Situated in the far southeastern corner of Oregon, the Owyhee Canyonlands is one of the wildest regions in the contiguous United States. This scenically stunning stone labyrinth of chasms and furrowed badlands was created over eons by the erosive actions of the Owyhee River. The waters flow northward in Oregon through remote canyons, hard against the Idaho state line, emptying into the Snake River south of Ontario.

Geologically, as in most of eastern Oregon, the many volcanic features include hot springs, lava beds, craters, and cinder cones. The picturesque brick-red and golden-yellow cliffs are composed of volcanic tuff and rhyolite.

Plant communities in the canyonlands have been influenced by the nearby Great Basin Desert. Salt-scrub ecosystems have arid-adapted shrub species, including greasewood, shadscale, saltbush, and spiny hopsage. In the uplands are sweeping sagebrush-bunchgrass prairies, with patches of western juniper and mountain mahogany. Cottonwoods and quaking aspen groves trace river margins and spring-fed green meadows. During springtime's fleeting sun-showers, balsamroot, paintbrush, lupine, phlox, penstemon, globemallow, and a plentitude of other wildflowers bloom.

Several plant species, such as Owyhee clover and Packard's blazingstar, are endemics—that is, they are found nowhere else on the planet. Native vegetation zones have been distorted by overgrazing and the long-term human suppression of natural fire cycles, which periodically cleared accumulated dead entanglements. Ecological degradation worsened with the accidental introduction of Asian cheatgrass in the 1800s, along with invasive Russian thistle (tumbleweed).

Animals typical of the American West's drylands inhabit the area, including pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, coyotes, badgers, kangaroo rats, antelope squirrels, black-throated sparrows, golden eagles, and prairie falcons. And though its numbers are dwindling, the secluded terrain offers habitat for the greater sage-grouse, which is being considered for federal protection.

Sun-drenched sandy-rocky habitats are conducive to reptiles, including horned lizards, leopard lizards, collared lizards, striped whipsnakes, and rattlesnakes. The Owyhee drainage is the only place in Oregon where the diminutive ground snake has been recorded. Although secretive and rarely seen, its bright red-orange and black dorsal pattern is eye-catching. This is also one of the few locations in the state where the Woodhouse's toad lives. After dark, along with bats and burrowing owls, prowling kit foxes and giant desert hairy scorpions can sometimes be glimpsed in the beam of a flashlight.

Humans have occupied the Owyhee Canyonlands at least since the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age. Little is known about the first hunter-gatherers to live there some 10,000 years or more ago, but the few remaining traces are intriguing. A boulder along a remote stretch of the Owyhee has an etched petroglyph that resembles an elephant, perhaps a portrayal of the wooly mammoth. Over many centuries, the cultures of these aboriginal bands gradually diverged into distinct tribes that are now identifiable as Northern Paiute, Bannock, and Shoshone.

North West Company fur trappers led by Scottish-Canadian Donald McKenzie during the winter of 1818-1819 were the first non-Native people to enter the area. Three Hawaiian members of the group were dispatched to explore, but they never returned from the canyon. The river was named in their honor, using the home-island Polynesian pronunciation of "Owyhee."

During the 1860s, when white settlers began establishing cattle ranches, small communities, and stagecoach way-stations on Native homelands, conflicts were inevitable. The U.S. Army established several military camps to quell the conflict. Later in the 1870s, immigrant Basque sheepherders brought herds to the bunchgrass prairies, sometimes sparking range wars with cattlemen.

