Walter Cornelius Reynolds was the first African American graduate of the University of Oregon Medical School (now Oregon Health & Science University) and one of only two Black doctors practicing in Portland in the mid-twentieth century. A clinical assistant professor of family planning at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Reynolds focused much of his effort on improving his own community. He was a firm believer in universal healthcare and an outspoken proponent of cultural competency. Throughout his life, he was aware and appreciative of the community support he received.

Reynolds was born in northeast Portland on March 24, 1920. His parents, Phil and Elise Reynolds, had come to Oregon from Decatur, Georgia, and Phil Reynolds worked as a red-cap for the Northern Pacific Terminal Co. at Union Station for over thirty-five years. Walter attended Jefferson High School, where he developed an interest in science and sports, particularly basketball. His older brother Jack, who earned a master’s degree in physics from the University of Washington, was Reynolds’s inspiration to pursue a career in medicine. When Walter’s high school guidance counselor told him it would be a waste of time to study medicine because there were “no Negro physicians,” Reynolds was angry, but not deterred. Portlanders at this time supported racist housing codes that restricted where Blacks could live, crosses were being burned on front lawns, and restaurants remained segregated — these conditions would shape Reynolds’s life and career.

Reynolds planned to take a year off between high school and college—his family could not support two sons attending college at the same time—but he changed his mind and made his way to Eugene, where he worked to pay his tuition and room and board at the University of Oregon. He also wanted to play basketball, but the coach told him it was too difficult to find a place for a Black player to stay when they had away games. Nevertheless, Reynolds made the team, although he was only allowed to play at home games. He would eventually play with the Medics, the medical school team, while attending the University of Oregon Medical School (UOMS), now OHSU. He graduated from the University of Oregon with a Bachelor of Science degree in biology in 1943.

Reynolds also had an interest in flying. He took a course at Swan Island Airport in Portland and later got his private pilot’s license. He tried to sign up for the Army Air Corps but was rejected because of vision requirements, so he applied to medical school instead. After completing his first year at UOMS, Reynolds enlisted in the U.S. Army and served in the 93rd Infantry Regiment from 1943 to 1946, first as an engineer at Fort Lewis and then at Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia. His final posting was to the South Pacific, but the war ended as he was in transit, and he served out his tour in the Philippines.

Returning to UOMS in 1946, Reynolds graduated in 1949. After completing an internship at Broadlawn Community Hospital in Des Moines, Iowa, “on the auspices of the Air Force,” he repaid the Air Force through military service as a medic, attending the Randolph Field School of Aviation Medicine for training and then serving at Alaska’s Eielson Air Force Base as a base surgeon until 1952. He completed a residency at San Mateo Community Hospital and returned to Portland to begin his medical practice in 1953.

Reynolds set up his clinic at Weidler Street and North Williams Avenue in Albina, taking over for Robert Joyner, another Black physician. Joyner was moving to Seattle, which left Reynolds and DeNorval Unthank as the only two Black doctors practicing in the city. Reynolds would eventually be on the staff of Emanuel, Providence, Good Samaritan, St. Vincent, and Holladay Park hospitals.

Reynolds’s philosophy was to treat anyone who came to his clinic, regardless of background, race, gender, or ability to pay. He cared for Portland’s large Romani-speaking community, who most doctors refused to treat. As a result, his income was, in his own words, “not very good.” His approach, however, coupled with having one of the earliest computerized medical offices in the city, meant that he was the largest recipient of welfare funds in the region. Years later, around 1985, Reynolds moved his office farther north and renamed it the Phil Reynolds Clinic in honor of his father.

As president of Emanuel Hospital staff from 1971 to 1972, Reynolds made community connections to build a new hospital. In 1974, he began serving as the first director of the Emanuel Hospital Family Practice Resident Training Medical Clinic, a federally funded, three-year residency program. As an educator, he gave talks on cultural competency to medical students and helped recruit students of color to OHSU. Reynolds worked with the NAACP, the Urban League (where he was president in 1959), the Oregon Community Foundation, the Boy Scouts, and the City Club and was on Mayor Terry Schrunk’s urban renewal committee and the Governor’s Task Force for Education (1972). He was also president of OHSU’s School of Medicine Alumni Association, and it was reported that he donated as much as $150 a month to the Portland Black Panthers to support community work.

