One of the strains of nineteenth-century American thought was the presumption that Native peoples were fated for extinction. This ethos was communicated and recorded via itinerant portraitists and, later, photographers who rushed to the American West to capture images of what was considered a "vanishing race."

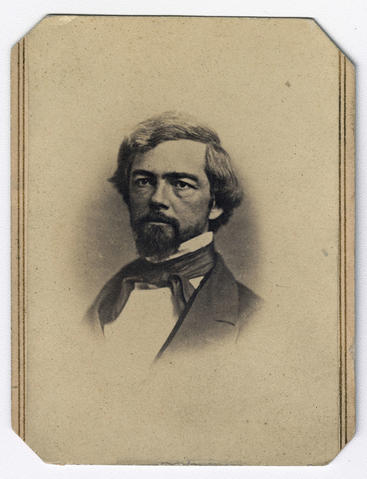

The Oregon Country became the special purview of John Mix Stanley. A lesser known figure than George Catlin and Edward Curtis, Stanley was nevertheless an accomplished artist.

Born in 1814, Stanley grew up in the Finger Lakes district of New York. He moved to Detroit where, seemingly without any formal training, he began painting the landscapes and Indians of the upper Midwest. Emulating the artist-explorer style popularized by Catlin, in 1842 Stanley undertook an expedition into "Indian Country," the Oklahoma territory recently populated by relocated tribes from the Southeast. There he refined his craft, and his work from the trip was publicly exhibited in galleries in several eastern cities.

Stanley's first venture to the Oregon Country came with his posting as a "draughtsman" for the Corps of Topographical Engineers. He was attached to Stephen Watts Kearny's battalion, which had helped conquer California in the Mexican-American War. With his passage gained to the Pacific Slope, Stanley parted company with the army and traveled north to Oregon, hoping to add to his catalog of Indian portraits and landscape scenes. Among other outcomes, his tour resulted in portraits of early Oregon pioneers Maria Pambrum Barclay and Asa Lovejoy. These, the only known Stanley portraits held in Oregon, are now in the collection of the Oregon Historical Society.

Stanley enjoyed a rather celebrated showing of his works at the Smithsonian Institution in 1852. With his reputation as a western artist in full bloom, he became acquainted with Isaac I. Stevens, commander of the Northern Pacific Railroad expedition that was to head west in the spring of 1853. In the spirit of scientific exploration, the army determined that the western surveys were to be amply illustrated.

Stanley was by far the best known of the artists attached to the expeditions and, perhaps as a consequence, the Stevens report was the most lavishly illustrated volume in the series. Together with the junior artist in the expedition, Gustavus Sohon, Stanley produced the first widely disseminated views of the northern west, from St. Paul to Puget Sound.

Stanley's return to the Atlantic seaboard in January 1854 ended both his western travels and his most creative period. In his remaining years, he operated studios in Washington, D.C., Buffalo, and Detroit, where he died in 1872. Most of his portraiture was consumed in the great Smithsonian fire of 1865, which resulted over time in the decline of his reputation as a great western artist.

-

![]()

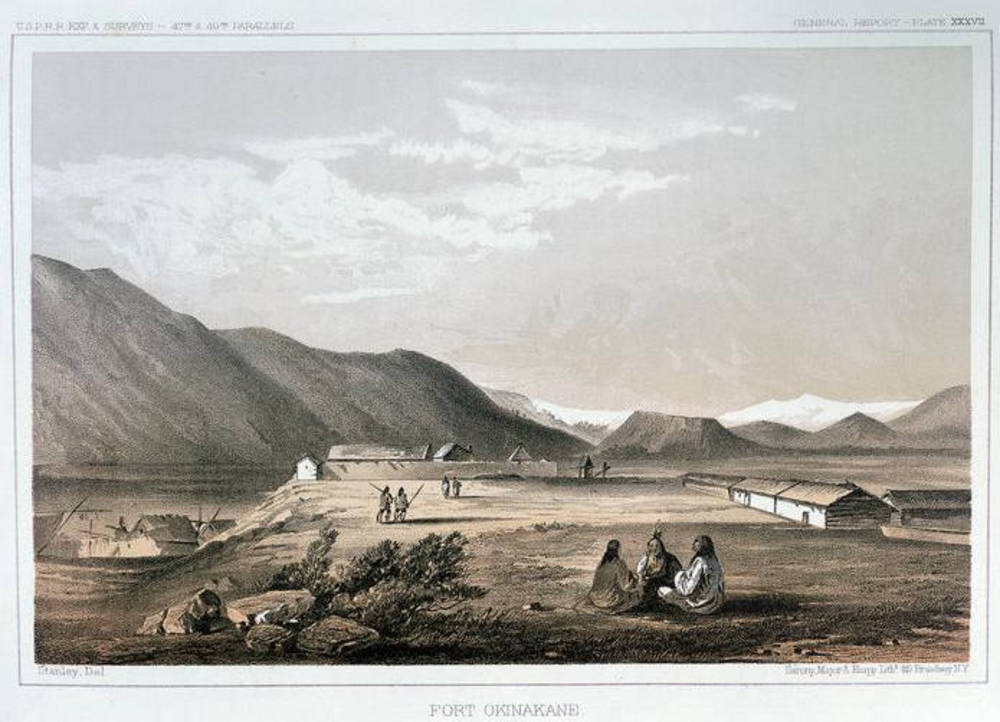

Okanagans seen in front of Fort Okanogan, engraving by John M. Stanley, 1853.

Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, NA4166 -

![]()

Klamath tule-mat covered lodges, engraving by John M. Stanley, 1855.

Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, NA4177 -

![]()

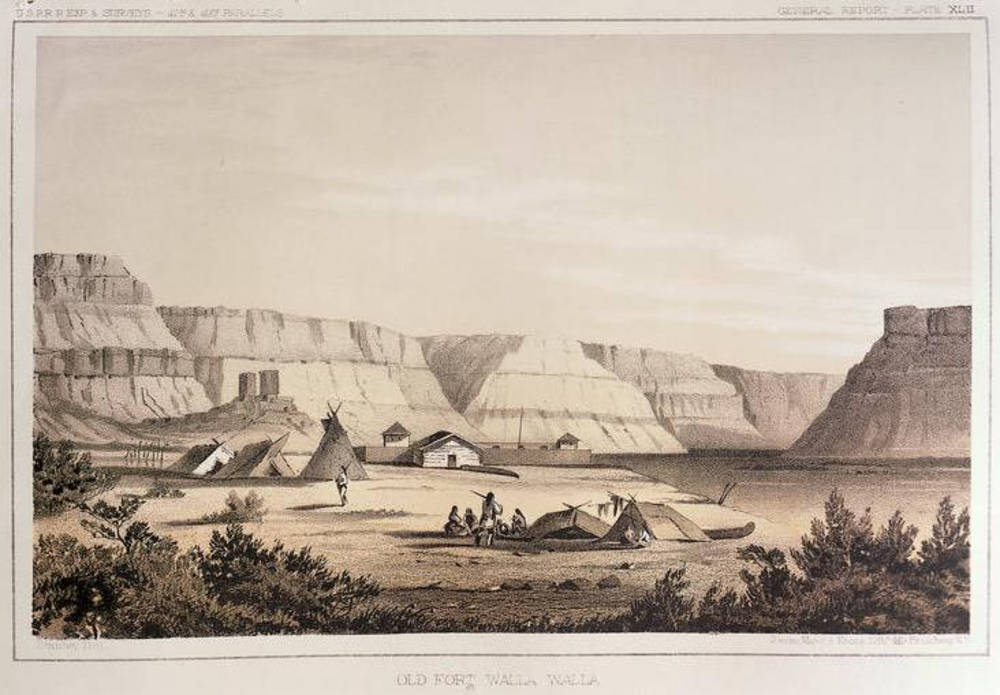

Nez Perce camp outside walls of Old Fort Walla Walla on the Columbia River, Washington, engraving made by John Mix Stanley in 1853.

Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, NA4169 -

![]()

Columbia River area Indian camp at The Dalles, engraving by John Mix Stanley, 1853.

Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, NA4170 -

![]()

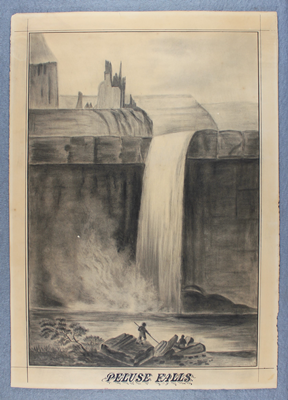

Charcoal sketch of Palouse Falls, by John Mix Stanley, c.1853.

Oregon Historical Society Museum Collection, 60-42.1

Related Entries

-

![Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)]()

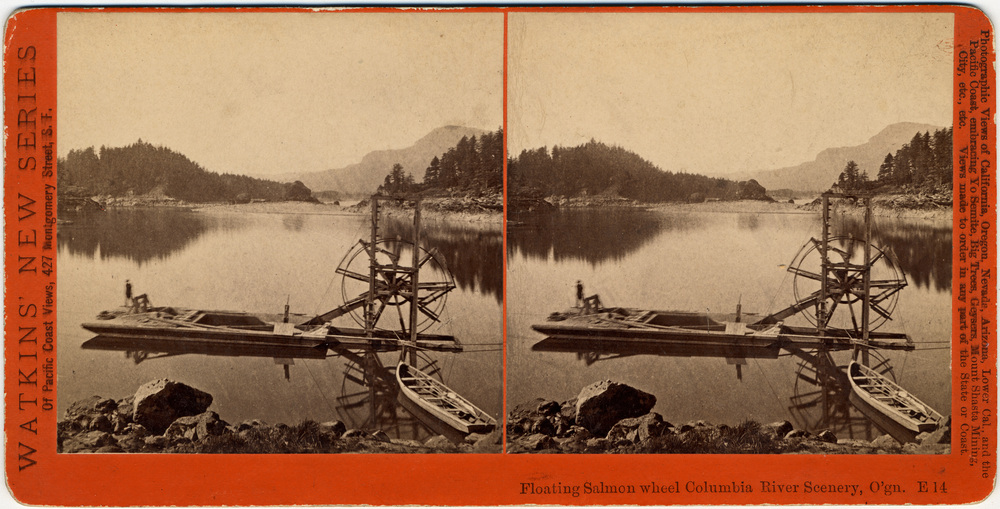

Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)

Carleton Emmons Watkins was a prominent San Francisco-based photographe…

-

![Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)]()

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)

Isaac Stevens strode through the Northwest's formative years (1853-1861…

-

![Oregon Historical Society]()

Oregon Historical Society

The Oregon Historical Society is a private museum, archival library, an…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Nicandri, David L. "Isaac I. Stevens and the Expeditionary Artists of the Northern West," in Encounter with a Distant Land: Exploration and the Great Northwest, edited by Carlos Schwantes. Moscow, ID: University of Idaho Press, 1994.

Nicandri, David L. "John Mix Stanley: Paintings and Sketches of the Oregon Country and Its Inhabitants." OHQ 88 (Summer, 1987).

Taft, Robert. Artists and Illustrators of the Old West: 1850-1900. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1953.