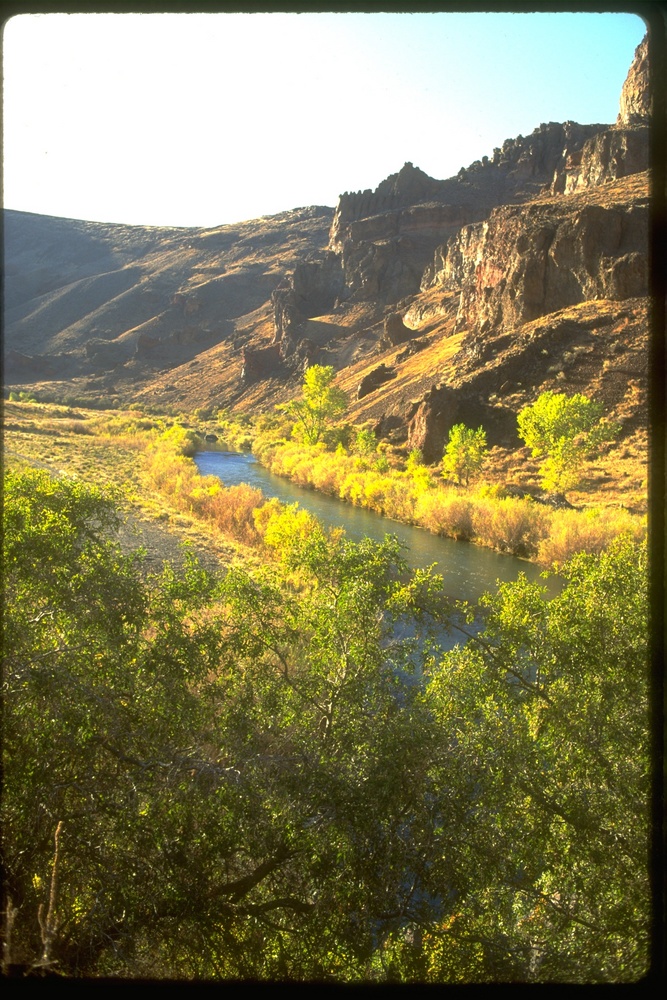

Much of the Owyhee River is designated a Wild and Scenic River. Many stretches of the river feature narrow slot canyons with thousand-foot sheer stone walls, and the entire drainage is characterized by a maze of side-canyons and gulches. Except where Highway 95 crosses the river, only a few mostly unmarked dirt roads penetrate the heart of the canyonlands. A high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle, outfitted with extra gas and water, is required to venture into the rugged backcountry. Rain can quickly transform the dirt tracks into slippery mud, a dangerous situation for travelers in the summer.

Access into the canyonlands by boat is possible by way of fifty-mile-long Lake Owyhee, where the river is impounded behind the Owyhee Dam. Rafting trips are common along the free-flowing upper segments during spring season's high water. At the area's periphery, good gravel roads lead to the stone spires of Leslie Gulch, south of Adrian, and the dramatic Pillars of Rome formations near the tiny riverside community of Rome.

Comprising two-million acres of relatively intact ecosystems, the Owyhee Canyonlands has been identified by conservationists as one of the nation's most significant natural areas. The Oregon Natural Desert Association and a coalition of partners are advocating wilderness protection for extensive sections of these landscapes.

-

![Pillars of Rome formations, Owyhee River Canyon]()

Pillars of Rome formations, Owyhee River Canyon.

Pillars of Rome formations, Owyhee River Canyon Courtesy Alan St. John

-

![Dusting of snow in Leslie Gulch; Owyhee Canyonlands]()

Dusting of snow in Leslie Gulch; Owyhee Canyonlands.

Dusting of snow in Leslie Gulch; Owyhee Canyonlands Courtesy Alan St. John

-

![The Pillars of Rome formations; Owyhee Canyonlands]()

The Pillars of Rome formations; Owyhee Canyonlands.

The Pillars of Rome formations; Owyhee Canyonlands Courtesy Alan St. John

-

![Bunchgrass prairie, with a dusting of November snow, in the Owyhee uplands]()

Bunchgrass prairie, with a dusting of November snow, in the Owyhee uplands .

Bunchgrass prairie, with a dusting of November snow, in the Owyhee uplands Courtesy Alan St. John

-

![Twilight in Leslie Gulch; Owyhee Canyonlands]()

Twilight in Leslie Gulch; Owyhee Canyonlands.

Twilight in Leslie Gulch; Owyhee Canyonlands Courtesy Alan St. John

Related Entries

-

![Basques]()

Basques

The first Basques to Oregon arrived in the late 1880s. These Euskalduna…

-

![Hawaiians in the Oregon Country]()

Hawaiians in the Oregon Country

Native Hawaiians were among the earliest outsiders in present-day Orego…

-

![Owyhee River]()

Owyhee River

The Owyhee River, in the southeastern corner of Oregon, is a 280-mile-l…

-

![Rattlesnakes in Oregon]()

