Clyde Rice was eighty-one years old when he published his first book in 1984. Before writing A Heaven in the Eye, he had not thought seriously about writing, but the book won the Western States Book Award for creative nonfiction, judged that year by Robert Penn Warren. USA Today called it one of the ten best books of the year. By 1992, Rice’s reputation had earned him the Stewart H. Holbrook Literary Legacy Award from Literary Arts for “significant contributions that have enriched Oregon’s literary community.”

Rice was born in Portland in 1903. His mother was a Christian Science practitioner who hoped her son would pursue a profession, and his father was a business owner who encouraged his son to become a salesman. But he had other interests and tried his hand at many jobs.

Working for the U.S. Forest Service in the summer as a sixteen-year-old, he thought he had found his life’s work as a woodsman; but he was falsely accused of insubordination, damaging equipment, and wrecking a bunkhouse and was dismissed from his dream job. “I had lost my first love,” he wrote in A Heaven in the Eye. He returned to high school and spent more and more time in the art department. He soon fancied himself a painter but was expelled from school for displaying a risqué poster announcing a wrestling meet and for writing and publishing an essay against prohibition. Subsequently, he convinced his parents to let him attend the Portland Art Museum School for two years, where he and fellow students Charles Heaney and Kinzu Furiya studied with Harry Wentz. At the school, Rice also met Evelyn Nordstrom, known as Nordi.

Rice had difficulties getting jobs because of his lack of experience and his looks. “My face was aflame with great running sores,” he wrote. “I was an ugly sight.” After Rice and Nordi married and moved to San Francisco, he worked for a time for his father, who had set up a branch of business there in manufacturing food flavors. On weekends, he studied with artist Maynard Dixon, and Nordi became a popular model for Dixon and art school students.

Believing that he “hadn’t much to offer beyond being a fair draftsman who seriously studied art,” Rice decided that he needed to “work out of doors…with my hands and my back.” He became a deckhand on ferries in San Francisco Bay and held various other jobs, both in California and on his return to Oregon. He failed at all of them, either tiring of the work or getting fired for his bad temper.

While recuperating from a knee operation, Rice took up writing to combat idleness. Knowing that he needed help with his writing, he called Reed College on a whim in 1981 and asked if someone there would be willing to look over his work. Adjunct writer-in-residence Gary Miranda read and edited Rice’s manuscript and recommended it to James Anderson at Breitenbush Publications, who had published Miranda’s work. A Heaven in the Eye appeared in 1984, and Miranda was Rice’s editor for the next two books.

When Rice wrote, the words flowed generously, “with this strange memory of mine,” and with compelling honesty. Rice to write his books.He explained his purpose in A Heaven in the Eye: “I guess the center of this…autobiography of mine, is to find out if my life has really been worthwhile; to find, by extension, if we as a people are worth our salt, if life was as rich as it seemed or if romanticism fit me with invisible glasses.” In A Heaven in the Eye, which covers the years from 1918 to 1934, Rice takes Nordi to San Francisco, then returns with her and their son Bunky on a Joad-like trip. The sequel, Nordi’s Gift (1990), begins with Rice, at age thirty-one, returning to his native western Oregon with his family.

In Oregon, Rice developed an attraction to his wife’s niece Virginia, and she became the object of his affection and the inextricable ingredient of a complex love triangle that resulted in his eventual divorce from Nordi and marriage to Virginia, seventeen years his junior. Anchored in their small farm and rammed-earth house on the Clackamas River, Rice drew on forty-five years of memories to capture sentiments familiar to Oregonian readers. Between his two long books, he wrote a short autobiographical novel, Night Freight (1987), about hopping trains through the Siskiyou Mountains with hoboes during the Depression. It outsold his first book.

Rice died in 1998 at the age of ninety-four. His contribution to Oregon literature was in creative nonfiction that emphasizes place and personal reflection, in the tradition of Barry Lopez and William Kittredge, earning national acclaim by focusing his narratives on Oregon as a place of both a beginning and an end. What made him remarkable, Gary Miranda wrote in his eulogy, was "his tenacity, his boundless curiosity...his honesty...his amazing energy and his sheer love of life." The Friends of Clyde Rice promote his legacy and maintain a writers’ retreat on Rice’s ten-acre farm on the Clackamas River.

