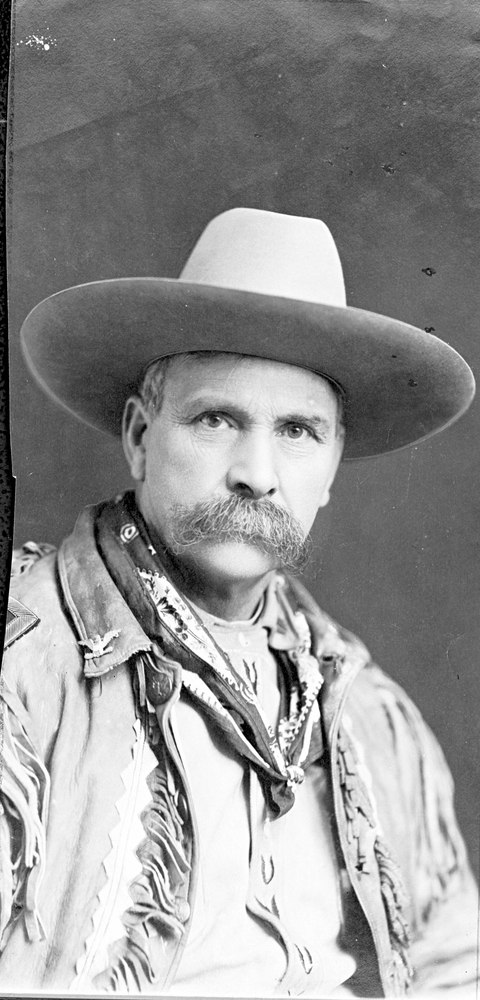

Oregon photographer Thomas Leander Moorhouse of Pendleton, Oregon, was a multifaceted man. Born in 1850 in Marion County, Iowa, he moved with his family to Walla Walla, Washington, in 1861 in an ox-drawn wagon. He was a miner, surveyor, rancher, businessman, civic leader, Umatilla Indian agent, real-estate operator, insurance salesman, and assistant adjunct general of the Oregon State Militia, where he achieved the rank of major.

Like many Americans, Moorhouse took up photography in the 1880s after George Eastman made an easy-to-use film camera. Unlike most amateur photographers, however, he worked with glass-plate negatives, large cameras, and a tripod—the equipment of professional photographers. From 1888 to 1916, he produced over 10,000 images documenting Native American cultures and the urban and rural lives of his white contemporaries in eastern Oregon and Washington. So extensive and revealing are Moorhouse's images that his work constitutes one of the preeminent social history collections for life east of the Cascades during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

About one-third of Moorhouse's images are concerned with Native peoples, and they fall into two broad categories: studio portraits of tribal members, which he often made in the backyard of his home, and images of life on the Umatilla Reservation. During his lifetime, Moorhouse was most celebrated for his studio portraits. For example, his portrait of the Cayuse Twins, near Wallula Gap, reportedly sold over 150,000 copies.

Many recent scholars find Moorhouse's studio images unsatisfactory because they are stiffly posed and the photographer drew from his extensive collection of Native American artifacts to supply the clothing people wore and the implements they held. But Moorhouse also took pictures that documented the life experiences of Native peoples. Some of his photographs taken on the Umatilla Reservation, for example, are reliable sources of information on Native clothing and dwellings, and they capture some of the social and cultural transformations that people there were experiencing.

Other photographs that Moorhouse took on the reservation and certainly the studio portraits—much like those of his acquaintance Edward S. Curtis—propagated the view that Indians were a vanishing race. One of Moorhouse's goals was to preserve on film the last shimmerings of Indian traditions before they passed into oblivion. This notion, as many have pointed out, presents a selective image of Native American life, one that extols and idealizes the past but fails to deal with present experiences. Both the portraits and the images from the reservation have recently been recognized as valuable for eliciting memories among tribal elders. Anthropologist Deward E. Walker persuasively has made the point that such memories have helped reveal important events that normally escape the attention of academic historians.