Rattlesnakes in Oregon

The rattlesnake is the only dangerously venomous reptile in Oregon. Amo…

-

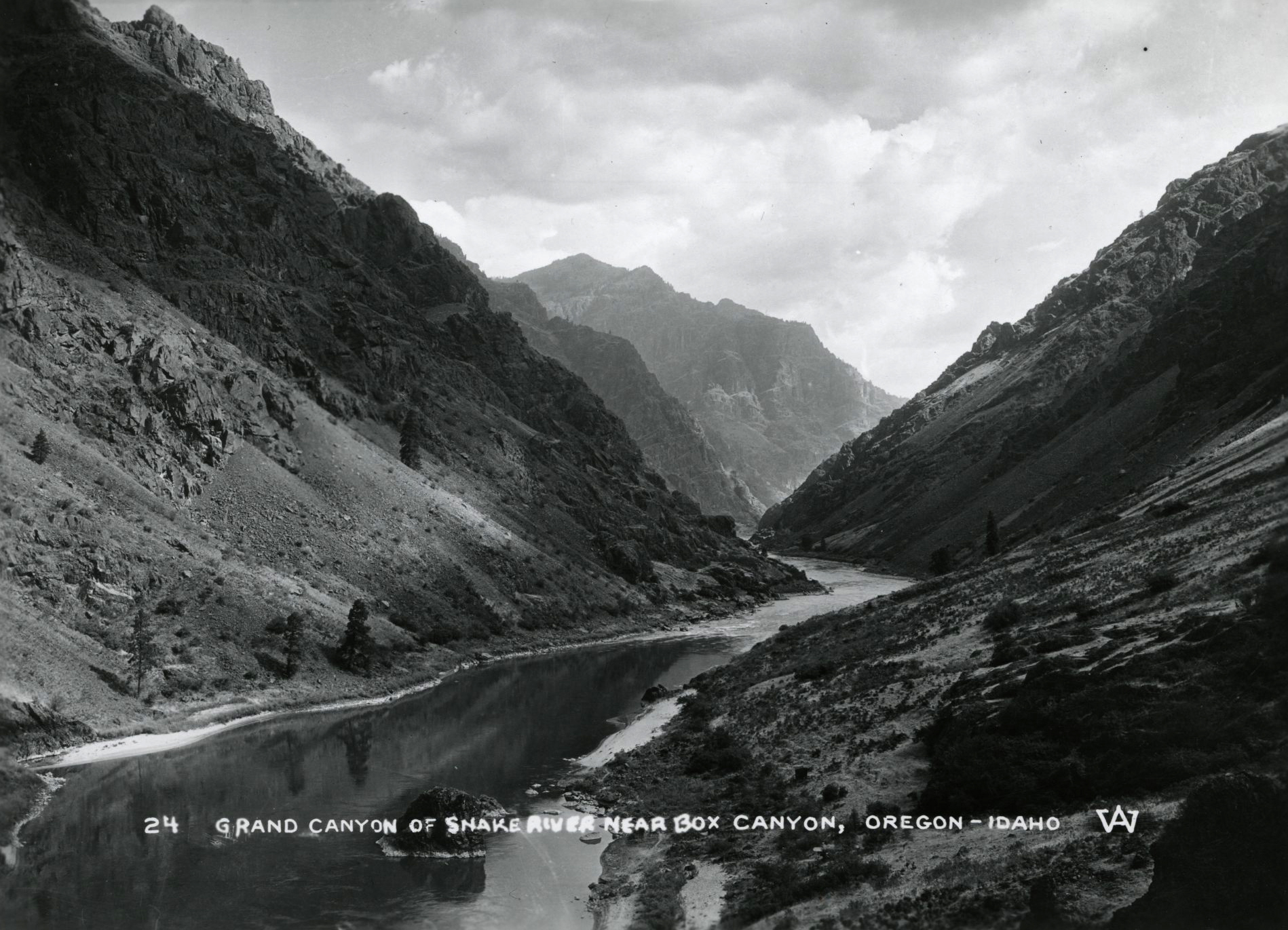

![Snake River]()

Snake River

The Snake River has its headwaters at an elevation of 8,200 feet on the…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bishop, Ellen Morris. In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2003.

Hanley, Mike. Owyhee Trails: The West's Forgotten Corner. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1974.

St. John, Alan. Oregon's Dry Side: Exploring East of the Cascade Crest. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2007.