-

![]()

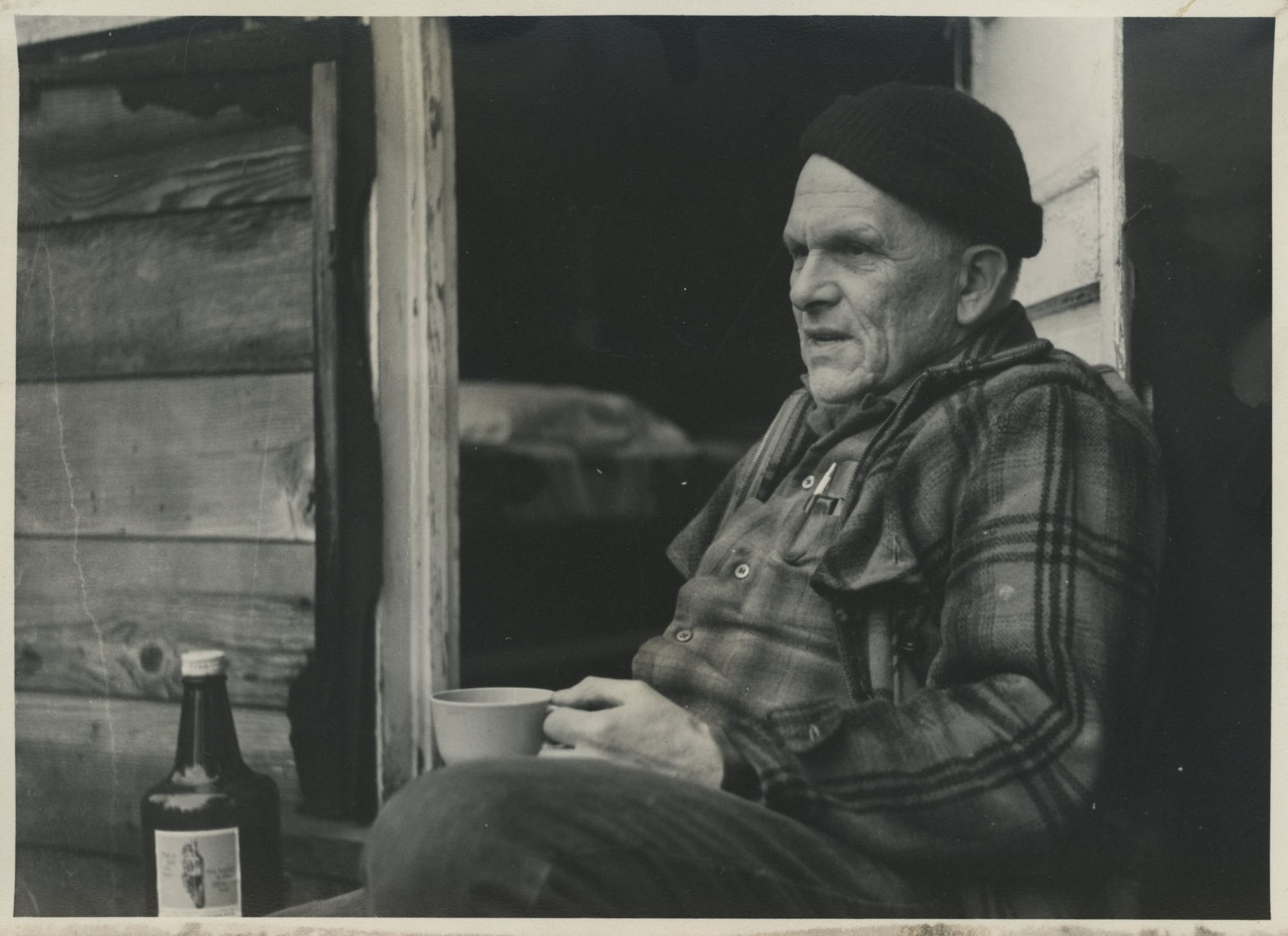

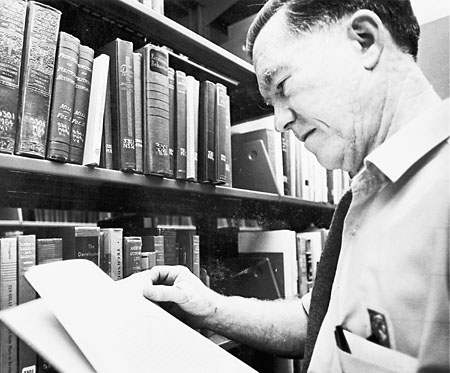

Clyde Rice.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 900

-

![]()

