The Hobsonville Indian Community was a Native settlement on Tillamook Bay, just southeast of Garibaldi on Miami Cove. Tillamook tribal villages, including Kilharhurst, fronted this shoreline well before European contact, and it is near this location that Captain Robert Gray—commanding the Lady Washington in August 1788—made first American landfall in what would become Oregon, there encountering and skirmishing with the Tillamook.

The Hobsonville Indian Community was a refugee settlement of later times. Taking shape through the nineteenth century and surviving well into the twentieth, the village was a home for families displaced by epidemics and agricultural resettlement in their homelands on the northern Oregon Coast. A few small nonreservation settlements persisted in this area into the nineteenth and very early twentieth centuries. In its final decades, Hobsonville represented the last nonreservation Native settlement on the northern Oregon Coast.

Chief Illga (also known as Tse-tse-no or Illga Adams) founded the transitional settlement in the final decades of the nineteenth century. Presiding over the Kilchis Point village through the mid-nineteenth century, the time of EuroAmerican contact and settlement on Tillamook Bay, Illga and his contemporary Chief Kilchis were the last chiefs to preside uncontested over the bay and the lands surrounding it. Displaced by mid-nineteenth century non-Indian agricultural resettlement, Illga, his Clatsop-born wife Kóshtewah (also known as Maggie Adams), their family, and other Tillamooks became refugees on their own lands, eking out a compromised existence on the margins of a burgeoning non-Native society.

By the 1870s, Illga and other Kilchis Point refugees had moved to the margins of Hobsonville, where John Hobson and his family had developed a small townsite with a lumber mill and a salmon-packing plant. Securing the Hobson family’s permission to occupy an unused portion of their land, Illga encouraged other displaced tribal members to regroup there, and it became a sanctuary and de facto reservation for tribal members lacking other options. Those who arrived were primarily Nehalem-Tillamook-speaking families from Tillamook and Nehalem Bays, but there were also Clatsops from the Columbia estuary and the Clatsop Plains.

The surnames of people who lived in the Hobsonville Indian Community suggest a diversity of northern Oregon Coast tribal families: Adams, Gervais, Esahtin, Swahaw, Kotata, Pearson, Osalokwis, Kilchis, Center, Goff, Scovell, Burns, Duncan (Dunkel), Larson, and others. Most hailed from communities of people who had been promised reservation lands in the 1851 Tansy Point Treaties, only to have those treaties not ratified by the U.S. Congress. Nineteenth-century Hobsonville became part of a small, interrelated network of nonreservation Native communities on the coast, including Seaside, Oregon’s “Indian Place” community, and the Chinook settlement at Bay Center, Washington.

In spite of the Hobsonville Indian Community’s proximity to non-Indian Hobsonville, the two communities were ethnically segregated. The town mill employed Native men, but tensions arose when mill expansion encroached on tribal burial sites associated with Kilharhurst and non-Native millworkers scuttled multiple burials; several men left their jobs and the community in response. In 1890, a year before Illga’s death, the chief arranged to purchase the village site from Frank Hobson, a rare instance of a federally unrecognized tribal community acquiring fee-simple title to their own land. Lacking the federal oversight experienced by reservation tribes, the Hobsonville Indian Community continued certain traditional practices without active suppression, perpetuating the Tillamook language and oral traditions and maintaining a hereditary chieftainship.

Hobsonville attracted the attention of anthropologists and linguists. In the 1930s, Franz Boas dispatched students, including May Mandelbaum and Melville and Elizabeth Derr Jacobs, to record information on Tillamook language and culture. Smithsonian Institution researchers later did the same. Each worked with Clara Pearson, a gifted storyteller, and to a lesser extent Illga’s daughters and granddaughters. Most anthropological writings on Tillamook tribal culture and language are derived from these exchanges. Even in the 1960s and 1970s, former Hobsonville residents living in nearby Garibaldi were consultants to researchers of Tillamook language and culture. Former residents living elsewhere in the state continued to serve as oral history informants well into the 2000s.

