The deadliest fire in Oregon history occurred on Christmas Eve in 1894 in Silver Lake, an unincorporated High Desert town about seventy-five miles south of Bend and a hundred miles north of Lakeview. Although only about 50 people lived in Silver Lake at the time, between 160 and 200 people had gathered at the J. H. Clayton community hall that night to celebrate the holiday with music, the exchange of gifts, and a dance. The hall, located on the second floor of the F. M. Chrisman general store, was decorated with pine garlands and a large Christmas tree decorated with cotton, paper chains, strings of popcorn, and presents. In the glow of oil-burning lamps, everyone was crowded together on long wooden benches.

At about eight o’clock that evening, eighteen-year-old George Payne, from the nearby town of Summer Lake, stood on a bench to look across the room. As he stood up, his head hit one of the oil lamps, spilling burning oil on Payne and the wood floor. In seconds, a fire was raging, and the crowd panicked and rushed for the only door that led to the stairs. Those who made it to the door were crushed against it by the force of those behind them. As the fire spread, people outside tried to force their way into the building to help, but the door, which opened inward, was stuck closed. Within minutes, the stairway had collapsed and the building was completely on fire. The only escape was to jump out of a window.

In less than an hour, the building was a smoking ruins. Forty people died that day, and another three would die later from injuries suffered in the fire. All of the pain remedies and treatments in the general store were lost in the fire, and the town’s only doctor, W. M. Thompson, was making a house call fifty miles away. One man rode to get Dr. Thompson while Ed O’Farrell, a twenty-two-year-old cowboy, rushed to alert Bernard Daly, a doctor who lived in Lakeview. O’Farrell rode for nineteen hours in minus-twenty-degree weather, stopping only to change horses and arrange for fresh horses for his return. He reached Lakeview at about four o’clock in the afternoon on Christmas Day. Dr. Daly left soon after, traveling as far as Paisley by buckboard wagon and then on horseback to Silver Lake, sometimes through snow that was reportedly as high as the horse’s belly.

Dr. Daly reached Silver Lake at six o’clock the next morning and immediately began working with Dr. Thompson to treat the injured, who were being cared for in private homes and on pallets in the local saloon. There were later reports that so many linens were used for bandages that all of the homes in the area had few left for the rest of the winter, until mule trains arrived in the spring with supplies. All but three of the injured survived.

It took four days by mail stage and telegraph for news of the tragedy to reach Portland. The story first appeared in the December 29 Morning Oregonian, followed by a report in the New York Times and other newspapers. In 1905, the Illustrated History of Central Oregon, which included an extensive entry on Silver Lake and the fire, referred to the town as the “Gateway to the Oregon Desert” and concluded that there was probably no other town in America farther from a railroad than Silver Lake. In that remote part of Oregon, Silver Lake had some prominence, as it was the only established trading post between Lakeview and Prineville, a distance of about two hundred miles.

Five days after the disaster, Silver Lake residents buried those who had died in the fire in a common grave at a small cemetery to the east of town on Route 31. In 1898, the community erected a ten-foot-high granite monument with the names and ages of all who had perished as a reminder of the event. Of the forty-three who died in the fire, nineteen were women, sixteen were men (including young George Payne), and eight were children. More than a century after the Christmas Eve fire, the memories of that tragedy remain in Silver Lake.

Following the accounts of the disaster, newspapers around Oregon called for increased fire safety measures in public buildings, including more exits and fire escapes. In 1909, Representative Robert Farrell (Multnomah) introduced a bill to the state legislature requiring the doors of public buildings to open outward. In a joint session, Senator Charles Parrish (Grant, Harney, Malheur) stood to speak in support of the law, breaking down in tears as he recalled the Silver Lake Fire. The bill passed, and the law still stands.

-

![]()

Silver Lake Fire Cemetery Monument.

Courtesy Sam Stern

-

![]()

Oregonian article, January 2, 1895.

