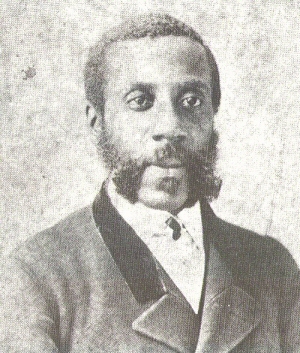

Identified by the Oregonian as the “Fred[erick] Douglass of Oregon,” George P. Riley was a passionate advocate for equal rights and a leading figure in Portland's early African American community. With inspirational oratory, breadth of knowledge, and organizational skills, Riley helped advance political and economic opportunities for many.

Born in Boston on March 29, 1833, George Putnam Riley learned about courageous activism from his parents William and Elizabeth (Cook) Riley, free persons of color and abolitionists. William owned a clothing store, and the couple contributed money and effort to the abolitionist cause, including the work of William Lloyd Garrison. Elizabeth was active in the Boston Female Antislavery Society, the African-American Female Intelligence Society, and the Colored Citizens of Boston. In 1850, the year after William's death, she helped fugitive slave Shadrach Minkins escape by hiding him in her attic.

Without schooling themselves, George's parents sought education for their children—those by Elizabeth's marriage to James Jackson in 1813 and then her marriage to William Riley in 1829. When George was only a few months old, his half-brother James Jackson Jr. died at age six and was memorialized by his teacher, Susan Paul. George Riley attended public school, but colleges were closed to him because he was Black. He attended antislavery mass meetings in Boston, where he met abolitionist leader Wendell Phillips and worked in the law office of Benjamin F. Butler, later a Civil War general. To secure a living income, he became a barber.

In his early twenties, Riley followed the lure of California gold and journeyed by sea to the West Coast. While in San Francisco, he joined an 1858 convention of free Blacks who opposed California's discriminatory laws, and he accepted the invitation of James Douglas, governor of the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, to settle in Victoria. Over time, about eight hundred Black settlers emigrated to Victoria, with some, like Riley, seeking gold on the Fraser River. For most, increased racial prejudice diminished the promise of a better life. At an 1864 public meeting in Victoria, resolutions were accepted from a committee that included Riley and Abner Hunt Francis, previously a resident of Portland. They argued that "the English colonists of Vancouver Island, in utter disregard of English law and English customs, are making a vigorous effort to place the badge of complexional distinction upon the subjects of a darker hue."

After the Civil War, Riley visited Washington Territory and Oregon before returning to Massachusetts, where he resumed barbering and gave lectures about the Pacific Coast. He married Harriet Elizabeth Gordon of New Brunswick, Canada, on April 30, 1866, at Chelsea, Massachusetts; their one child, Bonita Louise, was born the next year.

Drawn to the West and undeterred by Oregon's Black exclusion laws, Riley arrived in Portland by early 1869; his family came later. Portland's population of about eight thousand included forty-one African American men and twenty-one women. For several months, Riley was a barber with James H. Givins at Humboldt Hair Dressing, Shaving and Bathing Saloon on Front Street.

On December 11, 1869, with Riley as president, the Workingmen's Joint Stock Association of Portland (WJSA) filed for incorporation in Oregon, with capital stock of $50,000 (about $958,000 in 2021 dollars). Riley and fourteen other Portlanders—twelve Black men, two Black women, and one white man—had invested in real estate to be divided proportionately. Their occupations included bootblack, barber, boot and shoemaker, domestic servant, waiter, steward, cook, general jobber, laborer, whitewasher/calsominer, plasterer, messenger, porter, and landlady.

Washington Territory permitted Blacks to purchase land. In 1869, on behalf of WJSA, Riley paid $2,000 for twelve acres in Seattle. Two years later, the WJSA acquired fifteen more acres. Legally known as Riley's Addition, the property became part of Seattle's Beacon Hill district. In 1870, Riley purchased sixty-seven acres in Tacoma for the WJSA. The Alliance Addition, which was the basis for Tacoma's African American community, was labeled “N–––r Tract," and ownership of the land was in litigation for decades. Most WJSA members paid their taxes and held their land in Washington, and some sold at a profit. Others lost their property because of high taxes and assessments, and the property of those who died without heirs became entangled in lawsuits. A few owners moved to their Washington properties, where they lived out their lives.

