In the early morning hours of August 7, 1959, a parked truck—loaded with two tons of dynamite and over four tons of ammonium nitrate—caught fire outside a supply store on the edge of downtown Roseburg. The resulting explosion, known locally as The Blast, sent a ball of flame and a mushroom cloud of smoke over two thousand feet into the air. A Roseburg policeman described the explosion as looking like "an A-bomb"; a pilot flying over the vicinity at the time actually thought there was a Soviet attack. The Roseburg explosion attracted national attention and resulted in stricter explosives-transport safety regulations and enforcement by the Interstate Commerce Commission.

The Blast killed 14 people and injured over 120 others. Some people were blown through windows and one guest at the Umpqua Hotel was hurled through his room's closed door and into the corridor. A number of buildings were leveled, and many others within the thirty-block disaster area had to be demolished because of structural damage. The Blast broke windows up to seven miles away and was reportedly heard as far away as Eugene.

The night before, George Rutherford, the driver of the truck, had parked in front of the three-story Dent-Gerretsen Contractors Supply building where a security guard was supposed to be on duty. He had checked his load, locked the truck doors, and left for a room at the Umpqua Hotel. His employer, Pacific Powder Company of Tenino, Washington, had been worried about nighttime theft and had told Rutherford not to leave the truck overnight at the explosive-storage depot outside Roseburg, as was customary.

At about midnight, a fire of unknown origin broke out in the Dent-Gerretsen building. The sign on the truck warning of explosives did not catch the notice of the firemen and police on the scene until it was too late.

At 1:14 in the morning, Rutherford, awakened by the sirens and flames, rushed towards his truck. The truck's load exploded when he was a half-block away, blowing him back and knocking him unconscious. Among the dead were a fireman, policeman, residents of nearby apartment buildings (including a four-year-old girl), and several passersby and onlookers.

The Blast, which left a crater twenty feet deep and over fifty feet in diameter, leveled eight blocksof Roseburg's commercial core. Contractors later reported that newer pumice-block structures (that is, those made of concrete) fared worse than older brick buildings. For two weeks, over a hundred Oregon National Guard troops patrolled the blast area—called "ground zero" by Mayor Harlow Jacklin and others—so the coroner and other investigators could recover human remains and inspect structural damage.

According to the Oregonian's on-the scene reporter, civil-defense authorities from "throughout the country" took special interest in Roseburg's efforts following the explosion, noting the small-scale similarity to a nuclear attack. In addition, like many small American cities at the time, Roseburg had had no disaster-response plan. The Blast caused Roseburg and other communities to prepare such plans.

Although a lawsuit brought to light Pacific Powder's poor safety record, neither the company nor Rutherford was found liable. After the Roseburg Blast, federal regulations and state laws would more tightly regulate both public and private carriers of explosives.

-

![]()

Tipped police car parked near the blast; policeman died, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 59085

-

![]()

Area near the the crater, Roseburg.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015182

-

![]()

Damage by Roseburg blast, August 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 62412

-

![]()

Crater created by the truck explosion (location of truck).

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015174

-

![]()

Aerial of Roseburg blast.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba013196

-

![]()

Roseburg blast, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015171

-

![]()

Workers hose down a feed and grain store, Roseburg.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015173

-

![]()

Roseburg explosion, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015181

-

![]()

