During the war-hot summer of 1970, thousands of young people began streaming toward Clackamas County's Milo McIver State Park to attend Vortex I, a state-sponsored rock-music festival. Ed Westerdahl, chief of staff to Governor Tom McCall, had selected the 847-acre site, some thirty miles southeast of Portland. The park provided all the advantages that Westerdahl sought—a rural setting, proximity to Portland, and easy driving distance from Interstate 5. The festival was strategically planned to attract young anti-Vietnam war protestors who otherwise might descend on Portland to disrupt the American Legion's annual convention, which would begin on Sunday, August 30.

Even before Vortex I began, 2,000 people had entered the park; and by the time the festival officially opened on Friday, August 28, the population of McIver State Park had reached 5,000. At the close of the concert's second day, some 35,000 young people were jostling for space in the hot afternoon sun. Many of those who attended the festival were curious people from surrounding communities who came to witness the expected—young people smoking marijuana, many of them naked and frolicking in the Clackamas River to keep cool.

Vortex I was a rousing success. Television, radio, and the print media reported rural county roads clogged with vehicles, many of them sporting bright, psychedelic colors. To provide parking space, the state had leased several fields in the vicinity of McIver State Park. Because of the large number of aircraft circling above the park, Portland's Federal Aviation Administration office warned that overhead airspace was unsafe.

The origins of the festival—now shrouded in fading memory and photographs—can be found in the Oregonian's announcement in late May that Portland, still healing from protests against the Vietnam War on Portland's South Park Blocks, would host the American Legion convention in September. To complicate things, the paper reported that President Richard Nixon, a special object of war protestors' loathing, would address the convention. In late June, matters became more worrisome when the FBI informed Governor McCall that 50,000 anti-war radicals—the Peoples' Army Jamboree, an impromptu anti-war group—were organizing to disrupt the Legion convention. Although recent evidence shows that the FBI memo greatly exaggerated the situation, McCall's staff and the governor saw no reason to question the report, especially given the National Guard's killing of four students at Kent State University earlier that spring.

With mixed emotions about recent anti-war riots at Portland State University and the Park Blocks, some activists were eager to avoid further violence. Hindsight also reveals that FBI evidence was based on rumor and deliberately misleading informants. In response to a journalist's question to one of the Jamboree's leaders about the FBI estimate of 50,000 protestors, Peter Fornara replied: "We heard that the Legion expected to bring twenty-five thousand people to Portland, so we just doubled the number, made it up out of thin air. The number meant nothing. It was just talk." McCall biographer Brent Walth concluded: "What truly was at work in the summer of 1970 was not fact but fear."

The governor's office became even more alarmed when newspapers reported that Jamboree leaders were applying to use nearby Washington Park as a base of operations. In the midst of swirling rumors, threat, and counter-threat, a small group of activists calling themselves The Family suggested the idea of a free alternative, a Woodstock-like rock concert that would help defuse the situation. One activist called it "a peaceful coming together," a vortex for peace. When city officials refused to listen to the proposal, four members of The Family traveled to Salem, where they met with McCall staffer Ed Westerdahl, who was frantically trying to resolve the potential for violence in downtown Portland. "An odd scene," writes Walth, "Westerdahl in a crewcut and suit," and his long-haired visitors making their case. Westerdahl liked the idea and thought that McIver State Park was suitable for a rock festival. He then persuaded Governor McCall, who was in the midst of a reelection campaign, to back the plan.

Westerdahl determined that the state should fully sponsor Vortex and that law enforcement officers would keep a low profile, turning a blind eye to any Woodstock-like behavior, including nudity and marijuana use. When Westerdahl and his counter-cultural confederates announced plans for Vortex on August 6, reporters were in disbelief, with conservative Portland City Commissioner Frank Ivancie the most vocal critic. While the governor ordered select Oregon National Guard units to undergo riot training, downtown businesses prepared for the worst.

When the thousands of rock-festival fans began to leave McIver State Park in droves on Sunday, most of them simply returned to their homes. In the end, President Nixon canceled his Portland visit, and only two small marches took place in the city, involving some 1,000 protestors. Other than the shouting of anti-war slogans, Portland remained quiet. With the perspective of time, it is clear that FBI misinformation led to exaggerated predictions, overreaction, and paranoia. and whether Vortex saved Portland from chaos is the subject of ongoing debate. Memory plays still other tricks with those who attended the event. A standard bit of humor shared among those who were in attendance is that no one can recall the names of the musical performers.

-

![]()

Members of The Gangsters performing on an elevated stage at Milo McIver State Park during the Vortex I Music Festival.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003056

-

![]()

Revelers at Vortex I .

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003058

-

![]()

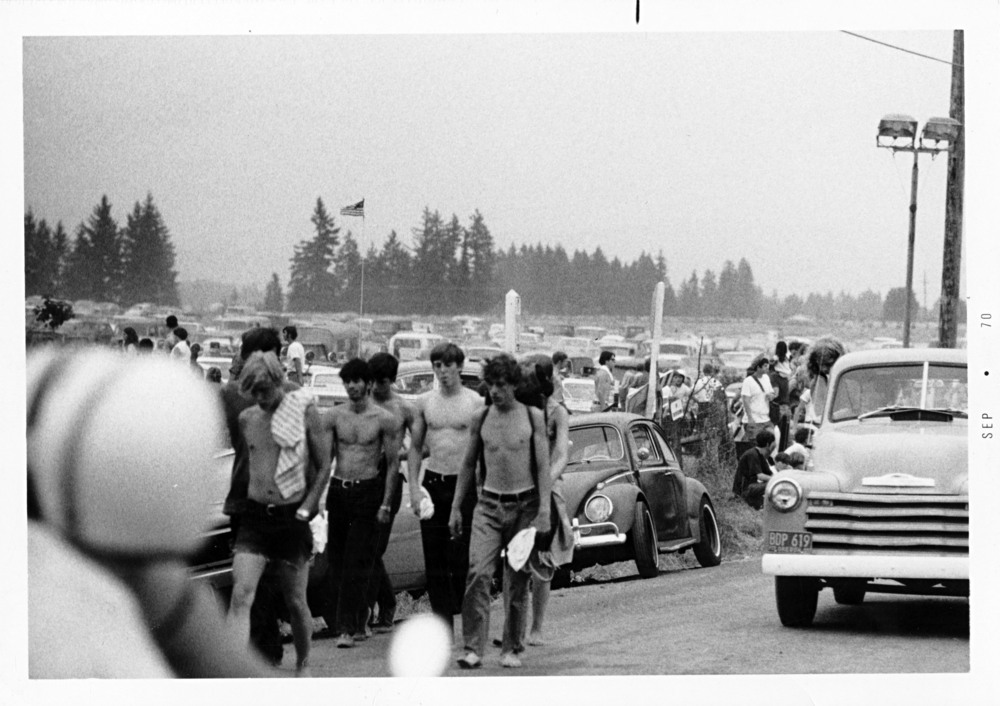

People entering McIver State Park to attend Vortex I.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 103979

Portland City Council meeting regarding use of Washington Park for Vietnam War protest, 1970

/media/uploads/City_Council_meeting_Vortex.mp4

Related Entries

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Love, Matt. The Far Out Story of Vortex I. Nestucca, Ore.: Nestucca Spit Press, 2004.

Walth, Brent. Fire at Eden's Gate: Tom McCall and the Oregon Story. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1995.