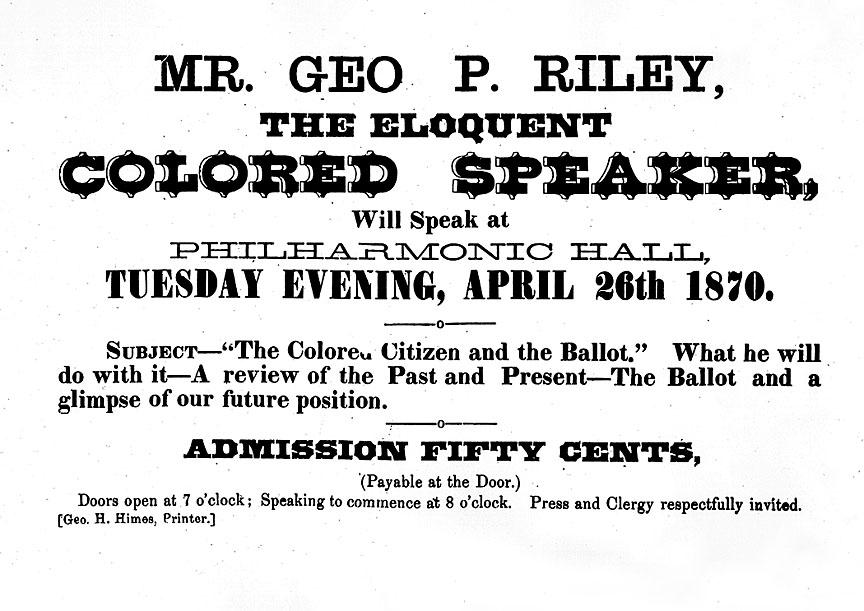

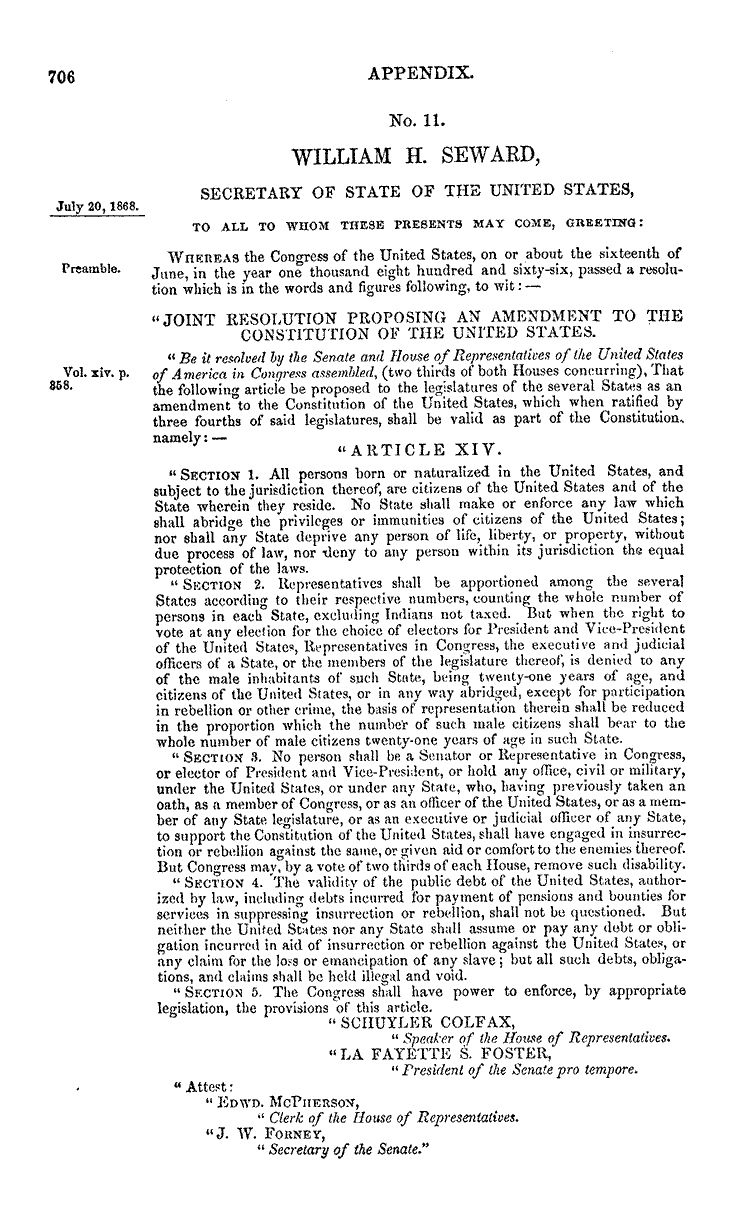

Riley had exceptional rhetorical, organizational, and political skills. He was orator for the 1870 New Year's Day Emancipation Celebration in Salem; spoke that April at Portland's Ratification Jubilee, the celebration of the 15th Amendment; and gave a talk at Portland's Philharmonic Hall on “The Colored Citizen and the Ballot.” In May 1870, he became president of Portland's Sumner Union Club, a political organization that endorsed the Union Republican Party of Oregon. In 1873, when Riley presided at a state convention supporting congressional action for a civil rights bill, the Statesman described him as a person with "considerable celebrity as an educated man and eloquent speaker."

Riley addressed Black, white, and mixed audiences and frequently appeared with speakers such as former Governor Addison Gibbs, Senators Joseph Dolph and John Mitchell, Harvey W. Scott of the Oregonian, Rev. T. L. Eliot of the Unitarian Church, and woman suffrage leaders Abigail Scott Duniway and Mary Anna Cooke Thompson. Whether he was addressing the Workingmen's Association, the Oregon State Woman Suffrage Association, the Colored Citizens of Portland, the First A.M.E. Zion Church, Portland's Colored Immigration Aid Society, or Republican rallies, audiences welcomed Riley as the “renowned colored orator.”