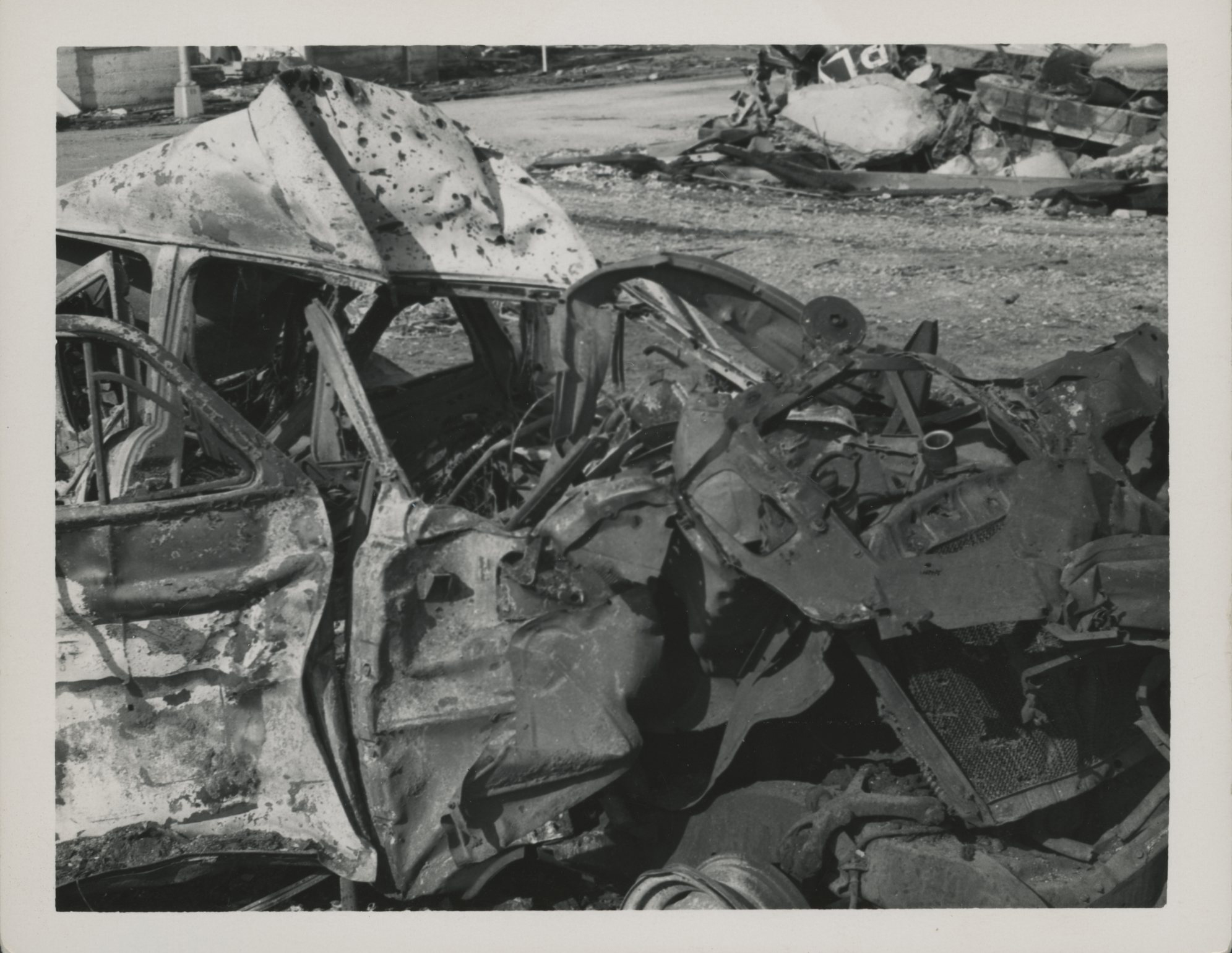

Car destroyed by blast, Roseburg.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015170

-

![]()

Remains of a cafe, Roseburg.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015172

-

![]()

Melted coke bottles after the Roseburg blast, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba015175

