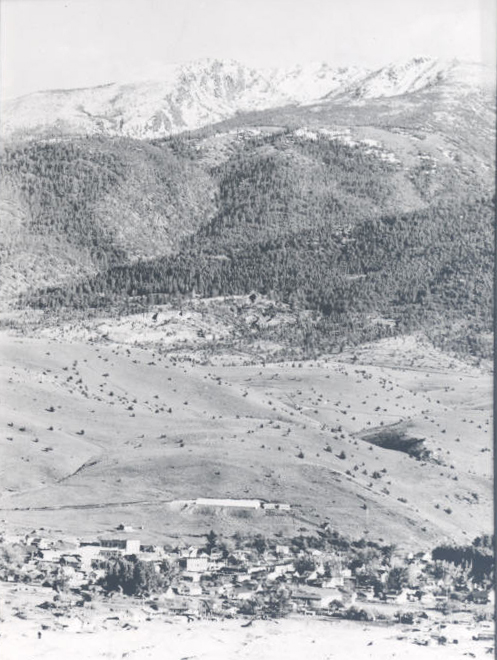

Seneca is a small town in Bear Valley near the Blue Mountains and the Malheur National Forest in Grant County. Located on Highway 395 between John Day and Burns, the town is south of the confluence of the Silvies River and Bear Creek. Nestled in a mountain valley at about 4,600 feet, Seneca offers views of the Strawberry Mountains, the highest peaks in the Blue Mountains. Logging and ranching have been important industries, and a wigwam burner from the Seneca Lumber Company still stands as a reminder of the town’s history. Seneca residents also have the honor of enduring some of the coldest temperatures in Oregon, including a record-breaking minus 54ºF on February 10, 1933.

In the centuries before whites arrived in the area, the homelands of Northern Paiute and Cayuse included a large area of present-day eastern Oregon, and they used the Bear Valley for harvesting rabbits, birds, and trout and for gathering roots, seeds, and plants. In 1878, the U.S. Army waged war on the Northern Paiutes during the so-called Bannock War—a conflict that also embroiled the Shoshone, and other bands. The army overwhelmed the Paiutes and removed them to reservations. Their descendants are now members of the Burns Paiute Tribes and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs.

Homesteaders and trappers settled in the area during the late 1800s, and a post office was established on September 17, 1895. The first postmaster, Minnie Southworth, named the town for Seneca Smith, her brother-in-law and a prominent judge in Portland. By 1890, 188 people lived in the Bear Valley Precinct. Within a few years the town had a store and a few ranching homesteads, but it was primarily a stage stop for miners and suppliers on their way to Canyon City and the gold mines. By 1920, the population of Seneca and the surrounding area had dwindled to 110 people.

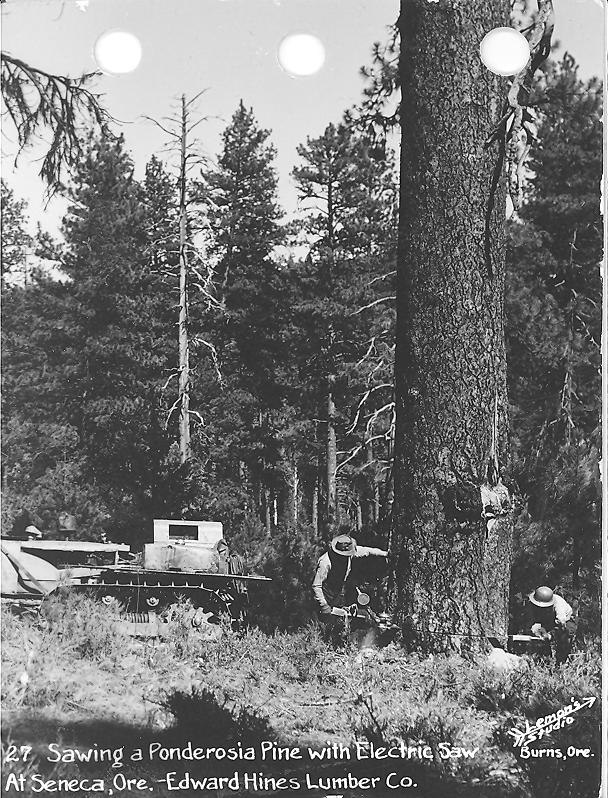

In the early 1920s, the U.S. Forest Service laid out and advertised the Bear Valley Unit within the Malheur National Forest, the largest federal timber sale offered to that time in the Pacific Northwest. The sale, which covered 67,400 acres and held the promise of 890 million board feet of timber—mainly large ponderosa pine—was put out for bid in 1923. The contract was awarded to an out-of-state timberman named Fred Herrick, who outbid the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Co. Herrick had difficulty fulfilling the mill and railroad construction requirements, which prompted Edward (or Ephraim) Barnes—a local timberman who favored Brooks-Scanlon and wanted access to private timber stands—to call for a federal investigation into fraud. Herrick was exonerated, but he ran out of money and sold his interest to the Edward Hines Lumber Company in June 1928. Barnes, who encouraged the sale, signed on as an advisor.

