In 1929, Portland was a city deeply divided. Its small population of African Americans lived uneasily among their white neighbors. Only three years had passed since Oregonians had voted to amend their constitution to allow Blacks to permanently settle in Oregon, and there was little employment open to African Americans. By tacit agreement among business and political leaders, the vast majority of Blacks worked for railroads and hotels. Into this milieu stepped thirty-year-old African American physician DeNorval Unthank, who would become one of the city’s most visible civil rights activists.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1899, Unthank was raised from the age of nine by his aunt and uncle in Kansas City. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan, which had been educating African Americans since 1868 and had accepted Black students into its medical program as early as the 1880s. With such role models to encourage him, Unthank chose to attend the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C. He received his M.D. in 1926.

Unthank was recruited to Oregon by the Union Pacific Railroad and its local physician, James A. Merriman. A 1902 graduate of Rush Medical College, Merriman had been brought to Portland by Union Pacific in 1903 because the railroad required a Black physician to care for its Black workers. When Merriman moved to Arizona in 1931, Unthank became the only Black physician in Portland.

Upon his arrival in 1929, Unthank was harassed so mercilessly by the whites in his neighborhood that his family was forced to move. The family relocated four times before finding a home on Southeast 29th Street where they could live peacefully. Challenged as well by the economic downturn, Unthank expanded his practice to serve not only the Black community but also Asians and whites. Many of his early patients were loggers, since, as he later noted, “they were about the only people working during the Depression.” By the time of his retirement, about half of Unthank’s patients were white.

Witness to and the victim of rampant discrimination, Unthank began to devote much of his energy to improving race relations in Portland, leveraging his position as a trusted professional to speak out about discriminatory practices. In 1940, he led a group called the Emergency Advisory Council, which sought to force local government to provide equal opportunity to wartime employment and business contracts.

During a time of great change, as the city’s Black population grew from roughly 2,000 to 20,000 between 1941 and 1943, Unthank became the first African American member of the Portland City Club. He was a cofounder of the Portland Urban League in 1945 (donating his examination room for the League office) and served as president of the Portland chapter of the NAACP. He was also a member of the state Committee for Equal Rights and the Council of Social Agencies and was active in the passage of the state’s 1953 Civil Rights Bill. At Unthank’s death, Urban League Director Sheldon Hill said: “Contributions he has made to the community over 50 years have a lot to do with the direction race relations have taken in this town.”

In 1958, Unthank was named Doctor of the Year by the Oregon State Medical Society in recognition of his civic leadership. The recognition was but one in a long line of awards. In 1962, he was named Citizen of the Year by the Portland chapter of the National Conference of Christians and Jews for his work with the local Romani community. In 1971, he received the distinguished citizenship award from the University of Oregon and the Distinguished Achievement Award from the Metropolitan Human Relations Commission. In 1973, he was honored with the Brotherhood Award from the Portland chapter of B’nai B’rith.

In 1969, the city of Portland dedicated a park on North Shaver Street to Dr. Unthank in commemoration of his years of activism in humanitarian efforts. He was at that time the only living Portland citizen to have such a space named after him, and he is still the only physician to have been so honored. Unthank officially retired from practice in 1970. He died on September 20, 1977.

Unthank was often quoted as saying: “I have always felt in my life that a person should set his own goals and then head toward them. You may have some bad experiences along the way, but if you’re determined you can make it. A Negro may have a few more doors closed to him and he may find them a little harder to open, but he can open them. He must keep trying.”

-

![]()

-

![]()

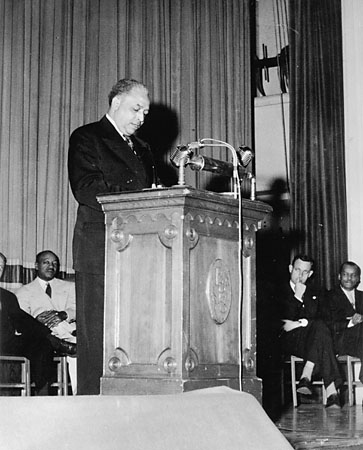

DeNorval Unthank, 1967.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Edwin C. (Bill) Berry (1910–1987)]()

Edwin C. (Bill) Berry (1910–1987)

Bill Berry, a leader in the Urban League for nearly thirty years, was t…

-

![Nathalie McDowell Johnson (1959-)]()

Nathalie McDowell Johnson (1959-)

Dr. Nathalie McDowell Johnson, a dancer and physician, moved to Oregon …

-

![William McClendon (1915-1996)]()

William McClendon (1915-1996)

William McClendon was a writer, journalist, intellectual, activist, and…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

History of Portland’s African American Community (1805-to the present). Portland, Ore.: Portland Bureau of Planning, 1993.

Pearson, R.N. "African Americans in Portland, Oregon, 1940-1950: Work and Living Conditions--A Social History." Ph.D. dissertation, Washington State University, 1996.