-

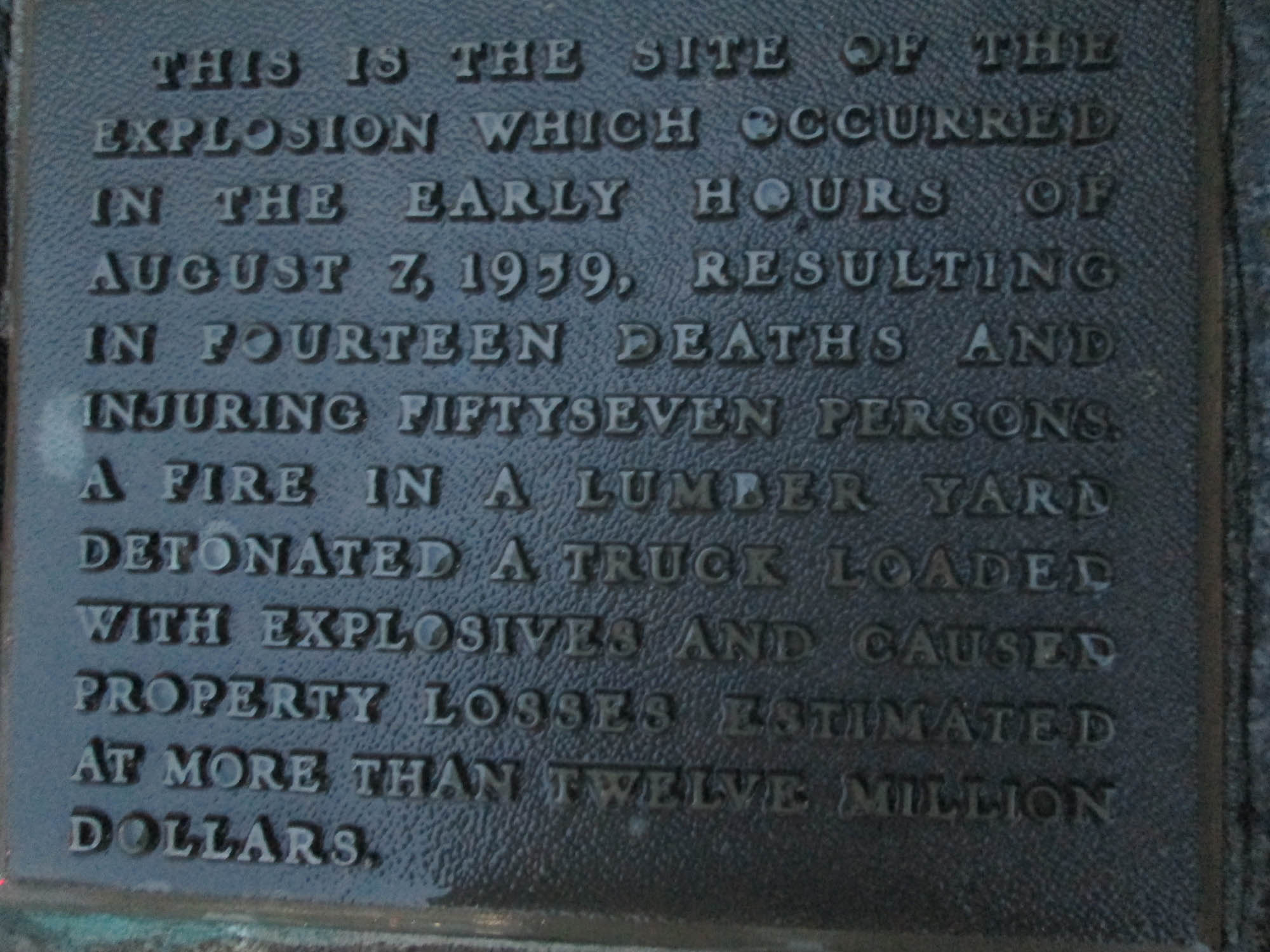

Roseburg blast commemorative plaque.

Roseburg blast commemorative plaque Courtesy Ulrich Hardt

-

Roseburg Blast exhibit, Douglas County Museum.

Roseburg Blast exhibit, Douglas County Museum Courtesy Ulrich Hardt

-

Roseburg Blast exhibit, Douglas County Museum.

Roseburg Blast exhibit, Douglas County Museum Courtesy Ulrich Hardt

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Oberst, Greg and Lisa Wojna. Disasters of the Northwest: Stories of Courage and Chaos. Edmonton, Alberta: Folkore Publishing, 2010.

Banel, Feliks. "Blast Devastated Roseburg, Oregon, 58 years ago." My Northwest, August 2, 2017. Includes audio interview with Bill Brubaker, who covered the blast on local radio station KRXL.