Recognized for his character and abilities, Riley was selected in 1877 for jury duty in Portland. The San Francisco Elevator reported: "For the first time in the history of Oregon, a colored man was drawn as a Grand Juror in the U.S. District Court. George P. Riley had the honor of being that individual. The world is moving."

Barbering remained Riley's trade, but he also worked at Portland's U.S. Customs House from about 1873 to 1877, during Harvey Scott's tenure as Collector of Customs. At Customs, he worked with Abigail Duniway's husband, Benjamin, and earned $1,200 a year as a porter and messenger. At about this time, he lived with his family and three boarders at 128 College Street.

In 1887, Riley moved to his property in the Alliance Addition, where he spent the last eighteen years of his life. He was the orator for Tacoma's Annual Emancipation Day celebrations, joined other Blacks to organize a mining company near Issaquah, and was unrelenting in efforts to resolve legal disputes surrounding WJSA's properties in Tacoma. In 1904, he was elected delegate from the 10th precinct of the 3rd Ward for Tacoma's Republican Convention.

Harriet Riley died in 1896, and George died nine years later, on October 1, 1905. Both were interred at Tacoma Cemetery.

During his 1871 lecture for Portland's Young Men's Christian Association, Riley defined the highest virtues "of true manhood" and applied them to Toussaint L'Ouverture (1742–1803), the former slave and military leader of Saint-Domingo (later Haiti). In his own life, Riley not only established a remarkable record of accomplishment but clearly lived with those same virtues of "courage, spirit of liberty and persistence."

