Established in 1849, Vancouver Barracks played a pivotal role in regional, national, and international military operations for nearly a century. The first U.S. Army post in Oregon Territory, its strategic location on the north side of the Columbia River (in present-day Vancouver, Washington) enabled it to serve as an administrative, supply, and support center to protect American interests in the region. Known in its first year as Camp at Fort Vancouver, Camp Columbia, Camp Vancouver, and Fort Vancouver, the post was officially designated Columbia Barracks in 1850, Fort Vancouver in 1853, and finally Vancouver Barracks in 1879.

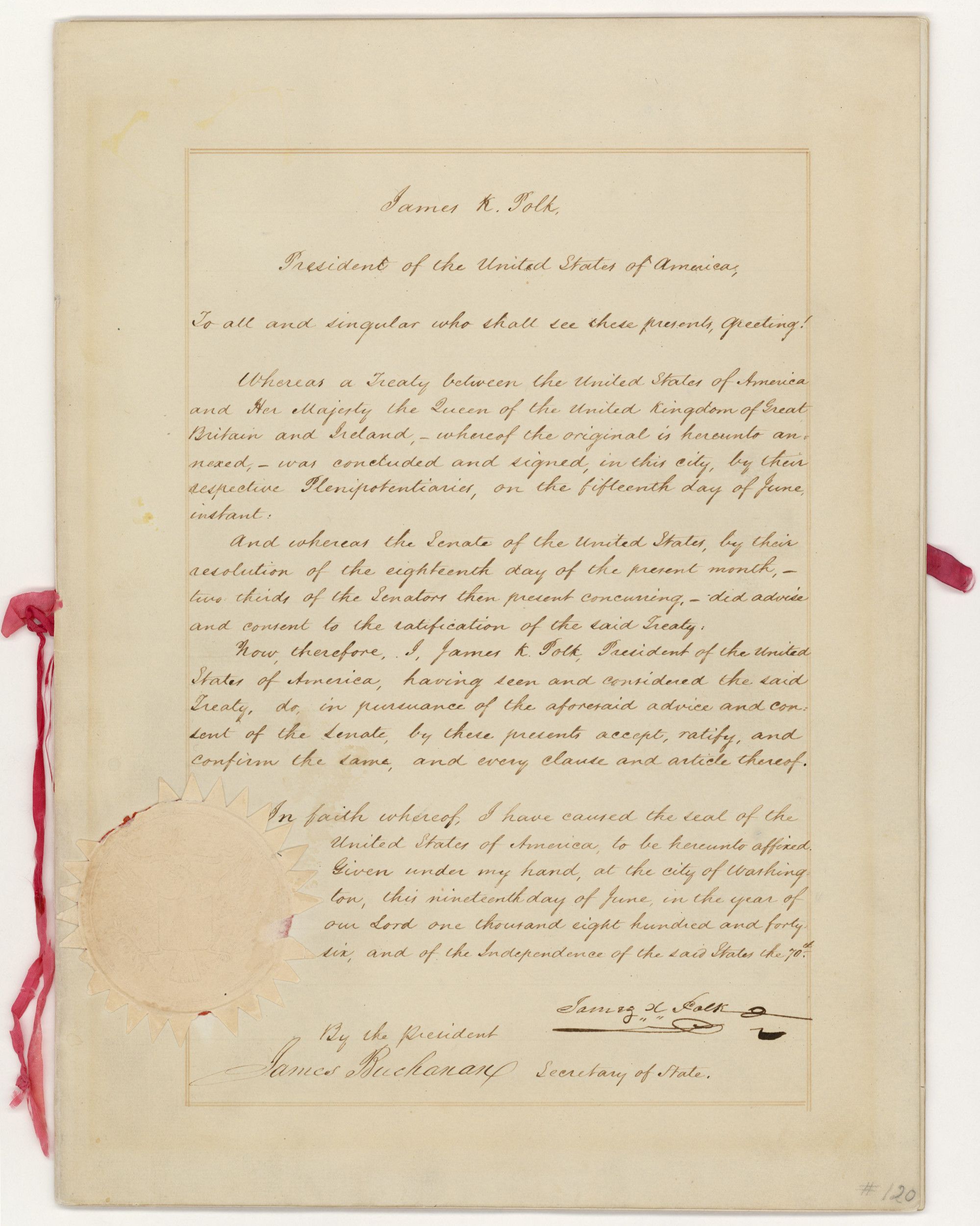

The army established a camp at Fort Vancouver, the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company, following the 1846 resolution of the Oregon boundary dispute between Great Britain and the United States and in response to increasing conflict between American resettlers and Native peoples. Soldiers arrived in 1849 and built a post on the plain overlooking the British fur trade fort. Barracks, officers’ quarters, the company commander’s house (preserved on Officers Row as the Grant House), and other buildings were constructed, forming an open rectangle centered on the garrison flagpole and parade ground. From that basic design, Vancouver Barracks was expanded up into the twentieth century, serving as an economic engine and driving commerce and development throughout the region.