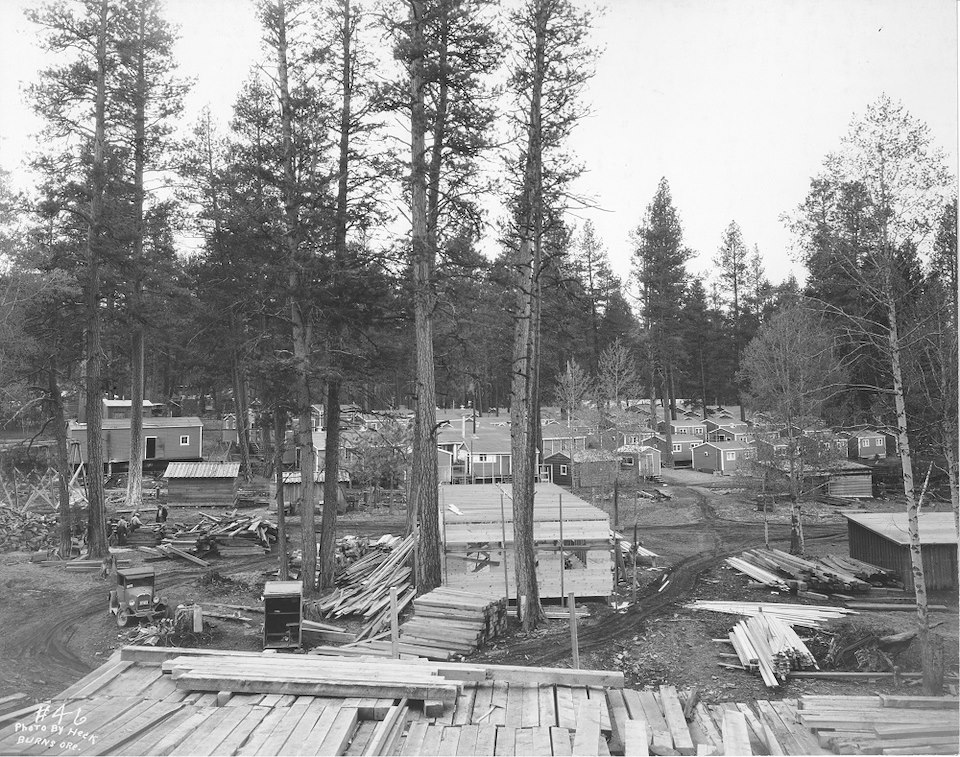

That same year, Barnes bought 800 acres of land from the Lincoln Ranch and created the Seneca Company in order to relocate and develop the town of Seneca in support of the Hines logging operation. The Seneca Company raised funds for a railroad yard, repair shops, a store, and homes that residents could purchase. A bar, movie theater, and a swimming pool, heated by steam from the plant, followed. In order to move logs from Seneca to the company’s mill in the town of Hines, just south of Burns, Hines Lumber completed the fifty-two-mile-long Oregon & Northwestern Railroad (O&NW) in 1929.

By 1930, 635 people lived in Seneca, including workers at Camp 1, a lumber camp the company operated nearby. Most residents worked in the woods cutting timber or in the Hines Lumber Company planing mill and railroad workshops. The railroad relied on Seneca facilities to maintain tracks and equipment. Although Hines did not own any of the land or the buildings, the town operated much like a company town—nearly all of the residents worked for and depended on the lumber company.

Thousands of sheep and cattle were summered in the high country near Seneca, and the railroad was the primary way livestock was transported from Bear Valley to Burns and beyond. The O&NW was a standard gauge railway, and livestock could be shipped on the Ontario-Burns branch of the Oregon–Washington Railroad & Navigation Company (which became part of the Union Pacific Railroad) without having to change tracks. Until about 1940, the Seneca station shipped about four hundred cars of livestock a year, mostly sheep. By 1959, when roads and trucks had become more common, the railway was carrying only seven cars of cattle and no sheep.

