Seventeen-year-old Daiichi Takeoka arrived in Portland in 1900 with a limited education from his home in a rural section of Hiroshima, Japan. By the 1920s, his knowledge of the law and his fluency in English enabled him to begin a lifelong fight against discrimination. For decades, he acted as a bridge between cultures in Oregon, providing significant and sometimes critical support for Japanese immigrants and their families.

Like many other young Japanese men who immigrated to the Northwest during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Takeoka found work in construction on the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway and as a laborer for timber companies, likely getting jobs through a labor contractor in Portland. He also worked as a bellhop at the Portland Hotel.

Takeoka eventually enrolled at the University of Oregon, where he received a bachelor of law in 1912. Because Asian immigrants were prohibited from becoming naturalized citizens—the result of naturalization laws enacted in the United States in 1790—he was prohibited from becoming a licensed attorney, and throughout his life he partnered with white attorneys. In 1918, he married Kinuyo, a teacher from the Hiroshima prefecture. The couple lived in the Kerns neighborhood in northeast Portland and had five children. Takeoka supported the family by selling insurance and working for Swift & Company as a sales representative.

Daiichi Takeoka was a member of the Japanese Association of Oregon, which was established in 1911 to provide legal and financial assistance and social and educational services to the Japanese community. The Association also represented Japanese interests in Portland through its participation in community events such as the Rose Parade and charitable fundraisers. It worked to present a positive image of Japanese immigrants and their businesses and was a critical link between immigrants and the Japanese consulate. Takeoka was an interpreter and legal advisor for the organization and later served as the Association’s president.

Anti-immigration sentiment increased on the West Coast during the early twentieth century, much of it focused on Japanese. In May 1913, California Governor Hiram Johnson signed the California Alien Land Law, which tied ownership of land to eligibility for citizenship. Takeoka responded to the new restrictions in a letter to the Oregonian that included statistics showing how western states, including Oregon, benefited from trade with Asian countries. U.S. manufacturing was growing, he noted, and the country depended on and prospered from Japanese immigrant labor and contributions. An alliance between the two countries was advantageous to both, he argued, and he warned that such laws were a “blow to the welfare of the civilized world and to the cause of liberty.”

In a 1922 article in Oshu Nippo, Oregon’s Japanese-language newspaper, Takeoka urged Oregonians not to pass a similar law. He also gave advice to Japanese farmers. As the director of the Industry Division of the Japanese Association of Oregon, he had compiled data on agricultural land issues and discrimination against Japanese farmers, and he advised farmers to be thoughtful and deliberate in their actions, to work with trustworthy trading companies, and to expand their sales to other states.

Despite the efforts of Takeoka and others, in February 1923 the Oregon legislature prohibited the ownership or leasing of land by anyone who was not eligible for citizenship. During the three-month grace period before the law went into effect, Takeoka, as a Japanese Association representative, worked with attorneys in Oregon to help Japanese residents put their land in the name of their American-born children.

Takeoka also provided critical support to Japanese workers on the central Oregon Coast. In July 1925, the Pacific Spruce Corporation, a sawmill on the Oregon Coast in Toledo, hired a small team of Japanese workers. Two days after the new workers had arrived at the mill, a mob made up of local residents violently forced them and their families out of town. By October, five of the workers had filed separate civil lawsuits against nine of the Toledo attackers. Takeoka provided signed legal affidavits for four of the workers (who by then were employed in logging camps north of Portland), establishing their legal status in Oregon and making a trial possible. In a jury case, a Portland federal court found in favor of the plaintiff in the first case and awarded damages; an out-of-court settlement was reached in the other four cases. The decision and settlements were seen in both the U.S. and Japan as recognition that legal aliens in the United States had civil rights.

During the following decade, children of Japanese immigrants became adults, and some, like Takeoka's two oldest, enrolled in college. But Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, brought an abrupt end to everyday life for Japanese on the West Coast, and those who were not citizens were classified as “enemy aliens.” The FBI arrested Takeoka and other community leaders that the government considered potentially dangerous, and many of them spent the war years in Department of Justice prison camps. Takeoka was held at the camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In May 1942, Kinuyo Takeoka and their five children, ages ten to twenty-one, were sent to the Portland Temporary Detention Center and then to the Minidoka Incarceration Center in Idaho. The War Department announced the closing of the incarceration camps in December 1944, and people began returning to the western states in the following spring and summer. Daiichi and Kinuyo Takeoka and their youngest son were reunited in Portland in August 1945, a few weeks before Minidoka was officially closed in October. The four older Takeoka children had left Minidoka earlier for work or schooling.

