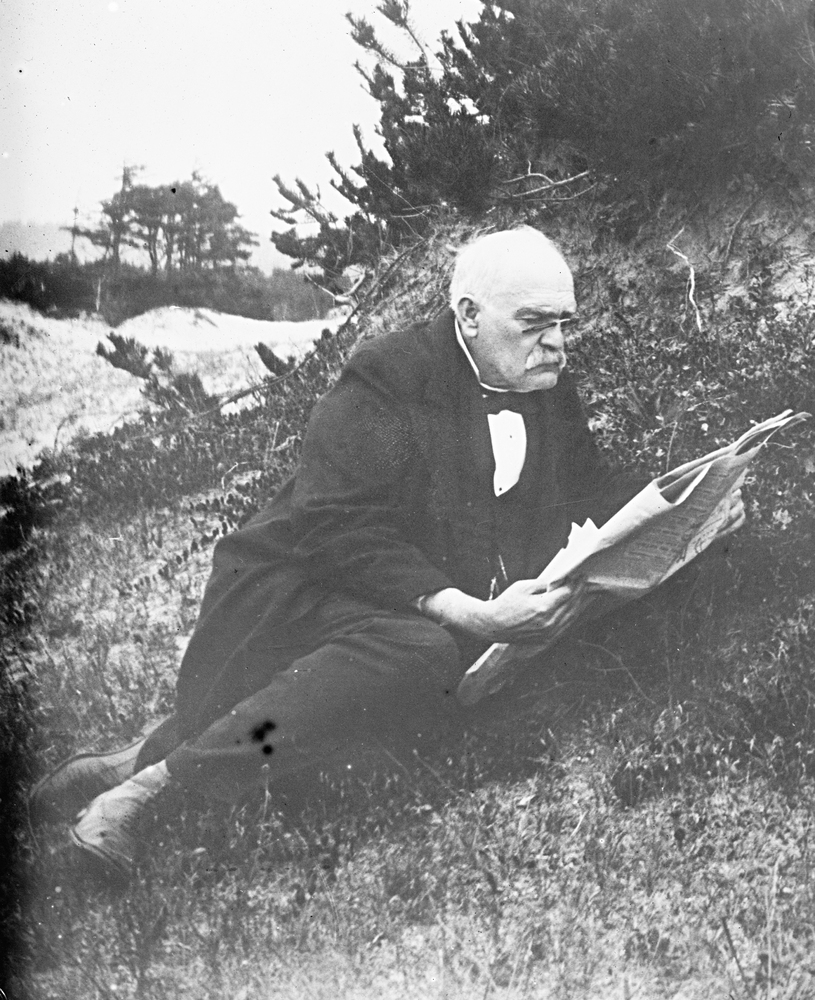

Pittock often needed extended credit and loans from wealthy businesspeople, especially Henry W. Corbett. He sold control of the paper to Corbett from 1872 to 1877, the year he opened the Evening Telegram to offset afternoon competition and reach Democrats. Oregonian profits after 1900, from lowered costs and advertising linked to a rising circulation, brought further improvements until Pittock’s death in 1919.

The daily Oregonian engaged a series of editors before settling in 1865 on Harvey W. Scott, who continued as editor until 1910 (except during Corbett's tenure) and as the minority owner after 1877. Scott oversaw most news operations, made the Oregonian the state’s “paper of record,” and established himself as a regionally influential voice on many subjects, especially politics.

Between about 1880 and 1910, the Oregonian guardedly adopted proven technologies, content, and organization. Moving toward the mass audience forged by the 1920s, the paper wanted to broaden its readership beyond people who were mainly interested in business and politics. Its something-for-everyone formula bolstered local and wire service news and introduced or augmented human-interest accounts, gossip, sports, comics, women’s features, club news, and photographs. Typesetting machines, faster presses, and typewriters lowered costs, speeded output, and enlarged editions. A feature-heavy Sunday Oregonian appeared in 1881 in response to the region’s growing population, widening transportation, and advertiser demand.

The Oregonian became a regional newspaper in the 1860s. Portlanders have always made up the largest number of subscribers and street buyers, but readership grew within a circulation area that expanded from a three-hour radius of Portland in 1881 to a twelve-hour radius in 1909. In the 1920s, the paper sent 83,000 daily and 115,000 Sunday copies throughout a 250-mile radius. Rural subscribers in three states made its weekly edition Oregon’s largest until it closed in 1922.