Seneca had a population of 275 people when it was incorporated in 1970. Logging continued in the Bear Valley Unit through 1968, but it began to decline in the area during the early 1970s. The Hines mills and the railroad ceased operations in 1984. Nevertheless, harvesting timber and cattle ranching are still the main industries in Seneca. The town also has a post-and-pole mill, operated by Iron Triangle, and some residents work in nearby John Day and Prairie City. In 2020, about a third of workers were employed in educational services, about 20 percent in agriculture and forestry, and another 20 percent in the service industry. The Bear Valley Meadows Golf Course opened in 1996.

The Seneca School was established in 1932, primarily to serve the children of Hines Lumber Company employees. A computer lab was added to the school in 1997, and it was one of the first in Oregon to have on-line capability. In 1967, the Seneca Rope Jumpers, a group started in 1946 by Esma Reynolds, performed in Washington, D.C., at the invitation of Oregon’s congressional delegation. Since the early 2000s, the students and local artists-in-residence have captured Seneca’s history on murals through “The Murals and the Timeline: Our History Expressed in Art,” a project of the Seneca School History Project. The population of Seneca was 164 in 2023.

-

![Ben Maxwell, photographer.]()

Street view of Seneca in Grant County, Oregon, 1962.

Ben Maxwell, photographer. Courtesy Salem Public Library Historic Photograph Collections, Salem Public Library, Salem, Oregon, 6831 -

![]()

Wigwam burner in Seneca, Grant County, 2010.

Courtesy Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives, Northwest Digital Archives -

![]()

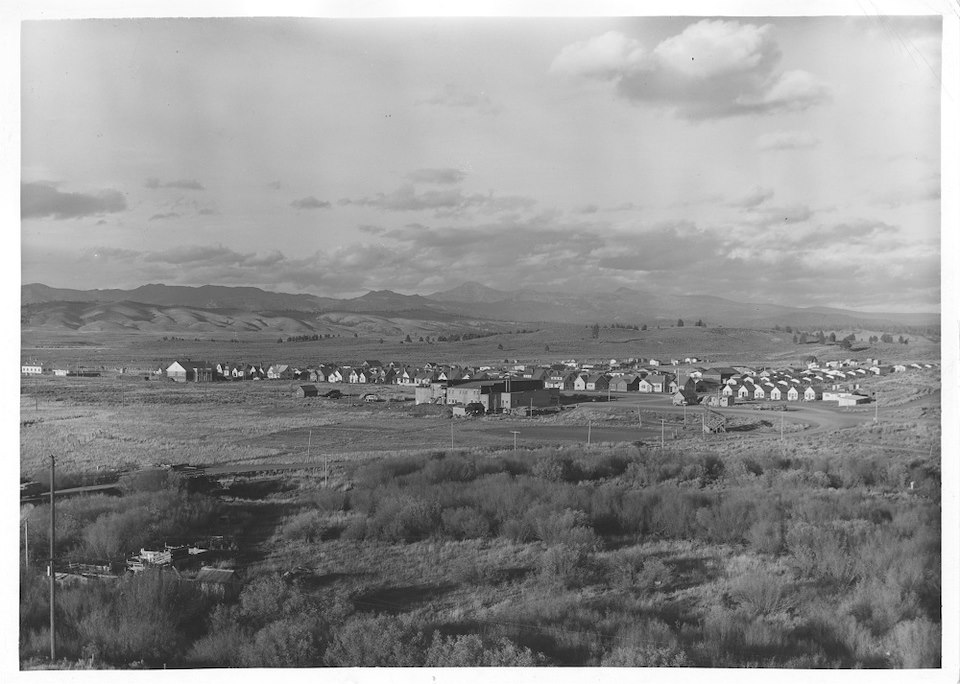

Seneca town site, view to the northeast, c.1930.

Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Edward Hines Lumber Co. Collection, 2017.021.101 -

![Rufus W. Heck, photographer.]()

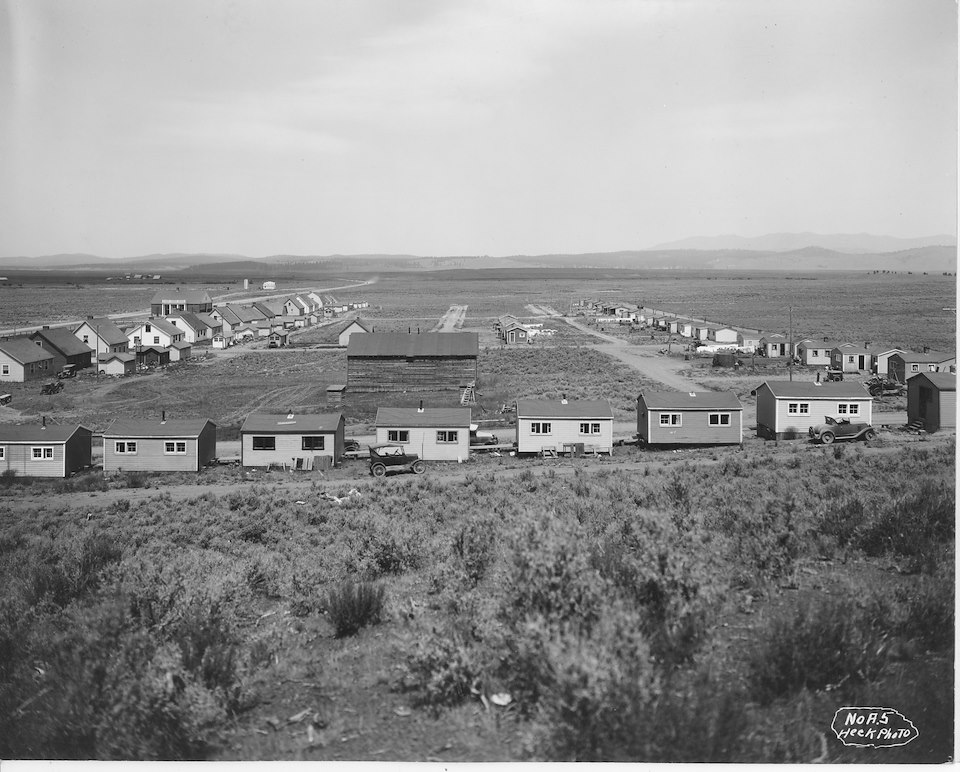

Panoramic view of Seneca, left half of two, 1931.

Rufus W. Heck, photographer. Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Presley Collection, 2017.016.39 -

![]()

Panoramic view of Seneca, right half of two, 1931.

Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Presley Collection, 2017.016.40 -

![]()

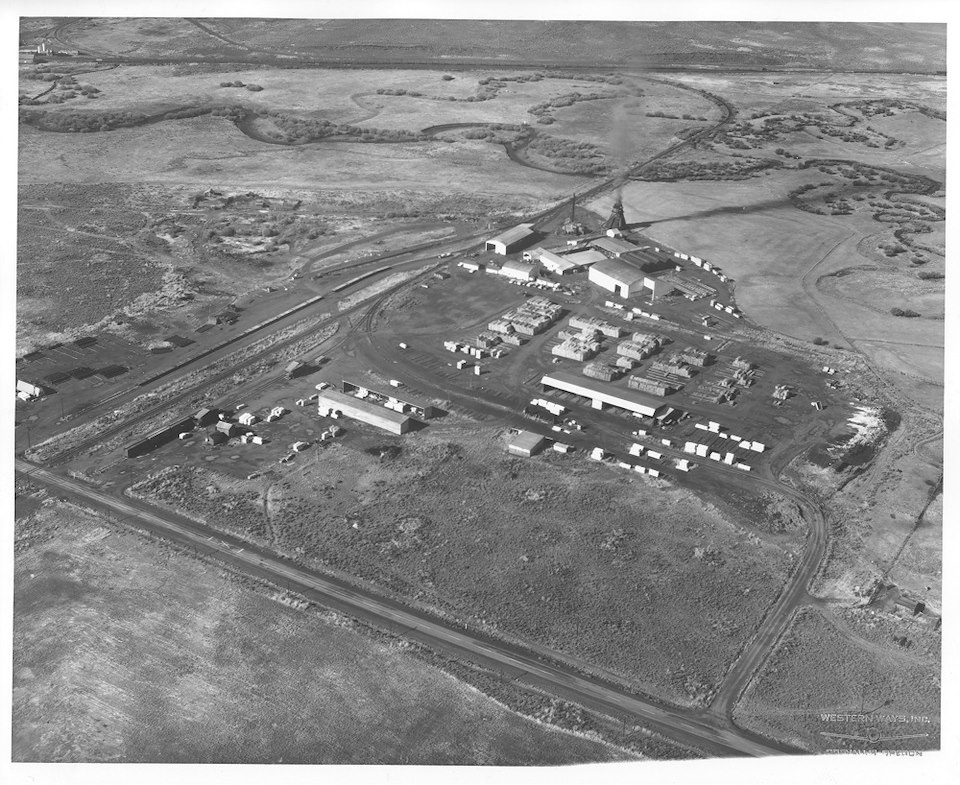

Aerial view of Seneca Planer Mill, 1969.

Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Edward Hines Lumber Co. Collection, 2017.021.099 -

![Ben Maxwell, photographer.]()

Street view of Seneca in Grant County, Oregon, 1962.

Ben Maxwell, photographer. Courtesy Salem Public Library Historic Photograph Collections, Salem Public Library, Salem, Oregon, 6830 -

![]()

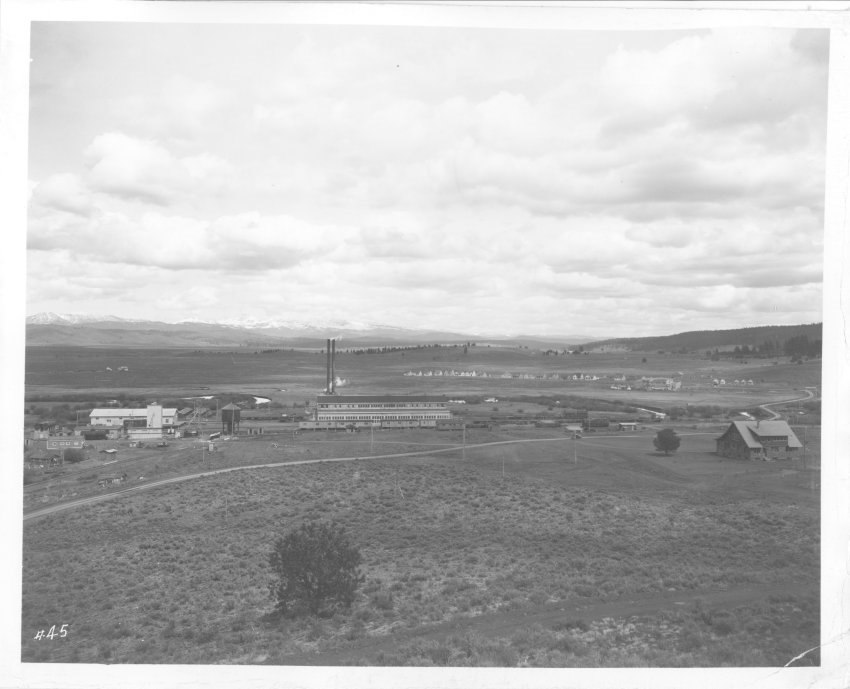

Locomotive shop and mill manager's house, c.1930.

Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Edward Hines Lumber Co. Collection, 2017.021.103 -

![Lodging for single mill and railroad workers.]()

-

![Constructed to house single mill and railroad workers.]()

-

![Robert Lemons, photographer.]()

Sawing Ponderosa Pine near Seneca, Oregon.

Robert Lemons, photographer. Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, 2007.578.1 -

![]()

Logging Camp One, near Seneca, c.1930.

Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Edward Hines Lumber Co. Collection, 2017.021.104 -

-

![]()

-

![]()

Children in Seneca Swimming Pool.

Courtesy Claire McGill Luce Western History Room, Harney County Historical Museum, Edward Hines Lumber Co. Collection, 2017.021.094 -

![Ben Maxwell, photographer.]()

Seneca, Oregon railway scene, 1962.

Ben Maxwell, photographer. Courtesy Salem Public Library Historic Photograph Collections, Salem Public Library, Salem, Oregon, 6832 -

![]()

Seneca stores with bar below 7Up sign, 1979.

Courtesy Northwest Folklife Digital Collection, University of Oregon. "Seneca stores with bar below 7Up sign" Oregon Digital -

![]()

A field along Highway 395 near Seneca, 2012.

Courtesy Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives, Northwest Digital Heritage -

![]()

Seneca School, Grant County, 2007.

