In its short history, from 1942 to 1948, Vanport was the nation’s largest wartime housing development, a site for social innovation, a lightning rod for racial prejudice, and the scene of one of Oregon’s major disasters.

Between 1940 and 1943, defense employment in the Portland and Vancouver area climbed from a few thousand to about 140,000 in late 1943 and early 1944. Three Kaiser Company shipyards accounted for 92,000 of the total, and other shipbuilding and ship-repair businesses for 23,000 more. The influx of workers and their families put severe strain on housing supply, making it difficult to secure and hold skilled workers.

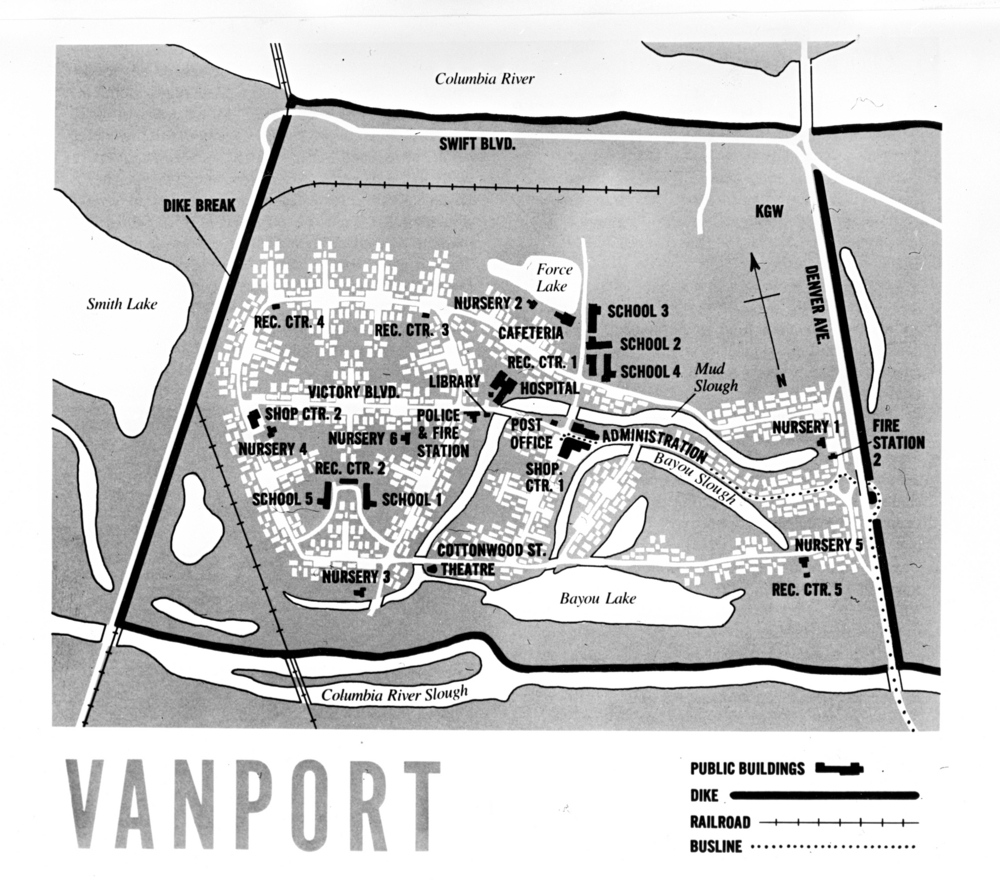

In response, Edgar Kaiser worked with the U.S. Maritime Commission and inked a deal to secure funding for a massive housing project. The commission formally approved the project on August 18, 1942. The site was 650 acres of the Columbia River flood plain west of Denver Avenue and east of the North Pacific railroad line, a location that was roughly equidistant between Kaiser facilities at Swan Island, St. Johns, and Vancouver.

Portlanders who had not been privy to the negotiations were surprised when contractors broke ground and a workforce that grew to 5,000 men and women swarmed over the site, grading roads and setting foundations. Board members of the new Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) grumbled about being left in the dark, but they agreed to take over management of the project.

Known as Kaiserville, the project received its official name of Vanport in November 1942, taken from the two cities on either side of the Columbia River—Vancouver and Portland. The first tenants arrived on December 12, 1942.