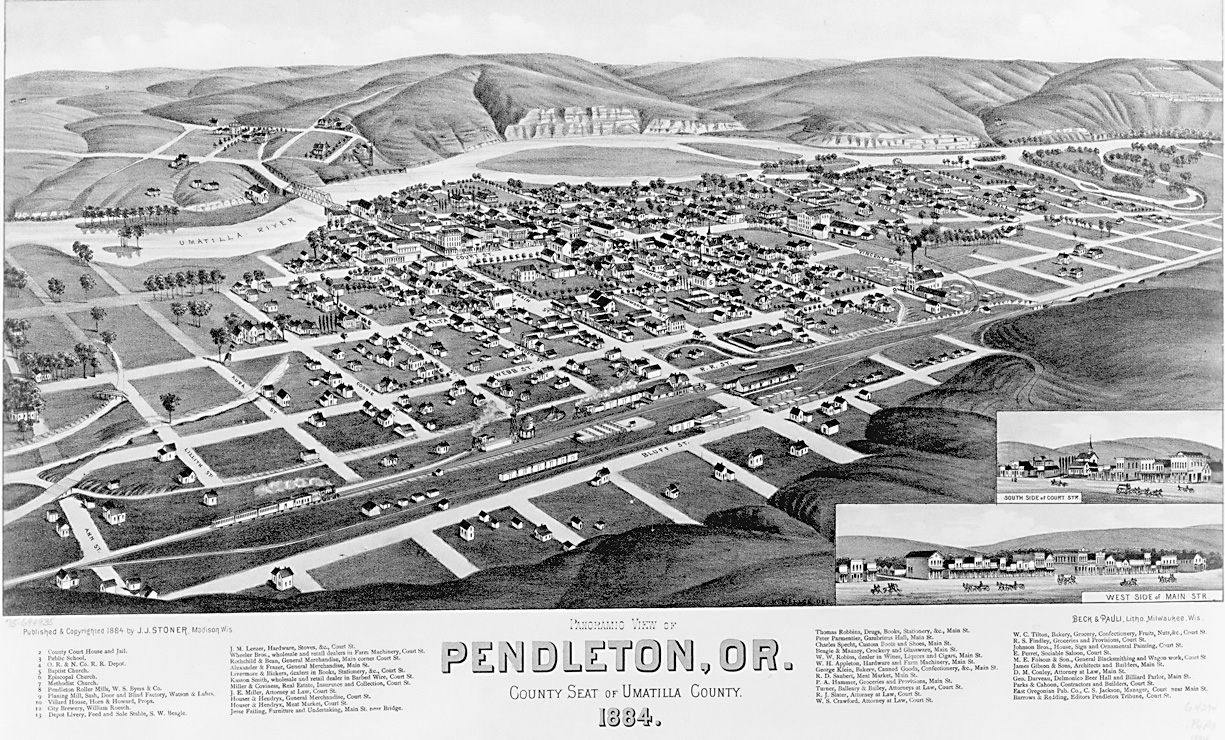

By far the largest group of Moorhouse photographs shows scenes of daily life, both rural and urban, of his white contemporaries east of the Cascades. During his lifetime, the area around Pendleton was exploding economically and experiencing tremendous population gains. Moorhouse's photographs celebrate the prosperous development of the West and document ranchers and their homes along with itinerant laborers and their work in the fields. He produced thousands of images of small town and community life, including views of businesses, schools, churches, logging operations, and forms of transportation. Moorhouse was particularly interested in the social life and entertainments of his contemporaries, and he frequently photographed circuses, parades, and Wild West shows. He also made over 600 images of the Pendleton Round-Up from 1910 to 1919.

Throughout his life, Moorhouse was careful to describe himself as an amateur for whom collecting Native American artifacts and photographing the world around him was a hobby. A close look at the full body of his work, however, makes plain that he had a keen eye and an intense interest in his world and a deep interest in history and in creating a historical record.

A serious photographer, Moorhouse sent a message in every image. His photographs are poignant and revealing reports on an era, a region, and its peoples. Without his photographs, our understanding of this important period in Oregon history would be diminished.

-

![]()

Thomas Leander Moorhouse.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library bb003725