Courtesy The Oregonian

-

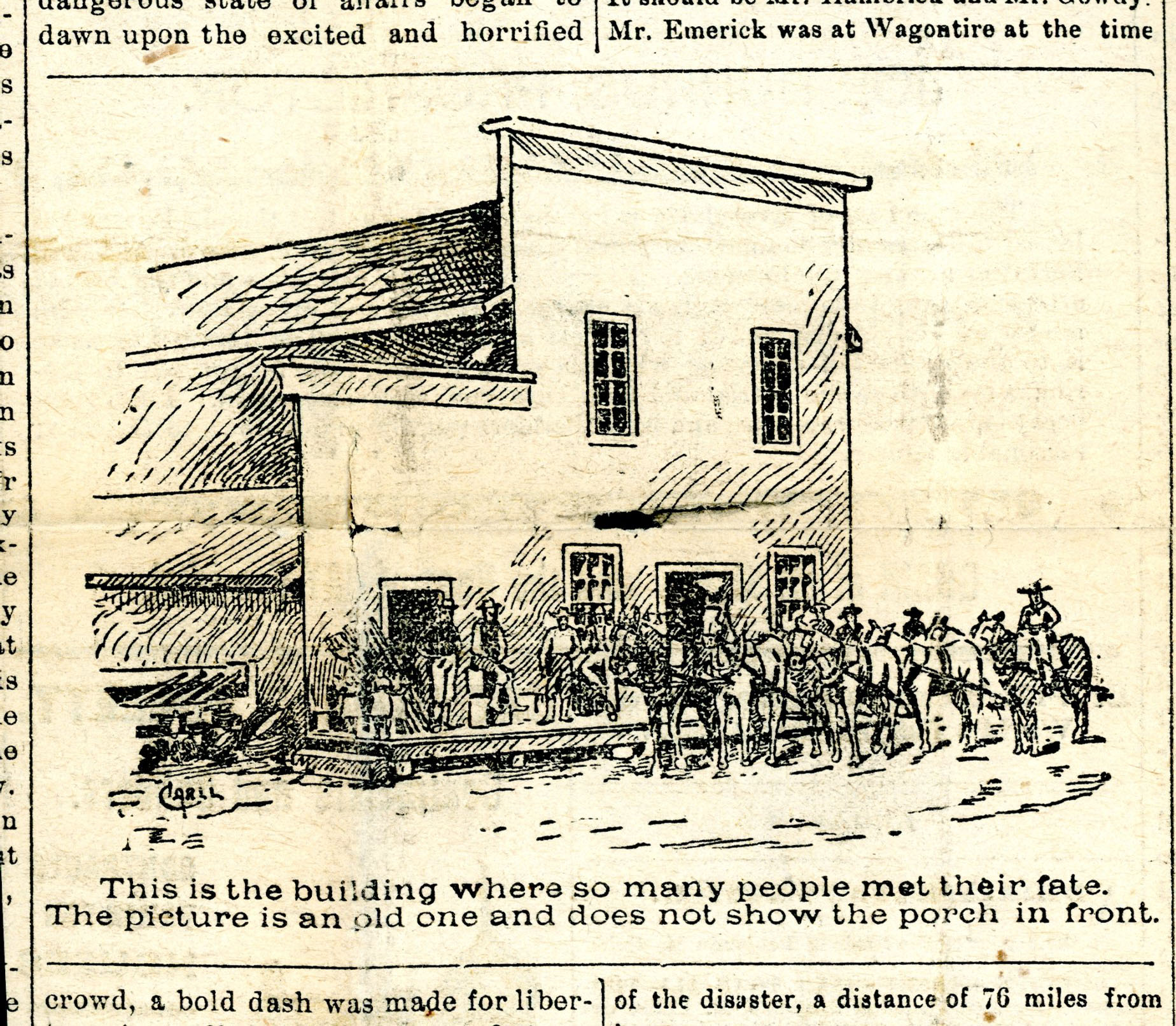

![]()

Sketch of the Chrisman General Store, Silver Lake, Lakeview Examiner, January 24, 1895.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Lakeview Examiner, Silver Lake Fire vertical file

Related Entries

-

![Bernard Daly (1858–1920)]()

Bernard Daly (1858–1920)

Bernard Daly did much to improve the lives of Oregonians, particularly …

-

![Lakeview]()

Lakeview

The City of Lakeview, in northern Goose Lake Valley at an elevation of …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bottomly, Therese. “The 1894 Christmas Eve Fire in Silver Lake Scarred Remote Community for Decades.” Portland Oregonian, August 29, 2018.

“1894 Christmas Eve Fire Spurred Safety Legislation.” The Columbian, December 25, 2013.

Shaver, F. A. Illustrated History of Central Oregon. Spokane: Western Historical Publishing Company, 1905.

Tupper, Melany. High Desert Roses: Significant Stories from Central Oregon. Christmas Valley, Ore.: Central Oregon Books, 2003.