By the 1890s, the daily had become the state’s biggest newspaper in number of pages, audience, and workers. It was the most widely read and quoted and the most influential paper in defining significant issues for voters. Between 1880 and the late 1950s, a period when Oregon Republicans went all but unchallenged, the paper's political positions counted heavily in shaping public opinion. William McKinley’s slim 1896 presidential victory in Oregon was widely credited to the paper's support. The Oregonian, the lumber kings, and the Southern Pacific Railroad ran the state in the 1900s and 1910s, publisher E. Palmer Hoyt said, and in 1947 his daily remained “a force.”

The Oregonian partially remade itself during the Great Depression, when only its radio station, KGW (founded in 1922), remained profitable. New managers such as Hoyt proclaimed it an “Independent Republican” paper and manipulated the news less than it had to suit editorial views. The new management heightened news analyses and reviews, partly to compete with news magazines and radio. They improved design, sections, and other elements. Still, cautious reporting and a placid and noncontroversial tone endured even as war and the nation’s lengthy post-war expansion swelled the paper's editions, circulation, and coffers. Not much separated the papers of the 1940s and early 1960s. By 1972, “its role as great oracle and arbiter of the state’s politics,” wrote columnist Neal R. Pierce, had faded.

S.I. Newhouse added the Oregonian to his media empire on December 11, 1950, granting it major policy autonomy and buying it new equipment. (KGW sold independently.) Beginning in 1959, the Oregonian and the Oregon Journal withstood a bitter four-year strike that left both papers without a union. From 1961 until 1982, when the Oregon Journal ceased publication, Newhouse owned the editorially separate paper.

The steepest changes in the Oregonian’s history began in the mid-1970s. Facing the growing divide between population sectors and metropolitan newspapers, Portland’s only and the region’s biggest newspaper labored to reinvent itself. It confronted the declining attachment of suburbanites, outlying towns, women, youth, minorities, and others and tried to redirect its ability to proliferate information and entertainment channels. The paper struggled to preserve its high profits as circulation fell and advertising revenue stagnated.

The paper's managers introduced new circulation, technological, personnel, and business schemes and models. They adopted "cold type" technology, which moved production via computers to the newsroom, devastated the old craft structure, and altered newsroom roles. They promoted bright writing and investigative and explanatory journalism on government, the arts, science, business, and rural areas. News digests and entertainment and lifestyle articles took more space. The paper also invested in free papers, advertising sheets, and the Internet and experimented with design, promotion, zoned editions, and a diminished circulation area. Women and minority employment were encouraged and expanded, and staff numbers got smaller.

The Oregonian won a national reputation for quality in the 1990s and gathered in several awards, winning five Pulitzer Prizes since 1999.

-

![]()

Portland Oregonian, first issue, December 4, 1850.

Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon -

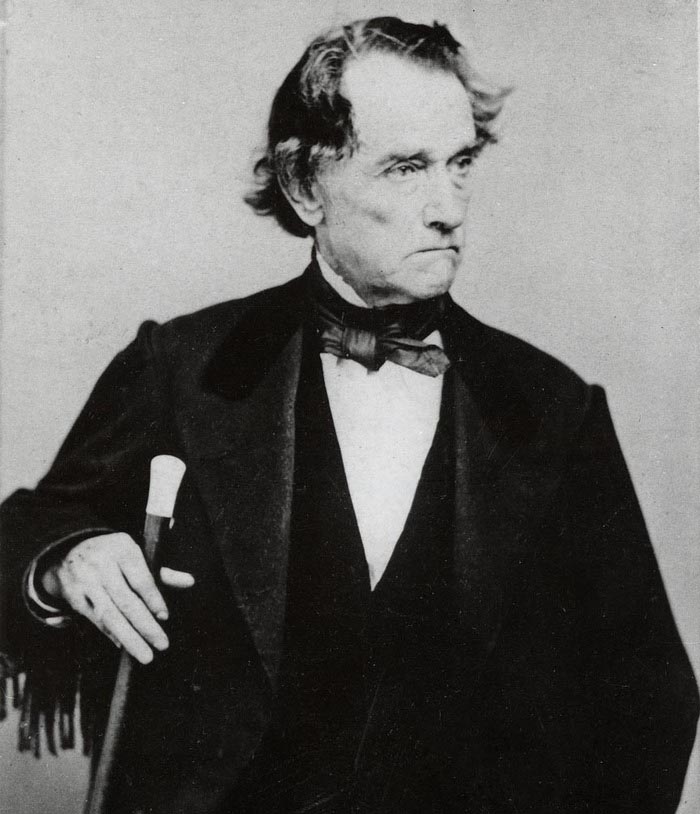

![Thomas Jefferson Dryer.]()