The Hobsonville Indian Community attracted non-Indians, including basket collectors and tourists who learned of the community locally and sought glimpses of “authentic Indians.” The community was also a focus of derision, according to former residents, and sometimes was visited by Ku Klux Klan members and others who occasionally taunted, threatened, and by some accounts attacked tribal residents.

Under these pressures and with few economic opportunities, young people continued to leave the community, particularly men. Toward the end of its existence, in the 1920s and 1930s, the Hobsonville Indian Community consisted largely of elderly women and their adult daughters and grandchildren, a situation that contributed to the unfortunate but widely used moniker “Squawtown.” By World War II, the community was largely defunct, with some portion of the residents moving to the town of Garibaldi.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, members of the community sought federal tribal status. Citing historical ties with the Siletz and Grand Ronde peoples, some Hobsonville descendants sought enrollment with those tribes when both were restored in the 1980s, but with limited success: a small number were granted enrollment, but most were not. Those without federal status redoubled their efforts, and Hobsonville descendants organized as the Tillamook Tribe of Oregon; they later joined forces with other federally unrecognized Clatsop and northern Tillamook descendants, together forming the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes, a nonprofit organization without formal tribal status. This effort was largely directed by Joseph Scovell from the mid-twentieth century until his death in 2014. Scovell was Illga’s great-grandson and heir within the system of traditional leadership, as well as being a childhood resident of the Hobsonville Indian Community.

As of summer 2017, the descendants of Hobsonville Indian Community continue to document their history and culture and to seek federal status, under new political leadership born after the dispersal of the Hobsonville community. A number of tribes and tribal organizations contest the legal existence of the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes as an independent entity on various grounds, seeking instead to incorporate their membership into existing tribal communities and governments or to block their access to federal status more generally, a phenomenon rooted in the fractious history of broken nineteenth-century treaties and transitory Indian Agency jurisdictions. The group has not yet secured federal recognition but is continuing to pursue such status through congressional action from its headquarters in Seaside. The lands formerly within the Hobsonville Indian Community have fallen out of tribal ownership, and no structures remain from the period of tribal habitation.

-

![]()

Tillamook Bay and the town of Hobsonville, 1912.

Courtesy Oregon HIst. Soc. Research Lib., 983D058

-

![]()

