Gus J. Solomon, the second-longest-serving federal judge in Oregon history, was the Portland-born child of newly wealthy immigrant East European Jews. He was crucially shaped by their communal traditions and immigrant neighborhood and by the pressures on his family and neighbors to assimilate and be model citizens. Solomon emerged in adulthood as a centrist New Deal liberal, Jewish activist, civil libertarian, patriot, and middle-class white male.

After spending a term at the University of Washington, Solomon flourished for two years at Reed College in Portland. "At Reed," he later remembered, "I became quite a liberal," and he drew closer to Judaism's traditions of protest and the obligation to repair the world.

In 1926, at twenty, Solomon graduated from the University of Chicago and headed to Columbia University's law school. A year there made him an advocate of judicial restraint. His practical and fact-based adjudication owed much to the Legal Realism he learned at Columbia. In 1929, he graduated from Stanford University's law school and started his career in Portland.

The Depression severely restricted Solomon's plaintiff and business law practice, as did antisemitism, and he earned scant income. As a youth, Solomon had enjoyed a tranquil, comfortable, and uneventful life—except for antisemitic experiences. Jews were routinely stigmatized, condescended to, and discriminated against, he later remembered, "in education, job opportunities and social activities." Mainly because of those humiliations and Jewish social justice traditions, he "became active as a young lawyer in the problems of the poor" and in the struggles for civil rights and liberties, "not for the Jews alone—but for everyone."

Solomon won repute in the 1930s as a shrewd, energetic, and dedicated attorney for public-power interests and those seeking civil liberties. He promoted lawyers' involvement in social movements and helped establish the Legal Aid Society, a plaintiff attorney club, and a National Lawyers Guild chapter. He represented businesses, unions, and Communists. He worked for the struggling Oregon and Washington public-power movements and goaded his local American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) into action. In 1937, at the age of thirty, he was a driving force behind the national ACLU's landmark Bill of Rights opinion, Dirk De Jonge v. State of Oregon.

In the late 1930s, Solomon helped direct the statewide Oregon Commonwealth Federation, a grassroots liberal and inter-racial political coalition. During the 1940s, he was active in Oregon's minority Democratic Party, a chapter of the liberal Americans for Democratic Action, and the campaigns of Republican Wayne Morse and President Harry S Truman.

Solomon toiled for Japanese Americans returning from forced internment in 1944-1946. By then, Solomon enjoyed a sizable reputation in New Deal and northwestern liberal circles. He also continued to be Red-baited (despite being vocally anti-Communist) and assailed as a Jew or a traitor—never more so than during his bruising 1949-1950 battle to join the U.S. District Court for Oregon, a position he won in 1950.

The forty-three-year-old outsider uneasily took his District Court seat and rapidly mastered its complicated ways while trying to put his ideas into action without violating court norms. (Businesses, he chortled, liked this liberal judge.) Over time, lawyers and judges acknowledged Solomon's caliber, immense output, and the high approval rate of his decisions by higher courts. He created a collegial court during his 1958-1971 Chief Judgeship and introduced efficiencies into the District's Court as it dealt with a multitude of federal laws, court filings, and legal practitioners. Solomon served on numerous boards and repeatedly sat on appellate courts' panels, where he had more potential influence on the law than in a district court.

Generally thought fair by lawyers, Solomon shrugged off criticism that he had an abrasive judicial temperament. While he heavily ruled for Bill of Rights freedoms and minority opportunities and rights, he tempered those sympathies when judging accused or convicted criminals, certain types of draft offenders, and alleged Communists. Even then, he tried to provide due process of law, fair sentencing, improved prisons or substitutes for young draft resisters, and proper treatment of the mentally ill.

Since 1938-1939, Solomon had been a Jewish activist. Privately and through Jewish organizations, Judge Solomon labored for minority rights, coalitions with non-Jews and African Americans, Israel, and other issues. From the 1950s into the 1970s, he played a major role in opening Portland law firms and social clubs to Jews. But many changes in the 1960s, particularly the diminishment of New Deal liberalism, made him wary, angry, or both, and colored his judicial decisions.

Solomon married Elisabeth Willer in 1939. They had three sons—Gerald, Phillip, and Richard. He served on the District Court bench until his death on February 15, 1987. To honor Solomon's contributions to the law and to Oregon, Portland's Gus J. Solomon United States Courthouse was named for him in 1989.

-

![Gus & Libby Solomon.]()

Solomon, Gus & Libby, with chopsticks.

Gus & Libby Solomon.