Reynolds was a charter fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a diplomat of the American Board of Family Practice. He was named a distinguished alumnus of Jefferson High in 1997, and he and his family started a scholarship program in honor of Phil Reynolds that offered support to minority students. In 2007, OHSU named one of its aerial tram cars “Walt” in his honor.

Reynolds and his wife, Mildred Eleanor Squires, who died in 1991, had six children. Walter Reynolds died on November 17, 2020, at the age of one hundred.

-

![]()

Walter Reynolds.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 563

-

![]()

Walter Reynolds and Portland Mayor Terry Schrunk, 1960.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Walter Reynolds (left) and an unidentified man, possible Urban League meeting, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

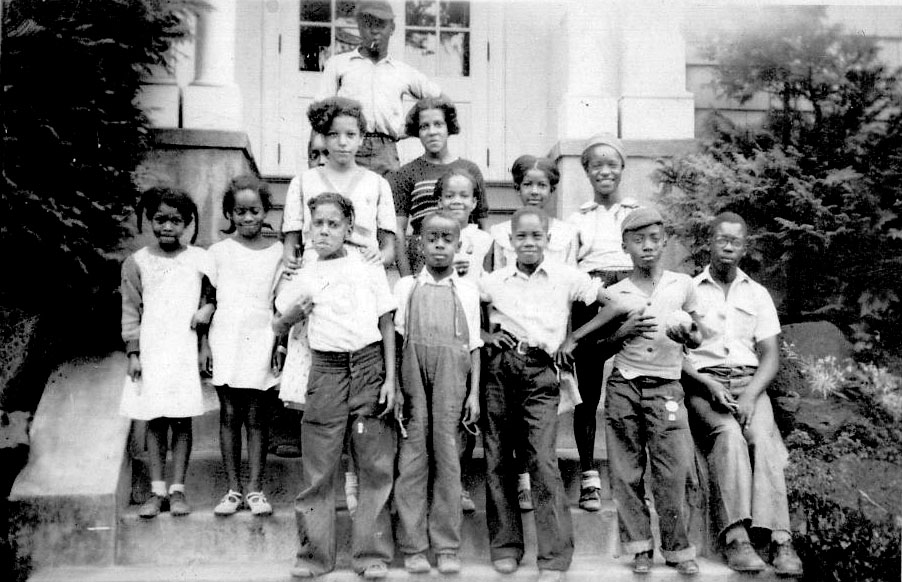

Walter Reynolds.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 563

-

![]()

Phil and Elise Reynolds, 1960.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 563

Related Entries

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)]()

DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)

In 1929, Portland was a city deeply divided. Its small population of Af…

-

![Housing Authority of Portland]()

Housing Authority of Portland

The Housing Authority of Portland was created in 1941 in response to th…

-

![Nathalie McDowell Johnson (1959-)]()

Nathalie McDowell Johnson (1959-)

Dr. Nathalie McDowell Johnson, a dancer and physician, moved to Oregon …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Barnett, Erin Hoover. “Centenarian’s Wisdom Remains a Lesson Today.” OHSU News, March 24, 2020.

Burke, Lucas N. N., and J. L. Jeffries. The Portland Black Panthers: Empowering Albina and Remaking a City. 1st edition. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016.

Oregon Health Sciences University School of Medicine Alumni Association. Medical Focus, Winter 1991. Archival Publications, Oregon Health & Science University Historical Collections & Archives.

Reynolds, Walter C. Interview by Ralph Crawshaw. May 23, 2007. History of Medicine in Oregon project, Oregon Health & Science University Historical Collections & Archives. Portland, Ore.

Zimmerman, Jim. Memories of Champions: The Medics, 1942-1945. Archival Publications. Oregon Health & Science University Historical Collections & Archives, 1995.