Dryer, Thomas Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson Dryer. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 9149

-

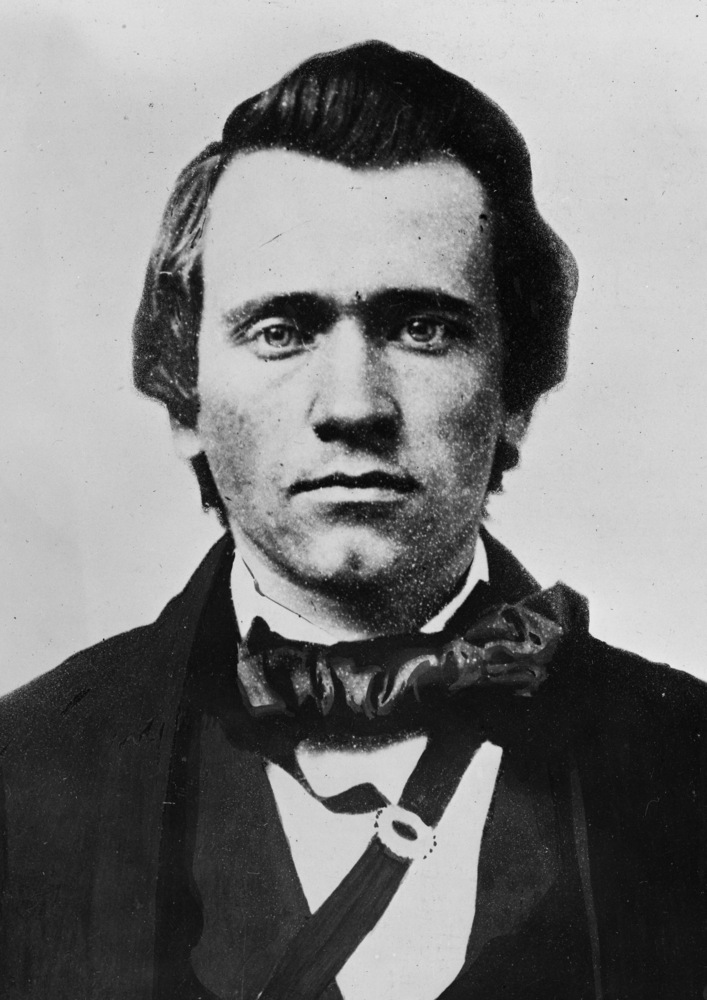

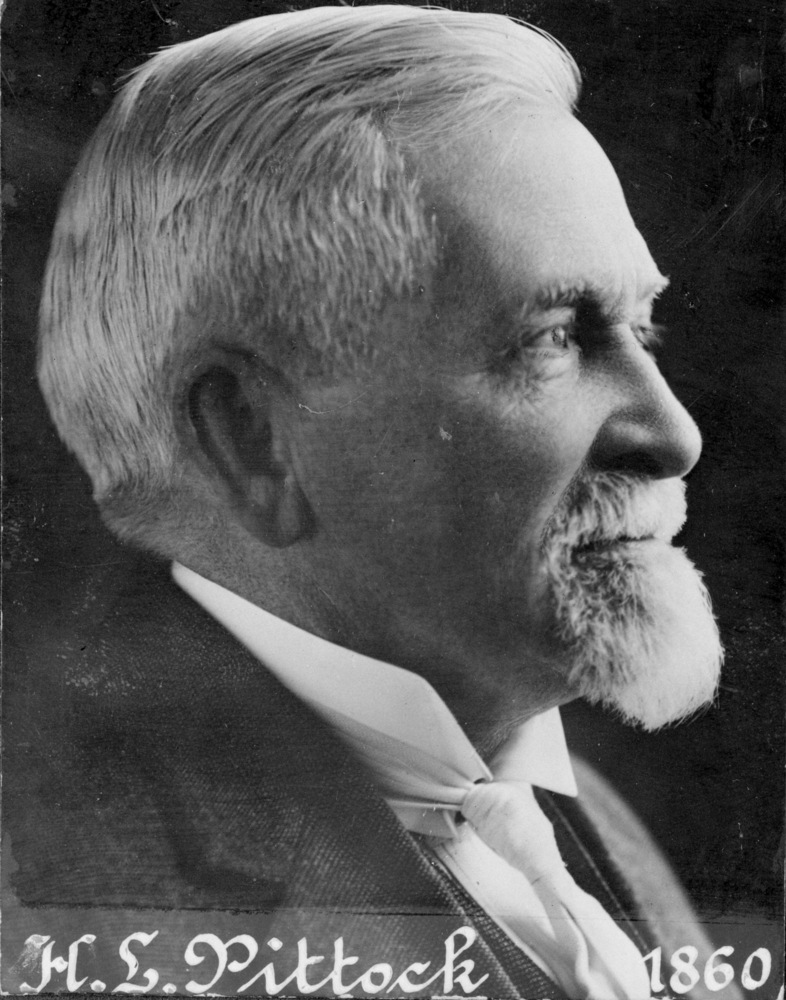

![Henry L. Pittock, about 1861.]()

Pittock, Henry, ca. 1861, bb005794.

Henry L. Pittock, about 1861. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb005794

-

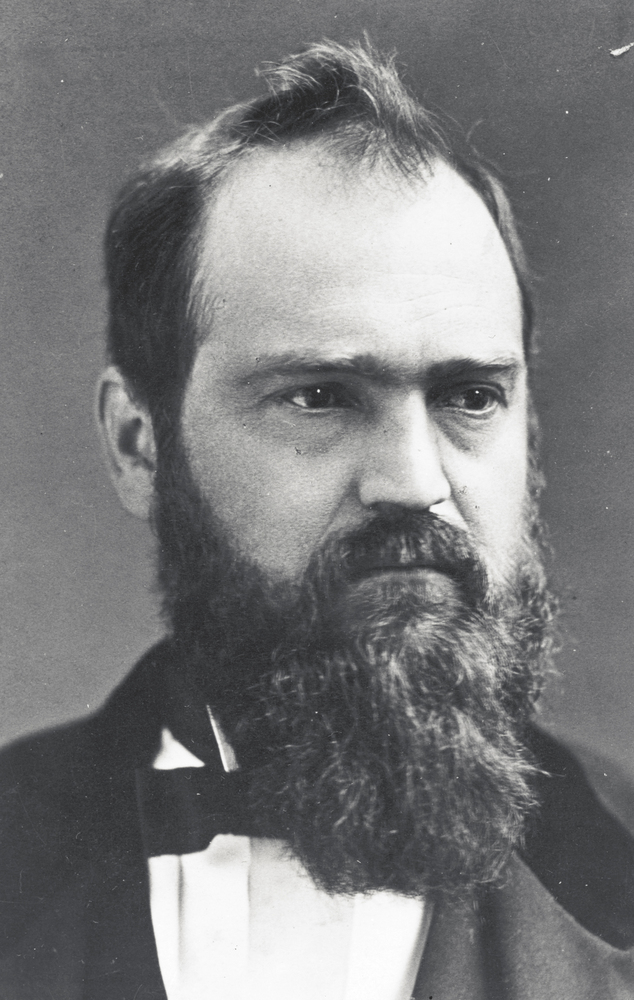

![Harvey Scott.]()

Scott, Harvey W, bb004172.

Harvey Scott. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb004172

Related Entries

-

![Harvey Scott (1838–1910)]()

Harvey Scott (1838–1910)

Harvey Whitefield Scott was the dominant editorial voice in the Pacific…

-

![Henry Lewis Pittock (1835-1919)]()

Henry Lewis Pittock (1835-1919)

Henry Lewis Pittock, longtime publisher of the Portland Oregonian, was …

-

![Jack Ohman (1960-)]()

Jack Ohman (1960-)

A widely syndicated political cartoonist, Jack Ohman has played an impo…

-

![Oregon Spectator]()

Oregon Spectator

Established in 1846, the Oregon Spectator was the first newspaper publi…

-

![Oregon Statesman]()

Oregon Statesman

Throughout its history, the Oregon Statesman has been a chronicler of O…

-

![The Portland Reporter]()

The Portland Reporter

A product of the third longest newspaper strike in the United States, t…

-

![Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)]()

Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)

Thomas J. Dryer was the first editor of the Portland Oregonian and an a…

-

![William A. Hilliard (1927-2017)]()

William A. Hilliard (1927-2017)

William A. Hilliard was the first African American editor of the Oregon…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Davis, Rob. "The Oregonian's Racist Legacy." The Oregonian. October 24, 2022.

Notson, Robert C. Making the Day Begin: The Story of the Oregonian. Portland: Oregonian, 1976.

Sterling, Donald J. Another Story: Recollections. Portland, 1999.