Sacagawea was a member of the Agaideka (Lemhi) Shoshone, who lived in the upper Salmon River Basin in present-day Idaho. In about 1800, she was kidnapped by members of the Hidatsa tribe and taken to their homeland in the Knife River Valley, near present-day Stanton, North Dakota. A few years later, she was traded to or purchased by a French Canadian trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau. She was pregnant with his child when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark arrived at the Knife River villages in November 1804, on their mission to find a feasible route to the Pacific Ocean.

Sacagawea’s son, Jean Baptiste, was born on February 11, 1805. He would become the youngest member of the Corps of Discovery when his parents took on the role of interpreters for the expedition and left Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805. Sacagawea’s presence, according to Clark’s journal, also assured Native tribes that the expedition was not a war party.

While accompanying the expedition, Sacagawea no doubt performed many of the same tasks she would have undertaken in the Knife River villages, including dressing hides, making moccasins, and foraging for roots and berries. She supplemented the men’s diet with traditional foods that might have helped prevent scurvy and perhaps even starvation. Surely for a group of men traveling “on their stomachs,” her ability to gather food meant that their diet was varied and somewhat more palatable than it would have been otherwise.

Near present-day Dillon, Montana, Sacagawea boosted the men’s morale when she identified Beaverhead Rock and assured them that they were near her homeland and birth tribe. At one point during the journey, Sacagawea was able to “read” or identify the moccasin tracks of a tribe in the vicinity. On the return trip, in the spring of 1806 near present-day Bozeman, Montana, she acted as Clark’s “pilot” when she pointed out the way her people crossed today’s Bozeman Pass, from the Gallatin Valley to the upper Yellowstone River.

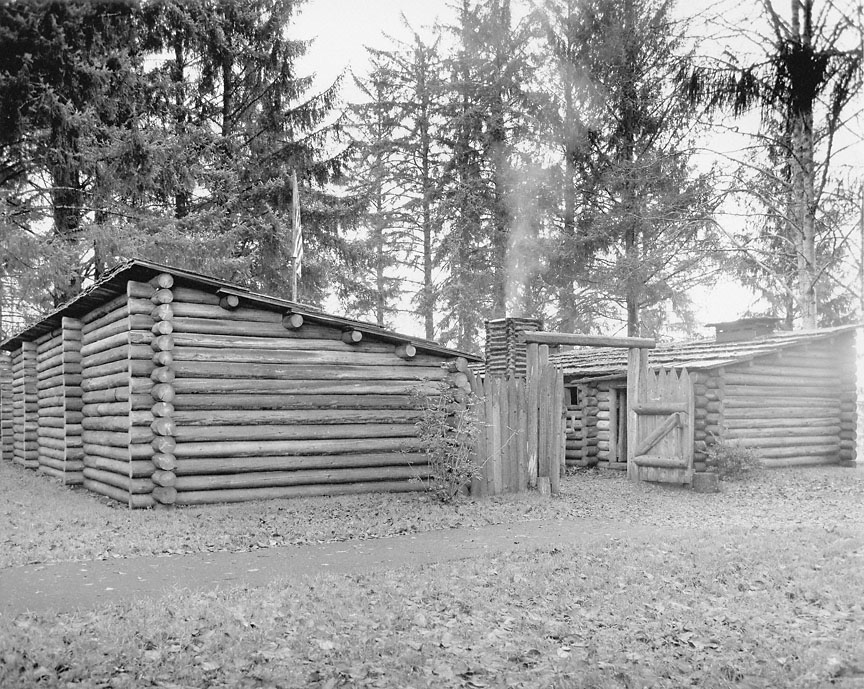

When the Corps of Discovery reached the place they called Station Camp, in the estuary of the Columbia River, Sacagawea was one of the expedition members who participated in the decision about where the winter quarters, later named Fort Clatsop, would be located. Her opinion, as quoted by Clark, was that she desired to spend the winter sensibly near where the most “Potas” roots grew.

We have very few references as to the character of Sacagawea. We know that she once had the temerity to jump into the Missouri River to save some important articles that were floating away after the pirogue carrying them nearly capsized. We know that Charbonneau once struck her and that Clark reprimanded him for it. We also know that Clark was fond of her and her child, Jean Baptiste, even offering at the end of the expedition to educate and eventually adopt him.

Sacagawea’s assistance and connections to the Lemhi Shoshone, while not crucial, were certainly important, and it was a stroke of genuine good fortune for the captains that her brother was the chief of the tribe from which they needed to secure horses so they could cross the Bitterroot Mountains. From the journals, we know that she insisted on seeing the Pacific Ocean and the whale beached there. For a Christmas present in 1806, she presented Captain Clark with a dozen white weasel tails as an acknowledgement of his leadership status. We also know that one of her few personal possessions, a blue beaded belt, was appropriated by the captains to trade for a sea otter robe owned by the Clatsop Indians because Lewis desired the robe for himself.