-

![]()

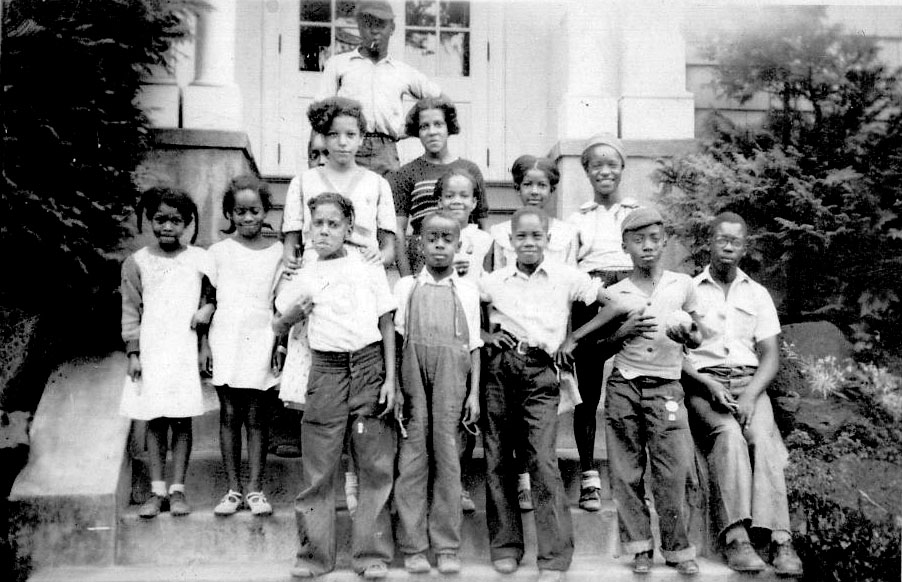

George Putnam Riley.

-

![]()

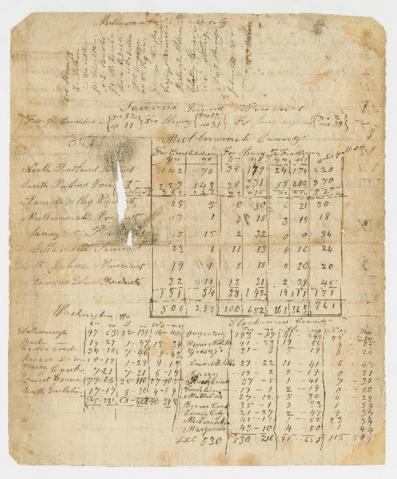

Broadside for a lecture by George P. Riley, 1870.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHi24847

Related Entries

-

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![15th Amendment]()

15th Amendment

Civil War Reconstruction arguably culminated with the Fifteenth Amendme…

-

![Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)]()

Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)

A. H. Francis, a free Black, was a merchant and activist who in 1851 op…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Creation of Washington Territory, 1853]()

Creation of Washington Territory, 1853

On August 14, 1848, Congress created Oregon Territory, a vast stretch o…

-

![First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church]()

First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

First African Methodist Episcopal Zion is Portland's oldest African Ame…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Advertisement. "Grand Ratification Jubilee." Morning Oreonian, April 5, 1870. p. 2.

Advertisement. "Mr. Geo. P. Riley, The Eloquent Colored Speaker." Morning Oregonian, April 19, 1870, p. 2. (See also the Oregon History Project online for broadside by printer George H. Himes for this lecture by Riley.)

Advertisement. "Grant and Wilson!" [Republican Rally] Morning Oregonian, November 4, 1872, p. 2.

Advertisement. "To the Public, Humboldt Hair Dressing, Shaving and Bathing Saloon." Morning Oregonian, April 10, 1869. p.2.

Advertisement. "Sumner Union Club Rally." Morning Oregonian, May 18, 1870. p. 2.

"Attack on Title: Seattle Residence District Is Involved." Morning Oregonian, October 9, 1904. p. 6.

Baumgartner, Kabria. In Pusuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Oregon to the Legislative Assembly. Sixth Regular Sesion, September 1870. Salem, Ore: W. A. McPherson, State Printer, 1870.

Brown, Lois. "Out of the Mouths of Babes: The Abolitionist Campaign of Susan Paul and the Juvenile Choir of Boston." New England Quarterly 75:1 (March 2002): 52-79.

"City. Colored I.A.S. [Immimgration Aid Society]." Morning Oregonian, December 31, 1879. p. 3.

"CIty. The Lecture." Morning Oregonian, February 8, 1871. p. 3.

Collison, Gary. Shadrach Minkins: From Fugitive Slave to CItizen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

"The Colored Martyr's Anniversary: 106th Anniversary of the Death of Crispus Attucks, Colored Patriot." The New Northwest, March 17, 1876. p. 2.