-

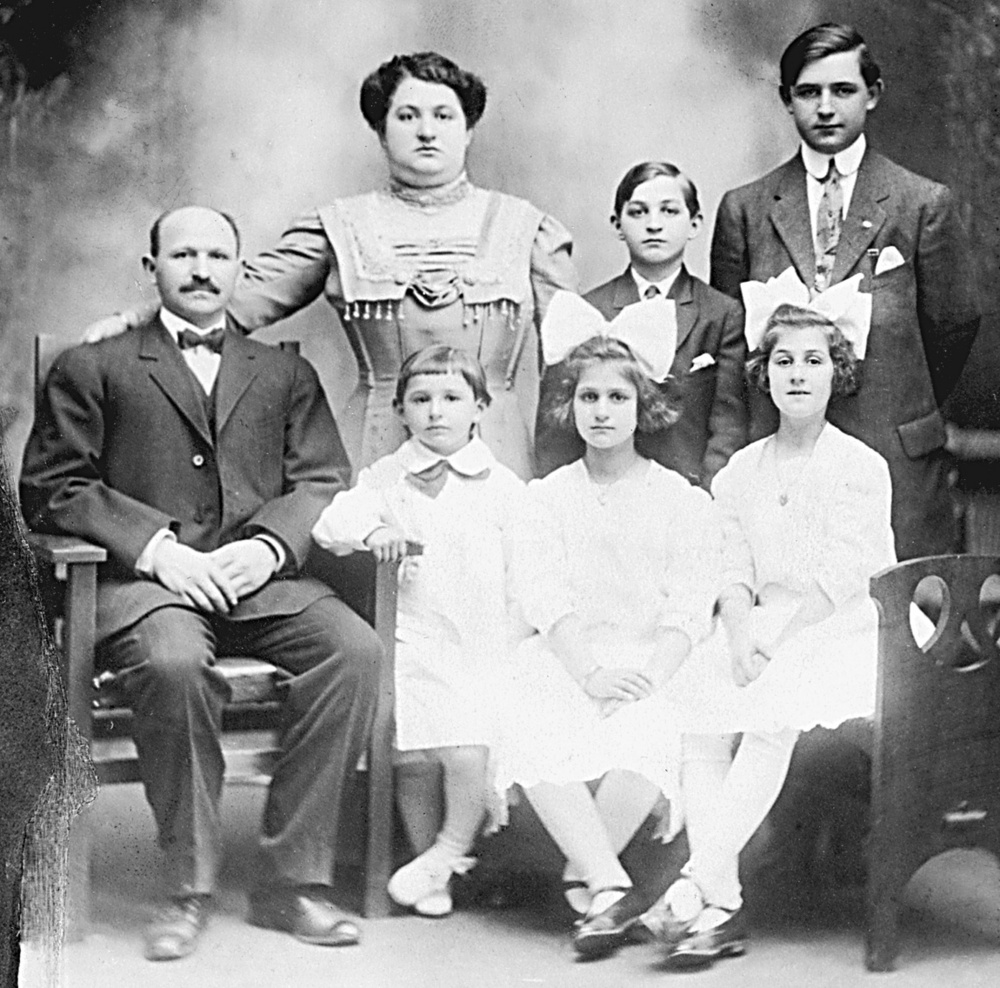

![Solomon family, with Gus as a child.]()

Solomon, Gus, as child with family.

Solomon family, with Gus as a child.

-

![]()

Gus Solomon.

Courtesy Richard Solomon

-

![Gus Solomon with group of judges.]()

Solomon, Gus, in group portrait of judges.

Gus Solomon with group of judges.

-

![Gus Solomon with Monroe and Lillie Sweetland.]()

Solomon, Gus, and Sweetlands.

Gus Solomon with Monroe and Lillie Sweetland.

Related Entries

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Jews in Oregon]()

Jews in Oregon

Jewish Pioneers: Becoming Oregonians In 1869, Bernard Goldsmith, an i…

-

![Oregon Commonwealth Federation]()

Oregon Commonwealth Federation

Following the inaugural meeting of the Oregon Commonwealth Federation (…

-

![Reed College]()

Reed College

Situated on 116 acres in southeast Portland, Reed College enrolls nearl…

-

![Wayne Morse (1900-1974)]()

Wayne Morse (1900-1974)

Wayne Morse and the Vietnam War: the name and the conflict will be fore…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Stein, Harry. Gus J. Solomon: Liberal Politics, Jews, and the Federal Courts. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2006.