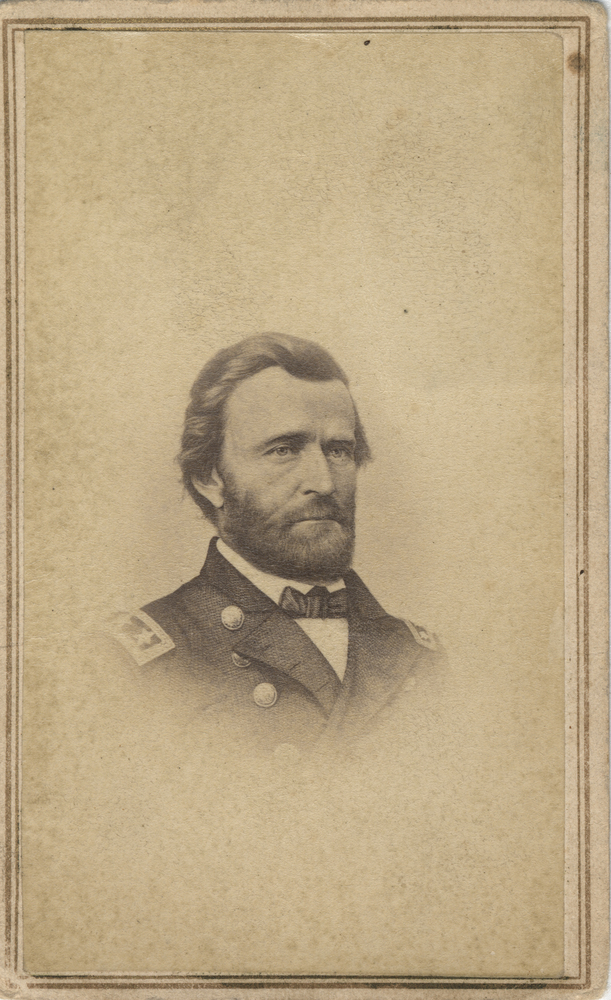

During the nineteenth century, Vancouver Barracks was one of several independent commands within a broader military reserve that included the Vancouver Depot (a quartermaster’s depot) and the Vancouver Ordnance Depot, later the Vancouver Arsenal. The post also hosted the U.S. Army’s department and district headquarters, first from 1850 to 1866 and then from 1879 through the end of the nineteenth century. During the Civil War, volunteer units garrisoned the fort after its regular troops were transferred to the East. Several significant military and political leaders served at the post, including Ulysses S. Grant, Oliver O. Howard, and George C. Marshall.

While no battles occurred at Vancouver Barracks, the post provided military support for many conflicts against Native peoples, including the Rogue River Wars, the Yakima War, the Paiute War, the Snake Wars, the Modoc War, the Nez Perce War, the Bannock (Paiute) War, and the Sheepeater (Shoshone) War. During this period and beyond, the U.S. Army also imprisoned Native people at the post, including members of Nez Perce, Paiute, Yakama, and Sheepeater bands. Commanders such as General Howard used the threat of imprisonment at the post as policy to destabilize tribal resistance.