"A Colored National Convention." Weekly Oregon Statesman, November 18, 1873. p. 2.

"Correction." Weekly Oregon Statesman, December 13, 1869. p. 3.

"Emancipation Day." The Daily Statesman and Unionist, January 1, 1870. p. 3.

"First Charge," The Liberator, November 15, 1884. p. 4.

Fried, R. (2018, January 14) Elizabeth Riley (1791-1855). Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/riley-elizabeth-1791-1855/

"Funeral of George P. Riley." The Tacoma Daily News, October 4, 1905. p. 8.

"George P. Riley Dead." The Seattle Republican, October 6, 1905. p. 8.

"A Grand Rally." Morning Oregonian, June 6, 1880. p. 3.

"Grant and WIlson: Grand and Enthusiastic Republican Rally at the Court House Last Evening." Morning Oregonian, November 5, 1872. p. 3.

Horton, James Oliver. "Generations of Protest: Black Families and Social Reform in Ante-Bellum Boston," New England Quarterly 49:2 (June 1976): 242-256.

"Letter from Oregon," the San Francisco Elevator, March 31, 1877, p. 2.

Lowe, Turkiya. (2018, January 11) George Putnam Riley (1833-1905). Retrieved from https:///www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/riley-george-putnam-1833-1905/

McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon 1788-1940. Portland, Ore.: The Georgian Press, 1980.

Moreland, Kimberly Stowers. African Americans of Portland. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

Mumford, Esther Hall. Calabash: A Guide to the HIstory, Culture & Art of African Americians in Seattle and King County, Washington. Seattle: Ananse Press, 1993.

Nokes, R. Gregory. Breaking Chains: Slavery on Trial in the Oregon Territory. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013.

"Opening of 'Nigger Tract' Was a Stupendous Undertaking." The Tacoma Times, April 20, 1904. p. 4.

"Oregon State Woman Suffrage Association--Second Annual Convention" The New Northwest, February 19, 1875. p. 2.

"Passed into History [OSWSA Convention]," The New Northwest, November 17, 1881. p. 4.

"Passing of a Pioneer; George Putnam Riley Is Dead at Tacoma." The Morning Oregonian, October 2, 1905. p. 4.

Paul, Susan. Memoir of James Jackson, The Attentive and Obedient Scholar, Who Died in Boston, October 31, 1833, Aged Six Years and Eleven Months, By His Teacher, Miss Susan Paul. Boston: James Loring, 1835. Rpt., Lois Brown, Ed. Memoir of James Jackson. Cambridge: Harvard Unniversity Press, 2000.

"Pierce County." Morning Oregonian, March 31, 1898. p. 3.

Pilton, James William, "Negro Settlement in British Columbia, 1856-1871," M.A. Thesis, History, The University of British Columbia, September 1951. Appendix F, Resolutions Published in the Pacific Appeal after the Election of January 1864, p. 228.

"Pioneer Colored Man Passes Away." The Tacoma Daily Ledger, October 5, 1905. p. 7.

"Presentation and Farewell Meeting." The Liberator, July 13, 1849. p. 2.

"The Ratification; The Woman Suffrage Resolution Endorsed." The New Northwest, October 28, 1880. p. 1.

Reese, Gary Fuller, ed. Who We Are: An Informal HIstory of Tacoma's Black Community before World War I. Tacoma: The Tacoma Public LIbrary, 1992. pp. 26-27.

Richard K. Keith. "Unwelcome Settlers: Black and Mulatto Oregon Pioneers." Part II, Oregon HIstorical Quarterly 84:2 (Summer 1983): 173-205.

The United States Treasury Register, Containing a List of All Persons Employed in the Treasury Department. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875. p. 138.

"Washington Notes," Morning Oregonian, March 21, 1898. p. 3.

"Well Known Colored Resident Is Dead." The Tacoma Daily News, October 2, 1905. p. 2.

"Woman Suffrage Convention; Platform for the Coming Election in June Adopted." Morning Oregonian, February 14, 1884. p. 3.