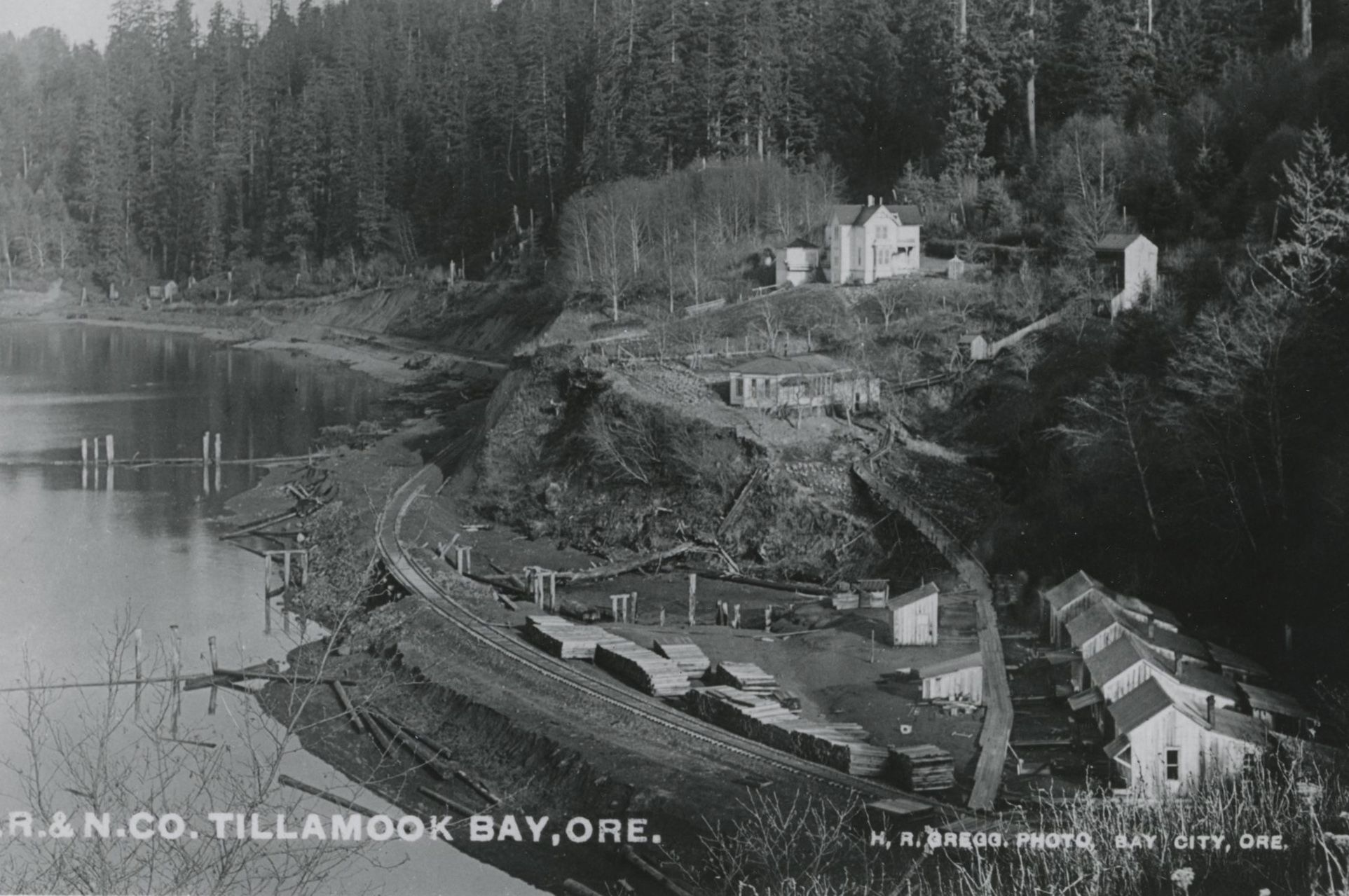

Hobsonville Mill on Tillamook Bay, Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon HIst. Soc. Research Lib., 45837

-

![]()