Original plans called for 6,022 apartments. The commission expanded the number to 9,922 when the project was only three days old (20 more were eventually added). Nearly all of the apartments were in fourteen-unit buildings. Built of wood on wooden foundations—a challenge in the swampy site—the buildings were two-story boxes with one-story wings. The standard apartment had a living room with kitchenette, bathroom, and one bedroom. Each set of four buildings shared a common utility building with a coal furnace, hot water heater, laundry room, and bathtub (the individual apartments had showers). In addition, HAP built 484 units in a separately developed but adjacent East Vanport. The muddy, grey-painted community was far from beautiful and struck one writer as “a glorified auto camp 100 times enlarged.”

Because Vanport was outside Portland city limits, the HAP created its own ad hoc and unofficial city government. It oversaw creation of an independent fire district and school district that provided day care as well as classroom instruction. The Multnomah County Sheriff’s Department provided law enforcement. J.L. Franzen, former city manager for Oregon City, administered fire protection and recreation services.

As the second-largest city in Oregon, Vanport had shopping centers, a 750-seat movie theater that offered three double features a week, a 150-bed hospital, recreation centers, schools, and nurseries that provided twenty-four-hour care for the children of working parents. Day care provided by the school district came with dinner and breakfast for children aged two to twelve. There were also prepared meals that working women could pick up on their way home from work.

Social work staff set up tenant councils, but HAP limited them to advisory functions. The Authority was cautious about a proposal for a community newspaper, which it feared would accentuate any problems. At the same time, the community contained a core of progressive and left-leaning activists who had some success in organizing among tenants.

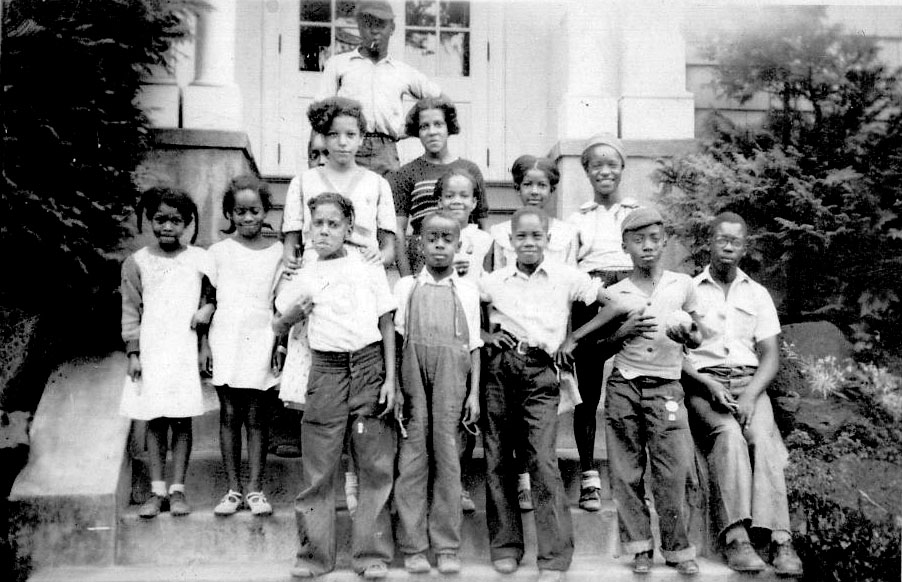

Vanport was racially segregated. For the record, HAP stated that the clearly demarcated color lines there and at smaller war-housing projects were the result of free choice among available apartments, but tenants were steered to different sections on the basis of race. Vanport’s Black residents found integrated schools but segregated medical facilities. They also faced nasty incidents when the sheriff’s office tried to enforce informal segregation of recreational facilities, claiming that mixed use might lead to trouble. As late as February 1945, the Housing Authority and city and state officials met to discuss “the possibilities, effects and desirability of various types of housing to be restricted to negro occupancy.”

Vanport’s occupancy reached a peak of 9,367 units in January 1944, dropped slightly, and then climbed to 9,568 units in December 1944, when its total population was approximately 42,000. The population slowly fell toward the end of the war.

With victory approaching, civic leaders debated Vanport’s future. Although it provided ready housing for returning veterans, many leaders hoped to demolish the apartments to make room for industrial development. The HAP board decided that “the district, distinct advantages and desirability of Vanport City for comprehensive industrial development, inspire us with the challenging hope that we may concern what might have been a troublesome blighted area into a constructive community asset.”

Many who remained were African Americans (6,000 as of V-J Day), who found it difficult to secure other housing. Vanport gained a whispered reputation for welfare clients and crime, although the recorded crime rate was no higher than the rest of the city. Mayor Earl Riley called it a “great headache” and a “municipal monstrosity.” At the same time, many Portlanders came to the community for classes at the Vanport Extension Center of the Oregon State System of Higher Education, the predecessor of Portland State University.