The spelling and meaning of her name have been a source of endless discussion. Her birth tribe insists that her name is spelled Sacajawea, that it means “she who carries a burden,” and that they are the ones who named her. The other spelling, Sacagawea, comes from the Hidatsa, her adopted tribe, and means “Bird Woman,” the meaning Lewis and Clark mention in the journals. It is important to remember that both tribes had no written language at the time. Because Lewis and Clark always rendered her name phonetically with a hard “g” in the journals, however, scholars accept the Hidatsa meaning and spelling as the standard. Lewis and Clark spelled her name some fifteen ways, and Clark gave her a nickname, Janey.

Because so little is known about Sacagawea’s life beyond the time of the expedition and her presence in St. Louis in 1811, many claimants to her ancestry have emerged. While her cultural heritage is advanced as a member of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, and Comanche tribes, her lineage through the Lemhi Shoshone is the most accepted explanation of her cultural ties. The stories of her death and burial in Wind River, Wyoming, are most assuredly legend. She died of putrid fever at Fort Manuel, South Dakota, in the winter of 1812. In his list of Corps members compiled in 1825-1828, Clark lists her as “dead.” The fate of her daughter Lizette is unknown, and her son Jean Baptiste became a well-traveled interpreter and guide in his own right.

Historian Donald Jackson once said that every generation rediscovers the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and perhaps no member’s rediscovery has been more profound than Sacagawea’s. Her life story has been appropriated by corporations, social movements, state and tribal governments, and, through the United States mint, the federal government. Her image has been used to sell—and, thanks to her coin, purchase—products, including candy bars, dolls, perfume, and coffee. She has a constellation named in her honor, along with countless schools, parks, a plane, a U.S. Navy ship, and more statues than any other American woman.

Through no influence of her own, Sacagawea became a symbol for western women in their struggle for suffrage. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women seeking the right to vote exaggerated her role on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The movement credited her with being a guide, which would have been impossible given that the route of her captors to the Knife River villages was overland, not along the Missouri River. “It was in Oregon,” wrote historian Ronald Taber, “that the Sacagawea myth found life and flourished.” Thanks to the imagination of Oregonian Eva Emory Dye and her book The Conquest; The True Story of Lewis and Clark (1902) and a later account penned by a Wyoming woman, Grace Raymond Hebard, Sacagawea became a symbol for the Oregon suffrage movement. Both accounts credit Sacagawea with much more influence on the expedition than she ever exerted in reality.

Four contemporaries wrote flattering characterizations of Sacagawea. The official factor at Fort Manuel, John Luttig, wrote that “she was a good and the best woman of the Fort. Aged about 25 years, she left a fine infant girl.” Henry Brackenridge, who traveled with the Charbonneaus from St. Louis to the Knife River villages in 1811, deemed her a “good creature of mild and gentle disposition.” On August 20, 1806, William Clark wrote to her husband that “your woman who accompanied you that long, dangerous and fatiguing rout [sic] deserved a greater reward.” For her service on the expedition, Sacagawea received no pay.

And finally this from Meriwether Lewis, on May 14, 1805, following the swamping of one of the expedition’s boats: “the Indian woman to whom I ascribe equal fortitude and resolution, with any person on board at the time of the accedent [sic], caught and preserved most of the light articles which were washed overboard.” A few days later, in honor of her courage, the Captains named Bird Woman’s Creek in Montana after her.

-

![Dollar coin]()

Dollar coin.

Dollar coin Courtesy United States Mint

-

![Sacagawea, by Hart Schultz, 1918]()

Sacagawea, by Hart Schultz, 1918.

Sacagawea, by Hart Schultz, 1918 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi80340

-

![Statue in the U.S Capitol building, presented by North Dakota]()

Statue in the U.S Capitol building.

Statue in the U.S Capitol building, presented by North Dakota Courtesy U.S. Architect of the Capitol

-

![Fort Clatsop (replica)]()

Fort Clatsop (replica).

Fort Clatsop (replica) Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi100550

-

![Beaverhead Rock, Montana]()

Beaverhead Rock, Montana.

Beaverhead Rock, Montana Courtesy U.S. National Park Service

Related Entries

-

![Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)]()

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau is remembered primarily as the son of Sacagaw…