In March 1945, Oregon Governor Earl Snell signed SB 274, a supplement to the 1923 Alien Land Law, preventing Japanese immigrants who were not U.S. citizens from living on and using land purchased in the name of a family member. The Committee for Oregon Alien Land Law Test Case was created in 1946 by a small group comprised of Issei (noncitizen immigrants) and Nisei (second-generation Japanese American citizens), with Takeoka as chair. Kennie Kenji Namba and his father Etsuo Namba agreed to be the plaintiffs in a test case, with Verne Dusenbery and Allan Hart as their attorneys. In 1949, in Kenji Namba v. McCourt, Oregon Chief Justice Hall S. Lusk declared that the state’s alien land laws violated both the Oregon Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment. That same year, the Oregon legislature repealed its alien land laws, the first state in the nation to do so.

Racial restrictions on naturalization were abolished with the passage of the Walter–McCarren Act in 1952, and Daiichi Takeoka became a United States citizen in February 1954. When he died on December 9, 1954, he was recognized as “one of the leaders of the Japanese community in Portland” and for “promoting friendship between Japan and the United States.”

-

![]()

Wedding picture of Daiichi and Kinuyo Takeoka, c. 1918.

Courtesy of the Yasui Family Collection, Densho Digital Repository -

![]()

Daiichi Takeoka, third from left, with friends and family in Hood River, c. 1915.

Courtesy Yasui Family Collection, Densho Digital Repository

Related Entries

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Japanese Ancestral Society]()

Japanese Ancestral Society

In the early 1900s, spurred on largely by railroad construction, farmin…

-

![Oshu Nippo]()

Oshu Nippo

For early Japanese immigrants to Oregon, a Japanese-language newspaper …

-

![Portland Temporary Detention Center (Portland Assembly Center)]()

Portland Temporary Detention Center (Portland Assembly Center)

From May 2 to September 10, 1942, an eleven-acre building on the south …

-

![Toledo Incident of 1925]()

Toledo Incident of 1925

In 1925, a mob forced a Japanese labor crew to leave Toledo, a communit…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Anderson, Emily. "Japanese associations." Densho Encyclopedia.

Azuma, Eiichiro. “A History of Oregon’s Issei, 1880-1952.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 94.4 (Winter 1993–1994): 315-367.

Buck, Amy K. “Alien Land Laws: The Curtailing of Japanese Agricultural Pursuits in Oregon.” Portland State University, Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3988. 1999.

Buck, Amy. “Alien Land Laws in Oregon, 1923-1949.” Willamette Journal of the Liberal Arts, Supplemental Series 7 (2000).

Burton, Jeffrey F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites: Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

Chuman, Frank. The Bamboo People: The Law and Japanese-Americans. Chicago: Japanese American Citizens League, 1981.

Cox, Ted. The Toledo Incident of 1926: Three Days made History in Toledo, Oregon. Corvallis. Ore.: Old World Publications, 2005.

Ito, Kazuo. Issei: A History of Japanese Immigration in North America. Seattle, Wash.: Japanese Community Service, 1973.

Iwata, Masakazu. Planted in Good Soil: A History of the Issei in U.S. Agriculture. New York: Peter Lang, 1992.

Robinson, Greg. "Kenji Namba v. McCourt." Densho Encyclopedia.

McWilliams, Carey. PREJUDICE Japanese Americans: Symbol of Racial Intolerance. Boston. Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1944.

"Bill Banning Alien Japs as Land Owners Signed." Oregon Journal, March 27, 1945.

“Charles D. Takeoka.” Oregonian, December 15, 1954.

“‘Father of Our Country’ Would be Proud of Them.” Oregonian, February 23, 1954.

“Japanese Honor Chas. Takeoka.” Oregonian, December 25, 1954.

“Legion Will Urge Alien Land Law.” Oregonian, March, 3, 1922.

“Snell Signs Alien Bill.” Oregonian, March 28, 1945.