Soldiers from Vancouver Barracks were dispatched to other conflicts as well. They protected Chinese workers during labor disputes in Seattle in 1885–1886, suppressed labor-related violence in Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene mining wars in 1892 and 1899, guarded railroad trains and property of the Northern Pacific Railroad during the Pullman Strike of 1894, and prevented civil disorder during the Klondike Gold Rush in the Yukon (1898). The post also provided soldiers and supplies for the construction of roads—including the Mullan Road and other roads between Vancouver, The Dalles, and the Great Salt Lake Valley in 1859—and the survey of the transcontinental railroad in 1853. In 1880, officers started a post canteen store at Vancouver Barracks to keep soldiers away from the bars in the City of Vancouver. The store provided food and drinks and a place for relaxation and games and was the predecessor of the present-day Post Exchange system.

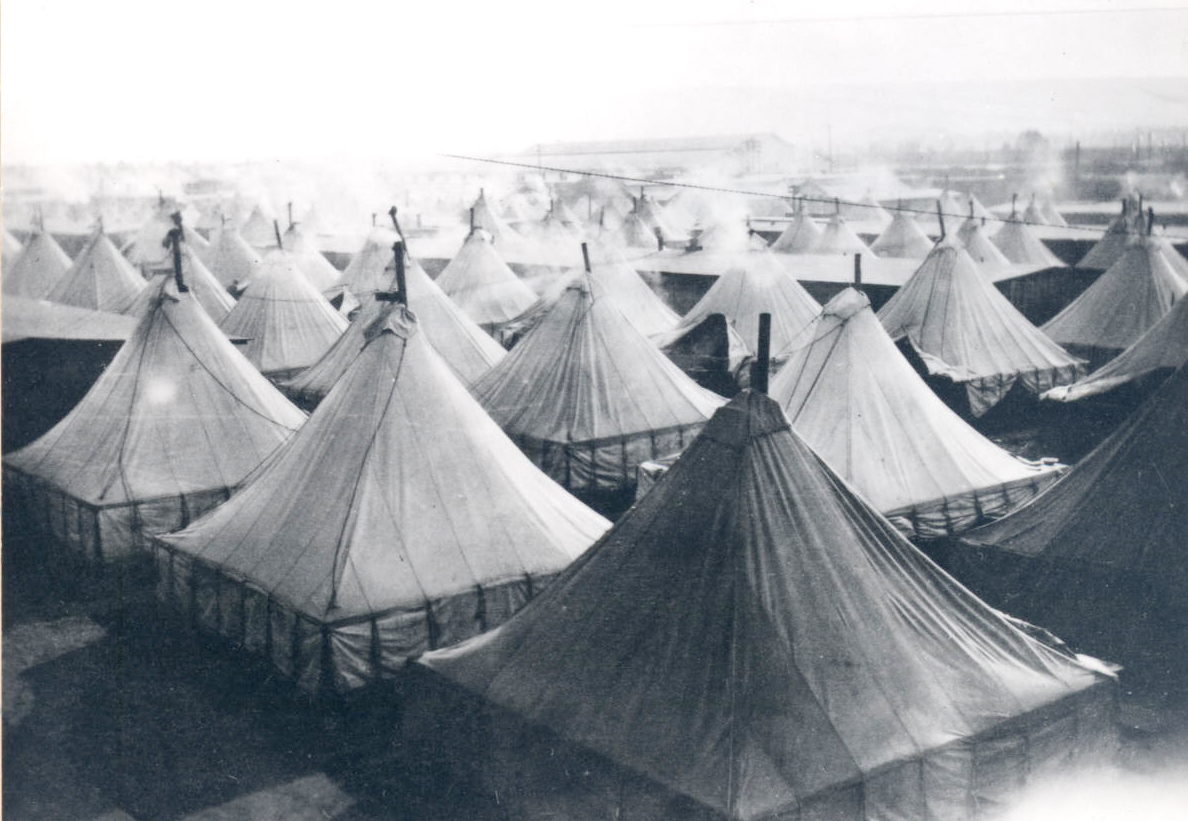

During both the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), Vancouver Barracks was a training center and an overseas mobilization point for recruits. During World War I, the post was designated as one of three engineer training camps in the United States. Sitka spruce lumber was integral to the construction of wartime aircraft, and the army constructed the Spruce Cut-Up Mill at the post in 1917 under the direction of the Spruce Production Division; it was the world’s largest such mill at the time.

The spruce mill was razed after the war, and the post became an early center for Army Air Corps aviation, centered on Pearson Field. A Citizens Military Training Camp was established in the 1920s to prepare men for military service, and in the 1930s the post was headquarters for the Ninth Corps District of the Civilian Conservation Corps, which supported as many as fifty-five camps in the region.

