Eleven miles north of Florence on U.S. Highway 101 are the remains of an ice-age beach of seafloor basalt, where waves hit fracture zones in the hard basalt to carve what is now Sea Lion Caves, the largest sea cave in the United States and one of the largest in the world. The main attraction is the sea lions, which sixteenth-century Spanish sailors referred to as lobos marinos, or sea wolves, perhaps because of their doglike yelps.

In 1880, Captain William Cox was the first non-Native to discover the cave, which consists of a 325-foot headland on two acres of stone “floors” and tumbled ledges upon which the present gift shop and entrance to the cave stands. In 1926, R.E. Clanton purchased the property from the Cox estate, and he was joined in his business enterprise by J.G. Houghton and J.E. Jacobson. In 1929, the original partners dropped a rope ladder to a primitive footbridge, leading to the north entrance to the cave. Sea Lion Caves opened formally to the public in 1932.

Work on the cliff trail was done by hand. The 125-foot wooden staircase to the cave’s north entrance had to be boxed in and a concrete foundation poured. The work could only be done in April and May, when the sea lions breed outside the grotto and raise their young on the rocky ledges just outside the cave. The Oregon Coast Highway was not yet completed, but the owners had permission to build a parking area east of the new highway and a gift shop/entrance on the west side. The present building is a replacement of the original, which was destroyed by fire.