The Columbia River intervened on Memorial Day, May 30, 1948. Swollen by weeks of heavy rain, the river at Portland crested fifteen feet higher than its flood plain, held back only by dikes. At 4:17 p.m., the water breached the Northern Pacific Railway embankment and backfilled the low-lying community. While water filled sloughs and low spots, the community’s 18,500 residents had thirty-five minutes to escape. The rising water tumbled automobiles and swirled Vanport’s wooden apartment buildings off their foundations like toy boats. Fifteen residents died.

Refugees crowded into Portland, a city still recovering from the war. Part of the problem was racism, for more than a thousand of the flooded families were African Americans who could find housing only in the growing ghetto in North Portland. The flood also sparked unfounded but persistent rumors in the African American community that the Housing Authority had deliberately withheld warnings about the flood and the city had concealed a much higher death toll.

In the following years, the Vanport site surfaced in 1953-1954 as a possible location for a Memorial Coliseum before a more centrally located site was chosen. The site is now occupied by West Delta Park, Portland International Raceway, and Heron Lakes Golf Course.

-

![]()

Aerial view of Vanport.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 56002

-

![]()

Vanport Daily Vacation Bible School, 1943.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 78867

-

![Carl Downey carries a woman to safety in aftermath of the flood, May 30, 1948.]()

Vanport Flood, 1948.

Carl Downey carries a woman to safety in aftermath of the flood, May 30, 1948. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 3623

-

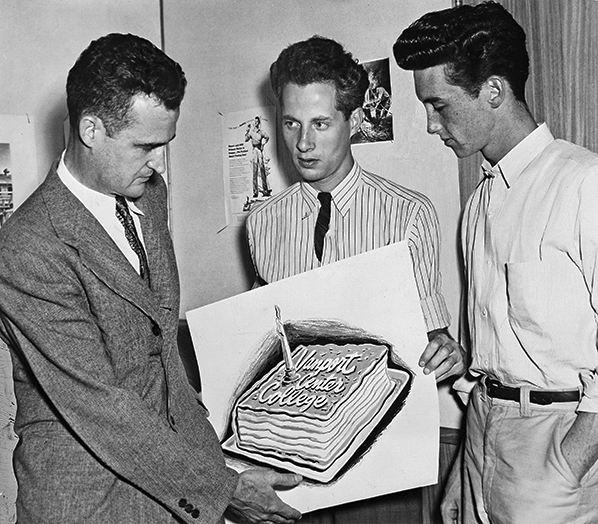

![]()

1948 Vanport flood victims resettled.

Courtesy Multnomah County Library -

![]()

Map of Vanport, by Maben Manly.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 94480

-

![Robert Oga moved from the Minidoka Internment camp in Idaho to Vanport in 1945.]()

Robert Oga's shipping crate, 1945.

Robert Oga moved from the Minidoka Internment camp in Idaho to Vanport in 1945. Oregon Historical Society Museum Collection, 2006-69

Related Entries

-

![Ancer L. Haggerty (1944–)]()

Ancer L. Haggerty (1944–)

Ancer L. Haggerty was the first African American to become a partner in…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Housing Authority of Portland]()

Housing Authority of Portland

The Housing Authority of Portland was created in 1941 in response to th…

-

![Kaiser Shipyards]()

Kaiser Shipyards

During World War II, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser established three sh…

-

![Stephen E. Epler (1909-1997)]()

Stephen E. Epler (1909-1997)

Stephen E. Epler, the founder of the Vanport Extension Center&mdas…

-

!["Sweet Baby" James Benton (1930-2016)]()

"Sweet Baby" James Benton (1930-2016)

James Benton has been a singer of jazz, blues, and R&B; during two dist…

-

![Vanport Extension Center]()

Vanport Extension Center

The Vanport Extension Center grew from a converted shopping mall and re…

-

![Vern Rutsala (1934–2014)]()

Vern Rutsala (1934–2014)

Vern Rutsala’s poetry is an expression of Oregon and the West. His peop…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Hayden, Dolores. Redesigning the American Dream. New York: W.W. Norton, 1984.

Kilbourn, Charlotte, and Margaret Lantis. "Elements of Tenant Instability in a War Housing Project." American Sociological Review 11 (February 1946).

Maben, Manly. Vanport. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1987.

McElderry, Stuart. "Vanport Conspiracy Rumors and Social Relations in Portland, 1940-1950." Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 99, no.2 (Summer 1998): 134-163.

Oregon Historical Society. Digital Collections. Vanport Photographs.

Skovgaard, Dale. "Memories of the 1948 Vanport Flood." Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 108, no.1 (Spring 2007): 88-106.