During World War II, Vancouver Barracks operated as a training center and staging area for the Portland Subport of Embarkation, aiding the movement of supplies and troops to the war’s Pacific Theater. At the war’s end, the post was declared surplus, and the City of Vancouver and the National Park Service (NPS) acquired post acreage through the War Assets Administration. The property administered by the NPS became the Fort Vancouver National Monument in 1948; it was renamed the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site in 1961. The U.S. Army retained some acreage as a center for reserve training and as the headquarters of the 104th Reserve Infantry Division. The City of Vancouver acquired Officer’s Row in 1980 and the West Barracks in 2008.

Congress established the Vancouver National Historic Reserve in 1996 to include the sections of the post owned by the National Park Service and the City of Vancouver. In 2007, the Fort Vancouver National Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The U.S. Army Reserve relinquished the remaining East and South Barracks parcels to the Park Service in 2012. Consistent with its 2012 master plan, the area is administered as part of the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site to “create a dynamic, sustainable, public service campus where the history of the East and South Barracks is preserved and interpreted.” Sustainability, historic preservation, and rehabilitation are modeled through adaptive reuse of the buildings and resources.

-

![]()

Vancouver Barracks, c.1915.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 67837

-

![]()

Vancouver Barracks.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 57521

-

![From the Boundary Commission Survey, 1860-1861. Photo from the Royal Engineers Library in Kent, England.]()

Fort Vancouver, c.1860.

From the Boundary Commission Survey, 1860-1861. Photo from the Royal Engineers Library in Kent, England. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Lot 556

-

![Back row: Sgt. Bogue, Brown, Shultz, Capt. Patrick, Sgt. Roth

Front: Walsh, Hammer, Merwin, Barnes, Capt. Rogers.

The referred to themselves as "The Suicide Club."]()