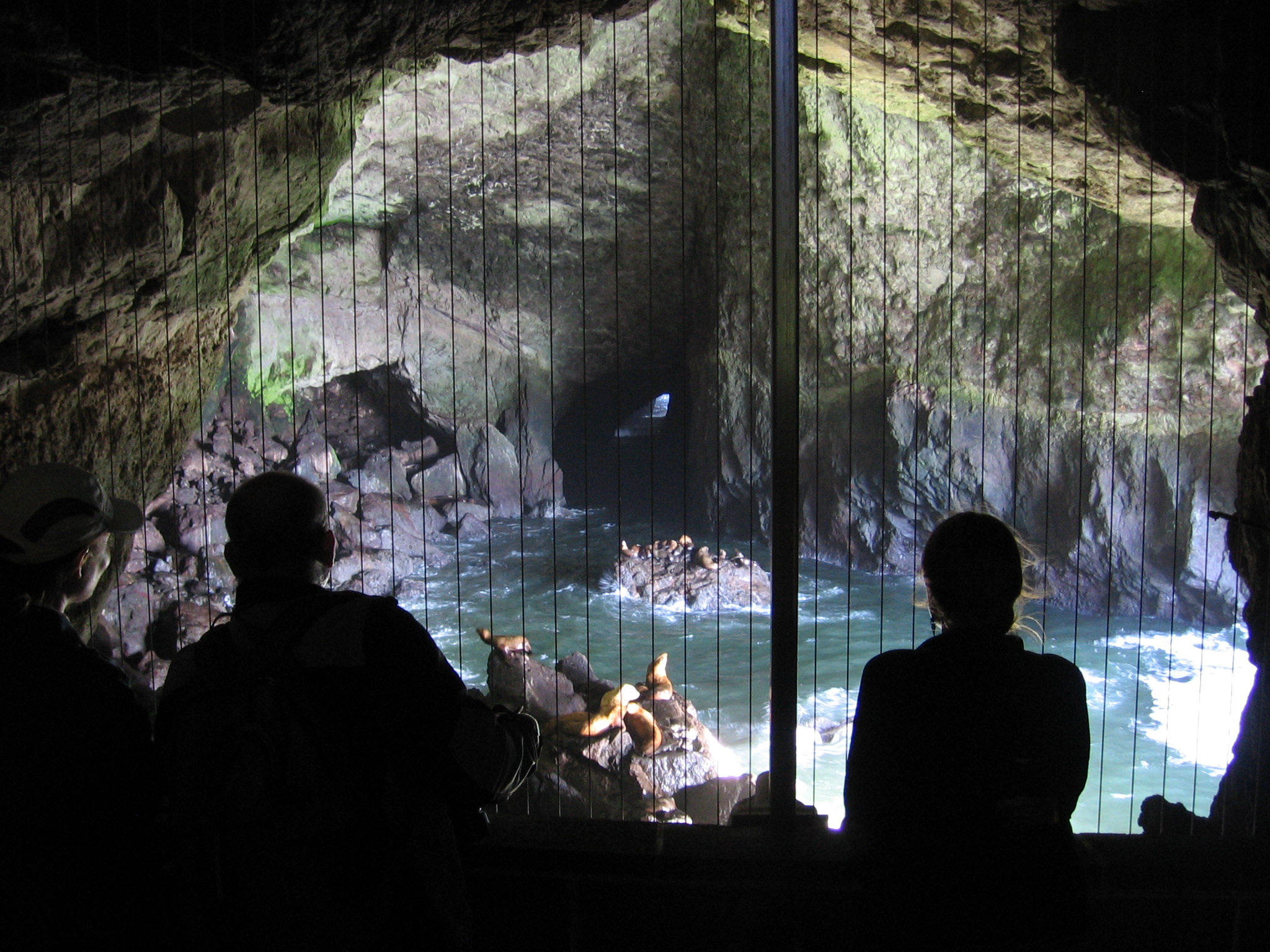

The elevator, which descends 208 feet to an observation post about 50 feet above the 1,500-foot-long cavern, cost $180,000 to construct due to salt and moisture problems. Begun in 1958, it was not opened for public use until 1961. The large natural amphitheater is behind glass to protect both tourists and sea lions.

Sea Lion Caves is the size of a football field, with a 125-foot natural rock dome. It is the only mainland rookery of Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in the contiguous United States and is home to about 200 cows, yearlings, and immature bulls. The males sometimes weigh over a ton and can be seen posturing to scare off rivals for their harems of up to 24 cows.

Until the late 1950s, the State of Oregon paid a bounty on sea lions. One hunter collected the annual limit of $10,000 for several years running. Now they are protected as endangered species, but many fishermen are unhappy with this designation, claiming that the sea lions present an unfair competition in the salmon business.

In 1977, there was a movement to take over the property by the State of Oregon, but it was unsuccessful. Governor Robert Straub praised the owners for being able to protect the natural resource and still show a profit. By 1981, the cave was realizing a gross income of over one million dollars. The cave attracts over 200,000 persons annually, who can ride the elevator or take a steep downhill walk to view the coastal cliffs and the several kinds of gulls and cormorants that nest there. The attraction is open seven days a week, except Christmas, and employs about forty-five people. Clanton withdrew from the partnership in 1934 and Roy A. Saubert stepped in. Members of the Saubert and Jacobson families have owned and operated the property ever since (the Houghtons withdrew in 2006).

In 1982, a life-sized bronze statue of a sea lion family was erected at a cost of $75,000 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of operation.

-

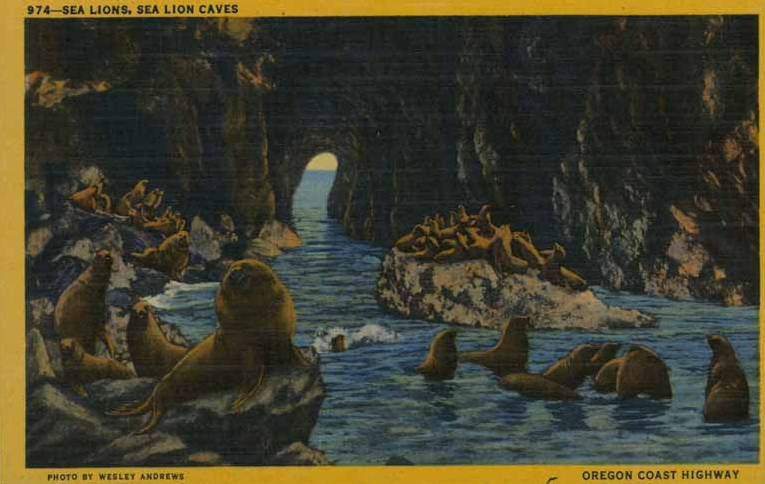

![Inside Sea Lion Caves, about 1937.]()

Sea Lion Caves, 1937.

Inside Sea Lion Caves, about 1937. Univ. of Wash. Libraries. Special Collec. Div., Postcard Collec., AWC2548

-

Sea Lion Caves, interior, 1, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves elevator, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, interior, 2, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves stairs, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, interior, 3, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves interpretive area, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, skeleton, Jul 2011.

Remains of sea lion bull, Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, interior, 4, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves interpretive area, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, interior, 5, Jul 2011.

Sea lion skeleton at Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, sea lions, 2, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, sea lions, 3, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, sea lions, 1, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, sea lions, 4, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, sea lions, 5, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, rookery, Jul 2011.

View of sea lion rookery, Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

Sea Lion Caves, statue, Jul 2011.

Sea Lion Caves, July 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Alt, David D., and Donald W. Hyndman. Roadside Geology of Oregon. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing Co., 1990.

Dicken, Samuel N., and Emily F. Dicken. The Making of Oregon, A Study in Historical Geography. Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1979.