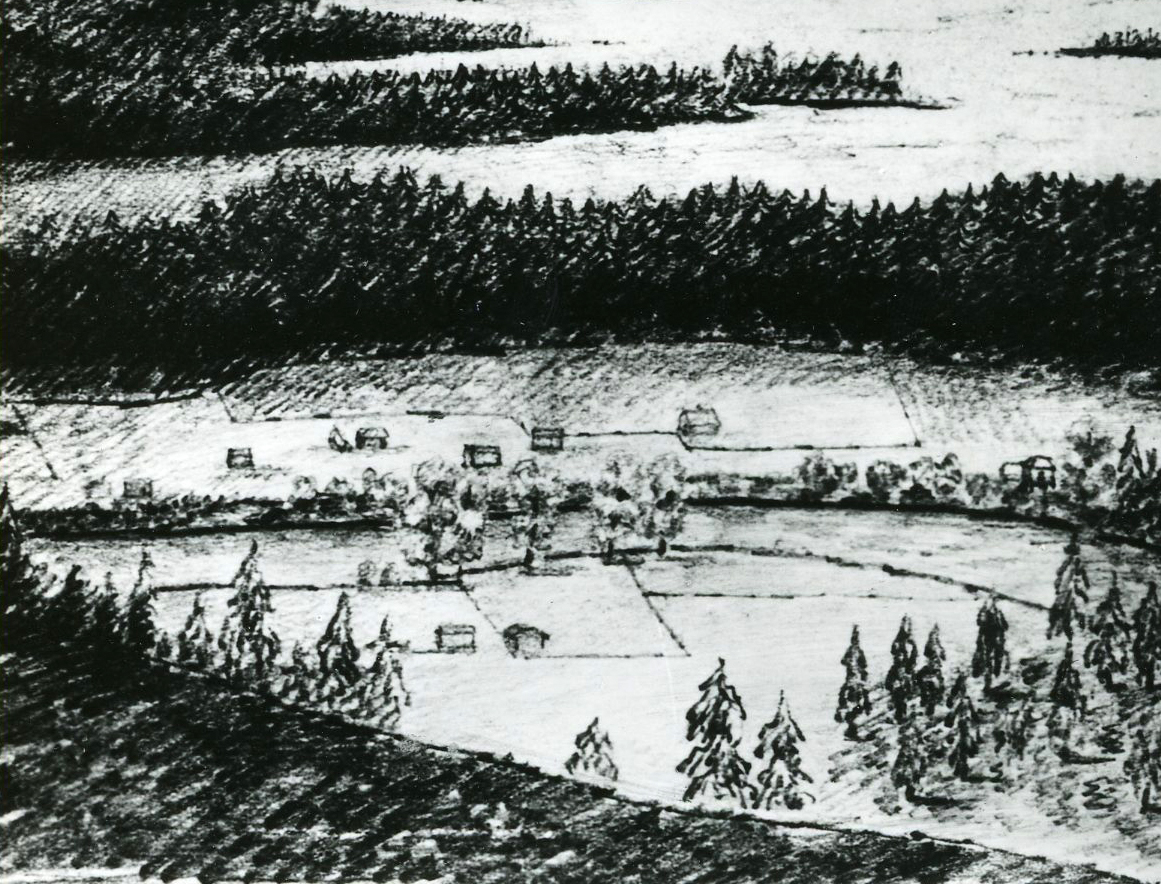

Tillamook Bay and the town of Hobsonville, Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon HIst. Soc. Research Lib., 45842

Related Entries

-

![Elizabeth Jacobs (1903-1983)]()

Elizabeth Jacobs (1903-1983)

Elizabeth D. Jacobs’s fieldwork with the Nehalem Tillamook and southwes…

-

![Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)]()

Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)

Melville Jacobs did more to document the languages, cultures, oral trad…

-

![Robert Gray (1755–1806)]()

Robert Gray (1755–1806)

On May 11, 1792, Robert Gray, the first American to circumnavigate the …

-

![Tillamook Bay]()

Tillamook Bay

Tillamook Bay, which encompasses a 597-square-mile watershed, is the la…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaty Commission]()

Willamette Valley Treaty Commission

On June 5, 1850, An Act Authorizing the Negotiation of Treaties with th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Deur, Douglas. Community, Place, and Persistence. Report to Oregon Heritage Commission, Salem OR, 2005.

_____. "The Making of Seaside’s 'Indian Place': Enduring and Contested Native Spaces on Oregon’s North Coast." Oregon Historical Quarterly (2016).

_____. Oral History Interviews with Joseph Scovell. Unpublished fieldnotes in author’s possession, n.d.

Graves, Jack. “Now” Never Lasts: Stories of Garibaldi and Garibaldians. Garibaldi, OR: Garibaldi Press, 1995.

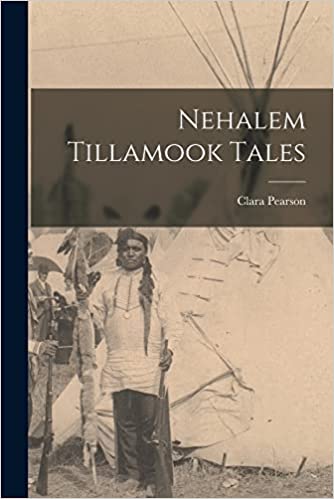

Jacobs, Elizabeth Derr. Nehalem Tillamook Tales. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1990.