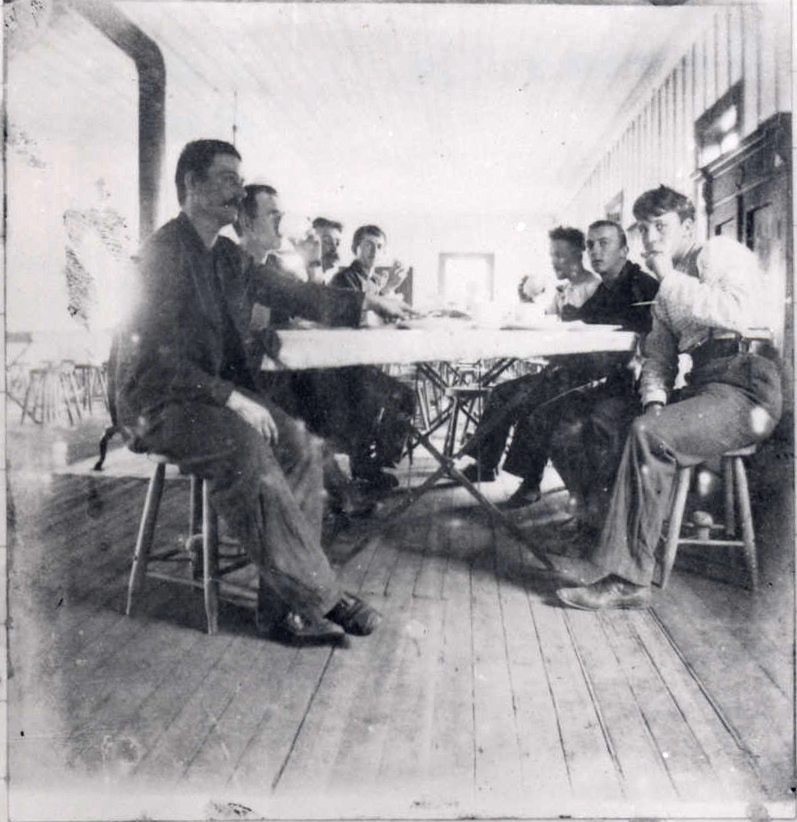

Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks, c 1898.

Back row: Sgt. Bogue, Brown, Shultz, Capt. Patrick, Sgt. Roth Front: Walsh, Hammer, Merwin, Barnes, Capt. Rogers. The referred to themselves as "The Suicide Club." Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 72633

-

![]()

Oregon Volunteers, Battery A, Vancouver Barracks, c. 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019963

-

![Soldiers perform for the camera]()

Oregon Volunteers, Battery A, Vancouver Barracks, c. 1898.

Soldiers perform for the camera Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019964

-

![]()

Post ambulance, Fort Vancouver, c.1898.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 72636

-

![]()

Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks, c 1915.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 982d172

-

![]()

Vancouver Barracks, c.1915.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi74798

-

![]()

Vancouver Barracks, 1940.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Al Monner news negatives; Org. Lot 1284; Box 8; 188-24 -

![]()

Buildings at Vancouver Barracks, 1940.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Al Monner news negatives; Org. Lot 1284; Box 8; 188-18 -

![]()

Army band at Vancouver Barracks, 1943.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Al Monner news negatives; Org. Lot 1284; Box 20; 777-10

Related Entries

-

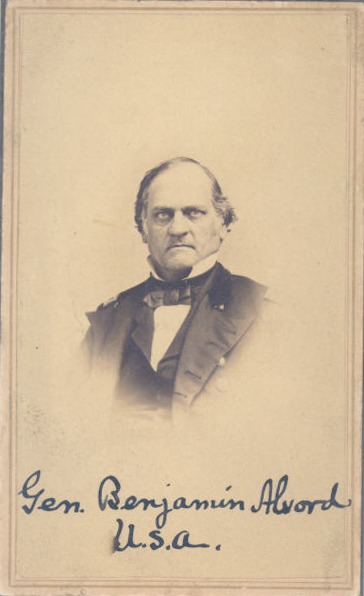

![Benjamin Alvord (1813-1884)]()

Benjamin Alvord (1813-1884)

An army officer, educator, writer, and naturalist, Benjamin Alvord was …

-

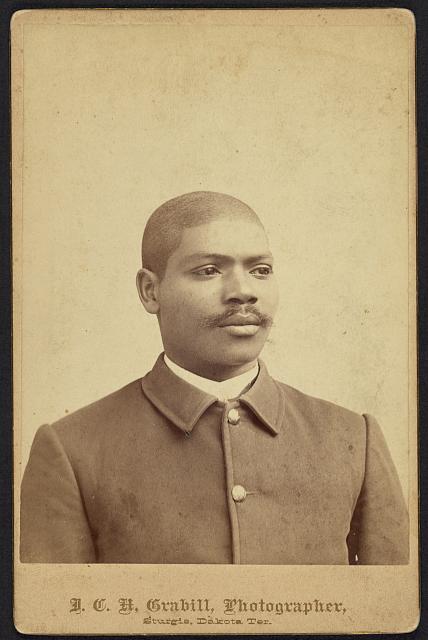

![Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks]()

Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks

For thirteen months beginning in 1899, a company of 103 soldiers from t…

-

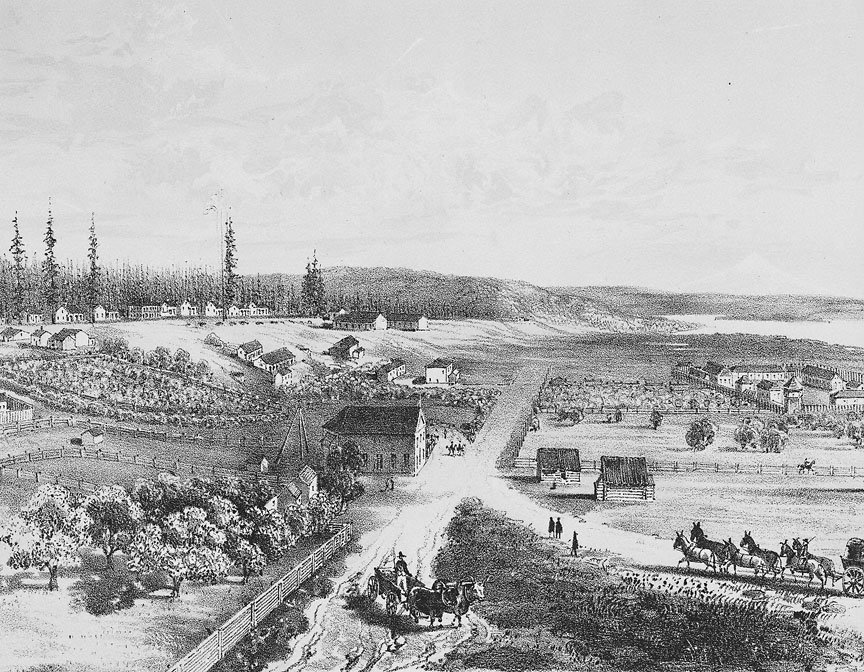

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Moses Williams (1845-1899)]()

Moses Williams (1845-1899)

Born in rural Louisiana in 1845, Moses Williams joined the U.S. Army in…

-

![Oregon Treaty, 1846]()

Oregon Treaty, 1846

On November 12, 1846, the Oregon Spectator announced that Captain Natha…

-

![Spruce Production Division]()

Spruce Production Division

In 1918, during World War I, almost thirty thousand U.S. soldiers were …

-

![Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)]()

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)

Ulysses S. Grant, a native of Ohio, graduated from the U.S. Military Ac…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"Vancouver Barracks." National Park Service website.

--- "Part II, The Waking of a Military Town: Vancouver, Washington and the Vancouver National Historic Reserve, 1898-1920." Vancouver, Wash.: National Park Service, 2005.

--- "Part III, Riptide on the Columbia: A Military Community Between the Wars, Vancouver, Washington and the Vancouver National Historic Reserve, 1920-1942." Vancouver, Wash.: National Park Service, 2005.

Van Arsdol, Ted. Northwest Bastion: The U.S. Army Barracks at Vancouver, 1849-1916. Vancouver, Wa.: Heritage Trust of Clark County, 1991.

Hatheway, John S. Frontier Soldier: The Letters of Maj. John S. Hatheway, 1833-1853. Edited by Ted Van Arsdol. Vancouver, Wa.: Vancouver National Historic Reserve Trust, 1999.

Babalis, Timothy. The Physical Development and Historical Context of the East and South Barracks, Vancouver Barracks, Washington. Vancouver, Wa.: National Park Service, 2012.

Deur, Douglas. An Ethnohistorical Overview of Groups with Ties to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. Seattle, Wash.: Pacific Northwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit National Park Service, Pacific West Region, 2012.

Shine, Gregory P. “Respite from War: Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks, 1899-1900." Oregon Historical Quarterly 107.2 (Summer 2006): 207-209.