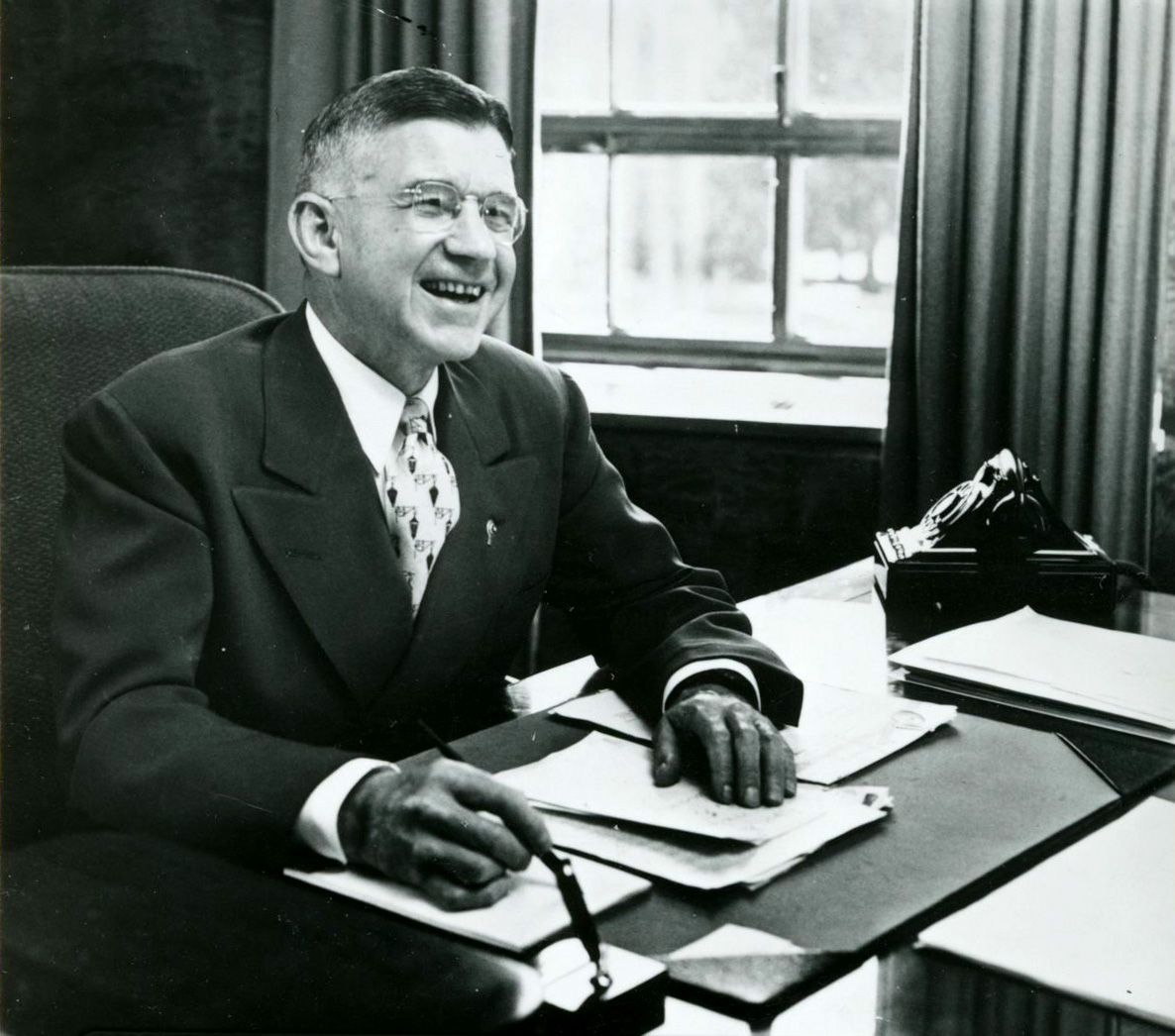

Owen Murphy Panner was a lawyer and federal judge in Oregon from the mid-twentieth century into the first decades of the twenty-first. He was the longtime attorney for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and served as a U.S. District Court of Oregon judge for thirty-eight years.