Courtesy Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives, Northwest Digital Archives

Related Entries

-

![Blue Mountains]()

Blue Mountains

The Blue Mountains, perhaps the most geologically diverse part of Orego…

-

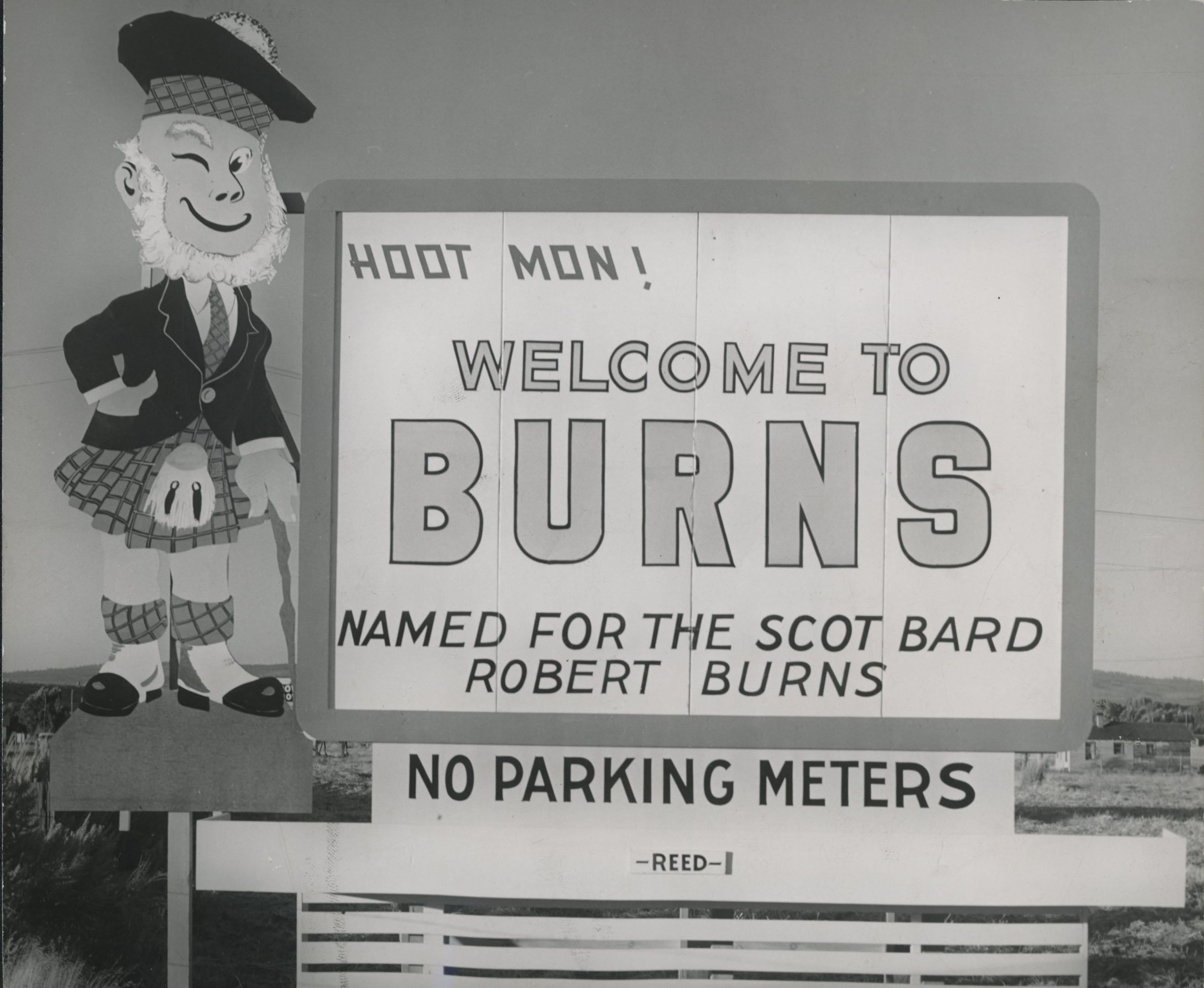

![Burns]()

Burns

Located in Oregon’s High Desert, Burns is the county seat of Harney Cou…

-

![Company Towns]()

Company Towns

While there have been scores of industrial settlements and communities …

-

Hines and the Edward Hines Lumber Company

In the mid-1920s, large sawmill owners in the United States found a new…

-

![Strawberry Mountains]()

Strawberry Mountains

The Strawberry Mountains—among the highest peaks in the Blue Mountain R…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Langston, Nancy. Forest Dreams, Forest Nightmares. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995.

Oliver, Herman. Gold and Cattle Company. Edited by E.R. Jackman. Portland, Ore.: Binfords and Mort Publishers, 1961.