Stearns, Marjorie. The History of Japanese People in Oregon. San Francisco: R and E Research Associates, 1974.

Takeoka, Daiichi. "Letter to the editor." Oregonian, June 7, 1913, 8.

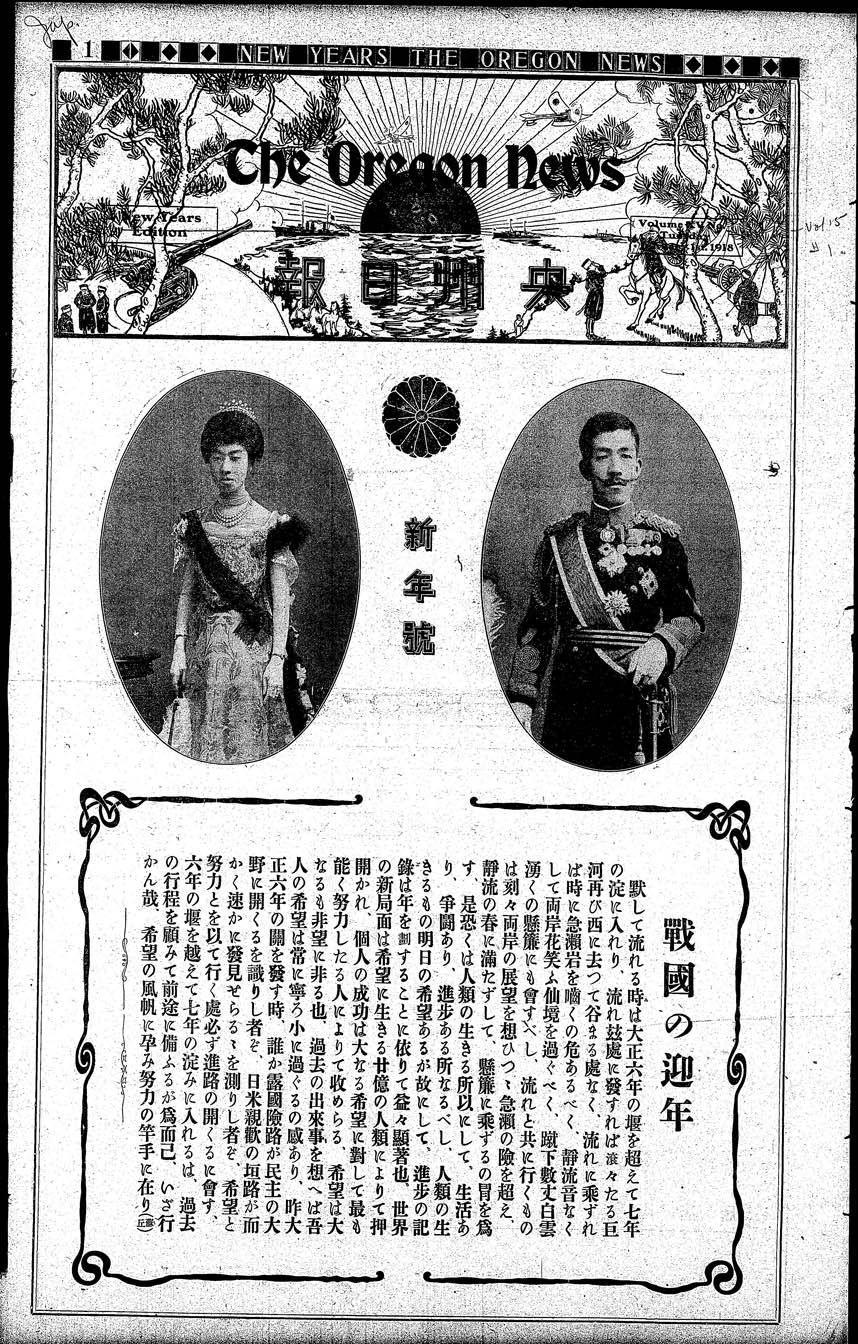

–––––. “Japanese and American Agriculture and the Future of Agriculture for the Japanese Living in Oregon” Oshu Nippo, New Year’s Special 1922, JAMO Archives.

Takeoka, Tom. Letter to Becky Patchett, JAMO Archives, 2007.

Yasui, Barbara. “The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834-1940.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 76.3 (1975): 225-257.