-

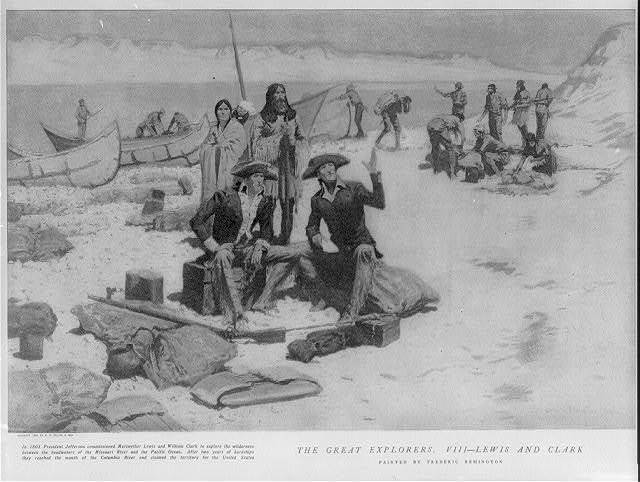

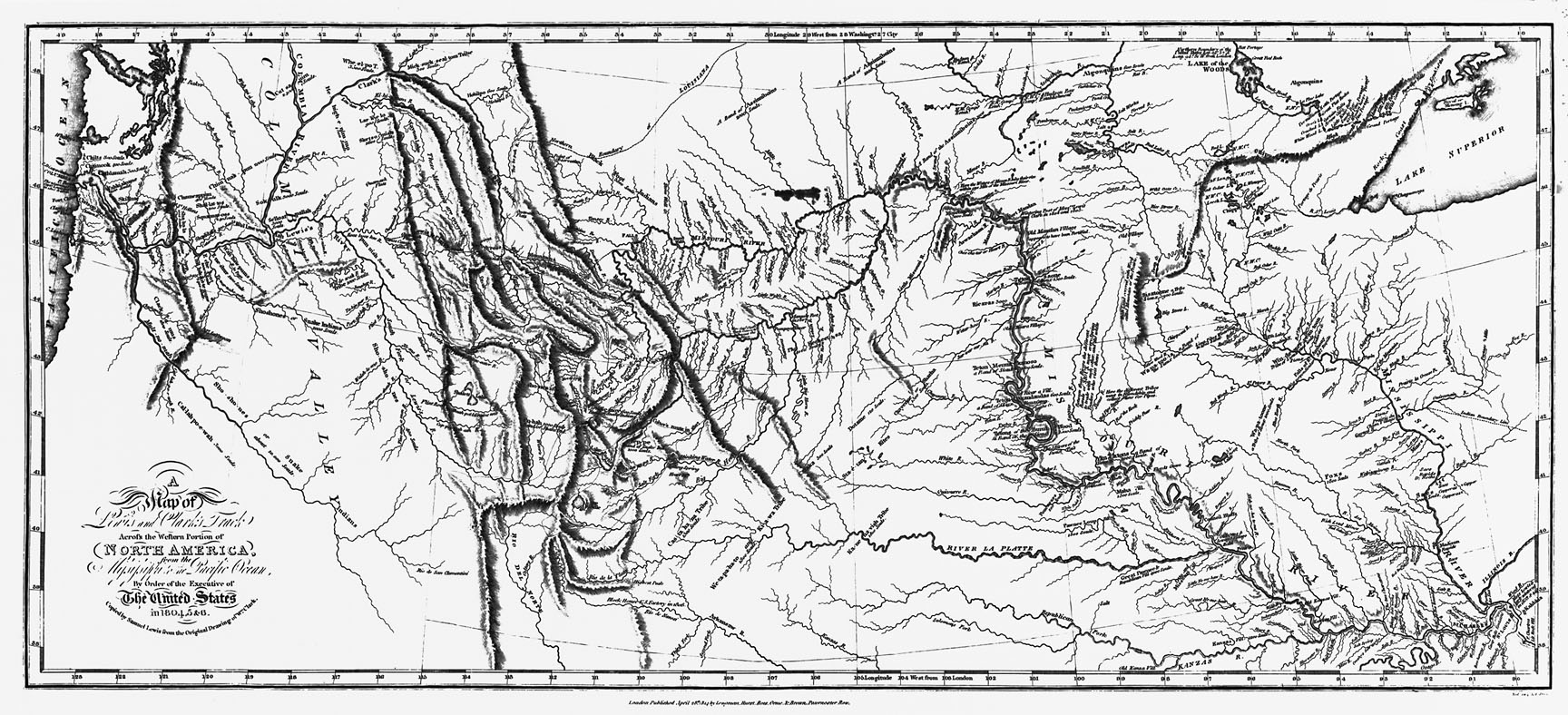

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)]()

Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)

Reflecting on Meriwether Lewis after his death, Thomas Jefferson bemoan…

-

![William Clark (1770-1838)]()

William Clark (1770-1838)

William Clark is indelibly connected to Oregon in many ways, some obvio…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Breckenridge, H.M. Views of Louisiana: Together with a Journal of a Voyage Up the Missouri River in 1811. Pittsburgh, Penn,: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1814.

Ronda, James P.. Lewis and Clark among the Indians. Lincoln: U. of Nebraska, 2002.

Taber, Ronald. “Sacagawea and the Suffragettes: An Interpretation of a Myth.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly (January 1967): 7-13

Tubbs, Stephenie Ambrose. Why Sacagawea Deserves the Day Off and Other Lessons From the Lewis and Clark Trail. Lincoln: U. of Nebraska Press, 2008.