Panner was born in Chicago on July 28, 1924, but he grew up in Oklahoma, first in Whizbang and then in Shawnee. His father, Elmer Panner, was a geologist and engineer who worked in the oil industry, and his mother, Irene Murphy Panner, was a homemaker who cared for Owen and two younger daughters. Owen’s father passed on his love of golf to his son, who began playing the game at age six and eventually became an expert.

Living in a city and state with racial segregation and a large Native population left indelible impressions on Panner. While Black and white students attended separate schools, both Indians and whites attended Shawnee High School, where he was a student, and Panner had Indian friends, dated an Indian girl, and caddied alongside Indians at the local golf club.

World War II interrupted Panner’s undergraduate studies at the University of Oklahoma, and he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1943. He was assigned to the infantry, where he rose through the ranks to first lieutenant, supervising the loading of troops and cargo on transport ships across the Atlantic. After a whirlwind courtship in Los Angeles, he married Agnes Gilbert, a second lieutenant in the Nursing Corps; they would have three children.

After the war, Panner attended law school at the University of Oklahoma on a golf scholarship. He later remembered Ada Sipuel, an African American student who was denied entrance to the law school in 1946. When Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma (1948), brought by the NAACP, resulted in her admission, Panner and other law students welcomed her and made sure she sat with the rest of the class rather than in the cordoned-off seat the school provided.

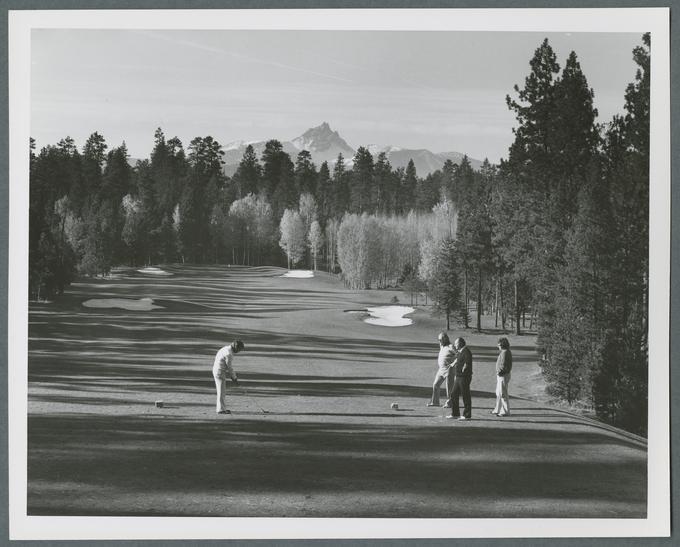

After receiving a law degree in 1949, Panner went west to find a place to raise his family and begin his legal career. New Mexico appealed to him, but he remembered a friend’s uncle, Judge Claude McCulloch, praising the beauty of central Oregon. Encountering Bend on a bluebird day with the Three Sisters rising in the distance, he knew he had found home. He worked for a car dealership while preparing for the Oregon Bar exam, which he passed in 1950.

Panner became the trial lawyer for a small law practice headed by Duncan McKay. When the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs wanted to hire legal counsel, they turned to Panner, who some Warm Springs members knew from his days selling cars. In 1955, Panner became the attorney for the Tribes, a relationship that lasted for twenty-five years. He provided counsel on the construction of Kah-Nee-Ta Resort, the development of the Warm Springs Forest Products Industries, the construction of Round Butte and Pelton Dams on the Deschutes River, and the defense of Native fishing rights on the Columbia River. One complex matter resolved with Panner’s guidance was the Tribes’ recovery of 79,000 acres of land known as the McQuinn Strip. A faulty 1871 survey had been disputed for years, and Panner brokered an agreement among the Tribes, Oregon senators and congressmen, the U.S. Forest Service, cattlemen, and timber interests to restore the land to the Warm Springs people.

Panner was also involved in Bend’s civic life, serving on the boards of the Lions Club, Boy Scouts, Central Oregon Community College, Chamber of Commerce, Oregon Bend Golf Club, and Central Oregon Arabian Horse Club. He helped found the High Desert Museum in 1982 and was the attorney for the Mt. Bachelor Ski Resort from its beginning. In 1968, Owen and Agnes Panner bought land outside Black Butte and began breeding and showing Arabian horses.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter nominated Panner to the U.S. District Court of Oregon. For the next thirty-eight years, he handled many high-profile cases. In Far West Federal Bank, S.B. v. Director, Office of Thrift Supervision (1990), he issued temporary restraining orders preventing federal regulators from taking over Far West Federal Savings & Loan, one of thousands of institutions that failed during the savings-and-loan debacle in the 1980s and 1990s. In United States v. Camp, Panner set a precedent by ruling that it was legal to grant a federal wiretap to a judicial position, such as attorney general, rather than in the name of the individual holding that position.