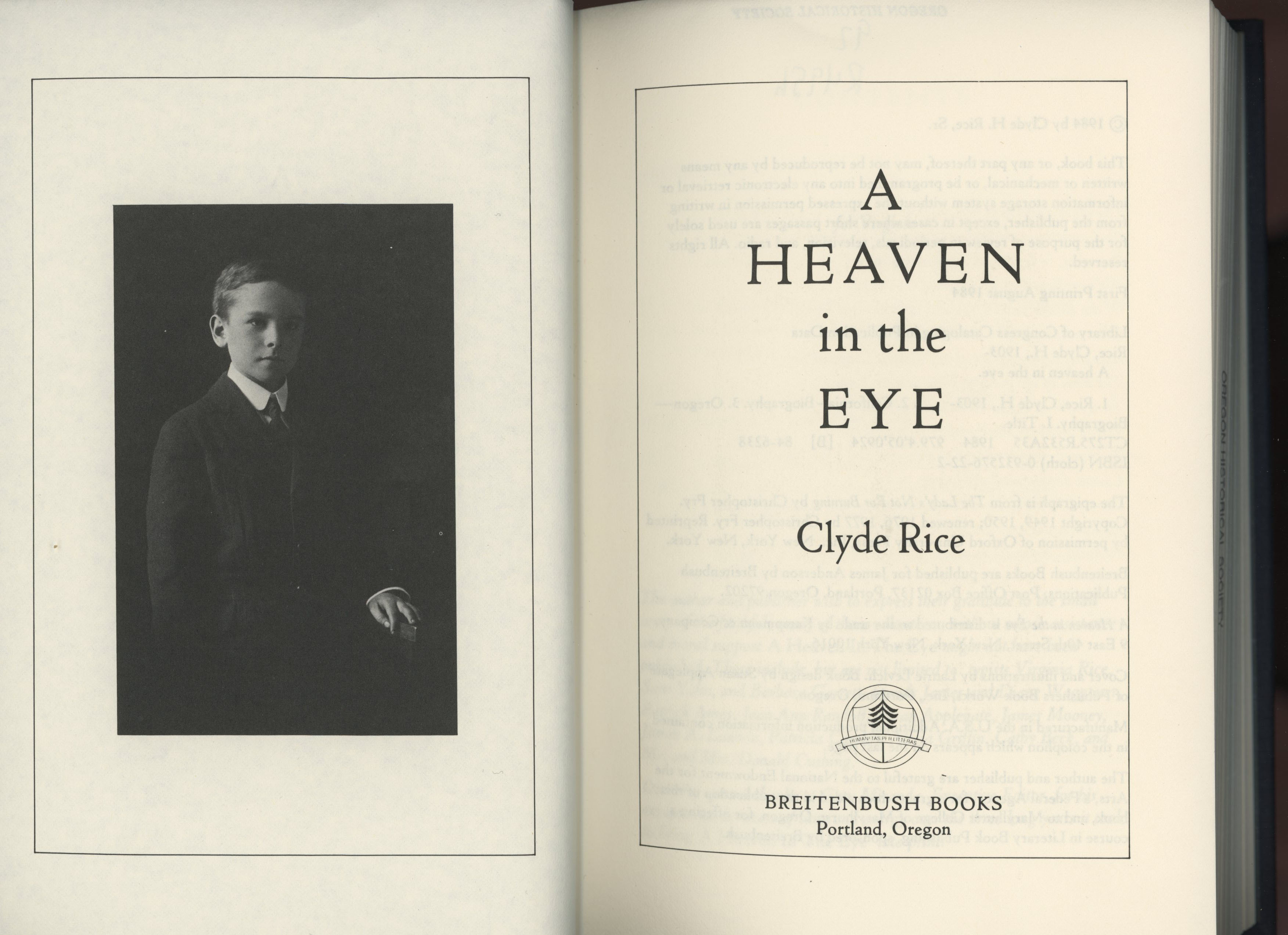

A Heaven in the Eye, title page.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 92 R495h

-

![]()

Heaven in the Eye, table of contents, with chapter titles.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 92 R495h

-

![]()

Chapter heading from Nordi's Gift.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 92 R495n

Related Entries

-

![Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)]()

Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)

Born and raised in rural and small-town Oregon, Harold Lenoir Davis was…

-

![Ken Kesey (1935-2001)]()

Ken Kesey (1935-2001)

A farm boy from the Willamette Valley, Ken Kesey brought an earthy, ind…

-

![Portland Art Museum School]()

Portland Art Museum School

In October 1909, the Portland Art Association (PAA) opened its school, …

-

![William Stafford (1914-1993)]()

William Stafford (1914-1993)

William Stafford, one of America’s most widely read poets, was born in …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lyon, Thomas J., ed. Updating the Literary West. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1997.

Rice, Clyde H. A Heaven in the Eye. Portland, Ore.: Breitenbush Publications. 1984.

_____. Night Freight. Portland, Ore.: Breitenbush Books. 1987.

_____. Nordi’s Gift. Portland, Ore.: Breitenbush Books, 1990.