Related Entries

-

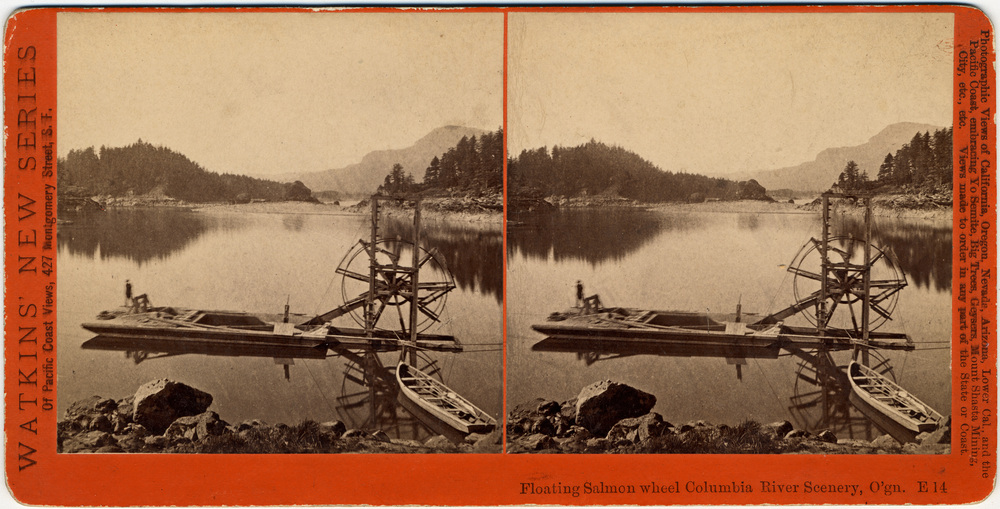

![Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)]()

Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)

Carleton Emmons Watkins was a prominent San Francisco-based photographe…

-

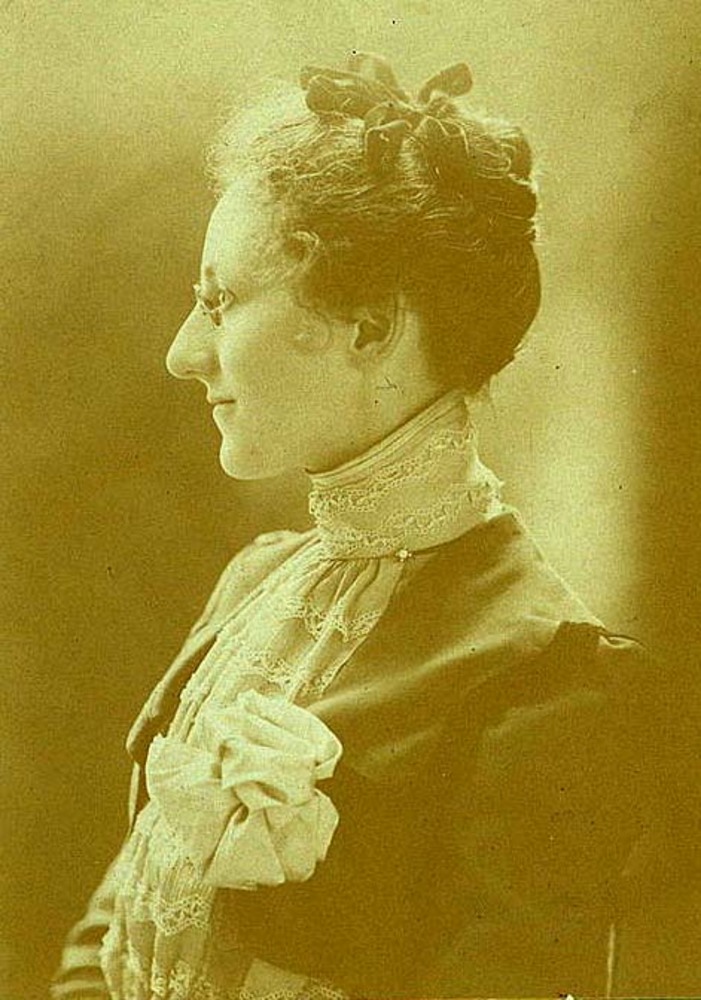

![Myra Albert Wiggins (1869-1956)]()

Myra Albert Wiggins (1869-1956)

Myra Albert Wiggins was a painter and photographer who gained recogniti…

-

![Pendleton]()

Pendleton

Pendleton, a city of 17,107 in the 2020 census, sits in the foothills o…

-

![Pendleton Round-Up]()

Pendleton Round-Up

The Pendleton Round-Up began in September 1910 as a frontier exhibition…

-

![Robert Adams (1937-)]()

Robert Adams (1937-)

Robert Adams’s photographs of the American West are incisive view…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Grafe, Steven L. Peoples of the Plateau: The Indian Photographs of Lee Moorhouse, 1898–1915. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005.

Sandweiss, Martha A. “Picturing Indians: Curtis in Context." In The Plains Indian Photographs of Edward S. Curtis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Schmitt, Martin. “The Moorhouse Photographic Collection." The Call Number 15:1 (December 1953).

Walker, Deward E. “The Moorhouse Collection: A Window on Umatilla History." In The First Oregonians. Edited by Carolyn M. Buan and Richard Lewis. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 1991.