In March 1994, Judge Panner issued a temporary restraining order delaying a disciplinary hearing for figure skater Tonya Harding by the U.S. Figure Skating Association, which had ordered the hearing based on the attack of Nancy Kerrigan by Harding’s ex-husband Jeff Gilooly. Harding was found guilty of participating in the assault on Kerrigan, stripped of her 1994 championship title, and banned for life from participating in USFSA events.

Panner was considered “a trial lawyer’s trial judge” and was respected by criminal defense lawyers, particularly for his ruling in 2004 that federal sentencing guidelines were unconstitutional because they violated the separation-of-powers doctrine in United States v. Detwiler (2004). The Supreme Court upheld the guidelines in a series of decisions in 2004–2007. In his oral history, Panner remembered that his father told him to “use your brains and don’t rely on conventional wisdom.” That advice informed his judicial practice of doing what he believed was right, making proceedings run efficiently, encouraging succinct writing, and fostering collegiality.

A supporter and mentor for women lawyers, Panner supported and helped advance his female colleagues during a time when few men would. He once chastised a male lawyer who addressed a woman attorney by her first name. When a colleague asked for a recommendation for a lawyer, the judge shared the name of a woman who was “the best law clerk he’d ever had.”

Panner was voted Trial Lawyer of the Year in 1973 and was a member of the exclusive American College of Trial Lawyers. In 1983, he formed the first Oregon chapter of the American Inn of Court, which is named for him. He served on the board of the U.S. District Court of Oregon Historical Society and received its Lifetime of Service Award in 2008. He also served on the Oregon Historical Society Board of Trustees from 1981 to 1997, the last two years as president. In 1989, he married Nancy Hanson, whose teenage daughter he considered his fourth child.

Beginning in 1992, Panner took senior status and moved his chambers to the James A. Redden Federal Courthouse in Medford. Working only slightly less than full time, he eventually slowed to working only two days a week until a few weeks before his death on December 19, 2018.

-

![]()

Owen Panner.

Courtesy Oregon U.S. District Court Historical Society

-

![]()

U.S. WWII draft card for Owen Panner.

Courtesy National Archives & Records Administration, National Archives in St. Louis, MO

-

![]()

Photo of Owen Panner (bottom left) golfing in the University of Oklahoma yearbook, 1950.

Courtesy U.S., School Yearbooks, 1880-2012, University of Oklahoma, 1950

-

![]()

Owen and Nancy Panner a the U.S. District Court Historical Society Picnic, 2003.

Courtesy Owen Schmidt

-

![Panner is 7th from right with hat.]()

Owen Panner with Warm Springs Tribal leaders, 2009.

Panner is 7th from right with hat. Courtesy Jennifer Newton

Related Entries

-

![Black Butte Ranch]()

Black Butte Ranch

Black Butte Ranch is an 1,800-acre private resort community surrounded …

-

![James Douglas McKay (1893-1959)]()

James Douglas McKay (1893-1959)

Douglas McKay, a conservative Republican, was governor of Oregon from 1…

-

Three Sisters Wilderness

The Three Sisters Wilderness area in the central Cascade Mountains has …

-

![Tonya Harding (1970- )]()

Tonya Harding (1970- )

Tonya Harding was a United States champion figure skater who competed i…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Brown, Anna J., and Mark Clarke. “From Whizbang to the Federal Bench and the 'Best Saddle in the Arena.''' Oregon Benchmarks (Spring/Summer 2019).

Buan, Caroline M., editor. The First Duty: A History of the U.S. District Court of Oregon. Portland: U.S. District Court of Oregon Historical Society, 1993.

Panner, Owen Murphy. U.S. District Court Judge. Interview with Michael O’Rourke from November 24, 1994-May 15, 2001. SR 1241 Oregon Historical Society Davies Family Research Library, Portland.

Van Meter, Heather. “Judge Owen Panner: From Whizbang to the Bench.” Oregon Benchmarks (Spring 2003). https://usdchs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2003-2-spring-Oregon-Benchmarks.pdf