"The most devastating work stoppage in Oregon's history" lasted 82 days, paralyzed commerce, and laid off 50,000 Oregonians. It also established one of the nation's strongest unions on the West Coast.

In 2008, ninety-five-year old retired longshoreman Marvin Ricks was the last surviving Portland veteran of the great West Coast waterfront strike of 1934. When he needs a taxi, he wants a Broadway. He remembers that Broadway cabbies delivered sandwiches to him and his comrades on the picket lines.

Those sandwiches were lovingly prepared by Margie, Kay, Florence, Helen, and "Smiles"—women of the Villa Rooms on NW Third Avenue off Burnside, who may also have offered other services on credit for the duration. The strikers also got crucial support from farmers who brought milk, fishermen who delivered clams, hunters who contributed deer for the strike soup kitchen, and the college students who signed pledges not to scab. Despite widespread unemployment, the Oregon Workers Alliance promised their 30,000 members they would stand "five men deep along the waterfront and there would be no scabbing." Even some sympathetic Portland police officers passed on intelligence to the strikers.

There are no known survivors among the opponents—or targets—of the strike. As members of Oregon's better known families, including those linked to its early history, they were just as determined to break the strike as Ricks and his union members were to win it. They considered the strike a clear and present danger to the state and formed a Citizens Emergency Committee to open the port. The group was led by a host of luminaries, including the Failing estate's Henry Cabell, Henry L. Corbett, lumberman Aubrey Watzek, Amedee Smith, E.G. Sammons, attorney Robert Sabin, Frank Warren, E.B. MacNaughton, Harold Wendel, Henry Wessinger, Harold Stanford, and Gen. Ulysses U.S. Grant "Rock of the Marne" Alexander —all supported by the staff of the Portland Chamber of Commerce. If the local press showed more sympathy for them than to the strikers, the presence on the committee of Simeon Winch, Don Sterling, and Philip Jackson of the Oregon Journal, Paul Kelty, Palmer Hoyt and O.L. Price of The Oregonian, and Tom Shea of the News-Telegram may offer an explanation.

Oregon Governor Julius Meier pleaded unsuccessfully with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to send federal troops to stop the strike, because, he concluded, "we are now in a state of armed hostilities." The Portland Chamber of Commerce received a warning from the U.S. Army that "Portland is the worse spot in which to release troops at this time because if there is a revolution in the making, such action would precipitate it."

In that atmosphere, the Citizens Committee voted to hire more than 1,000 vigilantes, organized into a semi-military organization called the Citizens Emergency League. Declaring that "we must end the strike with peaceful means, if possible, but if necessary by other means," they accepted that deployment could "doubtless lead to bloodshed and perhaps loss of life."

And there was bloodshed and loss of life. Hired strikebreakers were housed on the Admiral Evans, which the strikers attacked and cut loose to drift into the Broadway Bridge. Police, escorting a train to Terminal Four in St. Johns, fired on the strikers, wounding four of them in what became known as "Bloody Wednesday." The strikers' "navy" plied the waterfront armed with slingshots to discourage strikebreakers. Vigilantes fired on a car carrying New York Senator Robert Wagner, sent by President Roosevelt to mediate the strike. It was not until the strike ended in victory for the longshoremen that the first death was recorded. James Connor, a student, was killed by shots fired when union men demonstrated against strike breakers at Alberta Hall. Marvin Ricks was among the twenty-nine longshoremen falsely arrested for murder in that incident.

The longshoremen's solidarity, community support, and militancy won them coast-wide union recognition, a joint hiring hall, and substantial wage and hour improvements. The Portland local joined the post-strike movement to reject their corrupt AFL union and to join Harry Bridges's International Longshore & Warehouse Union (ILWU). Oregon ILWU locals now include Portland 8 and 40, North Bend 12, Astoria 50, Powell's 5, as well as the Columbia River Pensioners Association, which stand on the foundation of the 1934 strike as rare survivors of militant unionism.

-

![]()

The Great Waterfront Strike of 1934.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library bb002207

-

![This coin indicates membership in the Citizens' Emergency League (CEL), a civilian paramilitary organization formed in 1934 to aid law enforcement in emergency response, namely in suppressing the 1934 Maritime Strike.]()

Citizen's Emergency League Fraternal medal, 1934.

This coin indicates membership in the Citizens' Emergency League (CEL), a civilian paramilitary organization formed in 1934 to aid law enforcement in emergency response, namely in suppressing the 1934 Maritime Strike. Oregon Historical Society Museum Collection, 72-78.33

Related Entries

-

![Francis J. Murnane (1914–1968)]()

Francis J. Murnane (1914–1968)

Francis J. Murnane was a longshoreman, labor leader, writer, and preser…

-

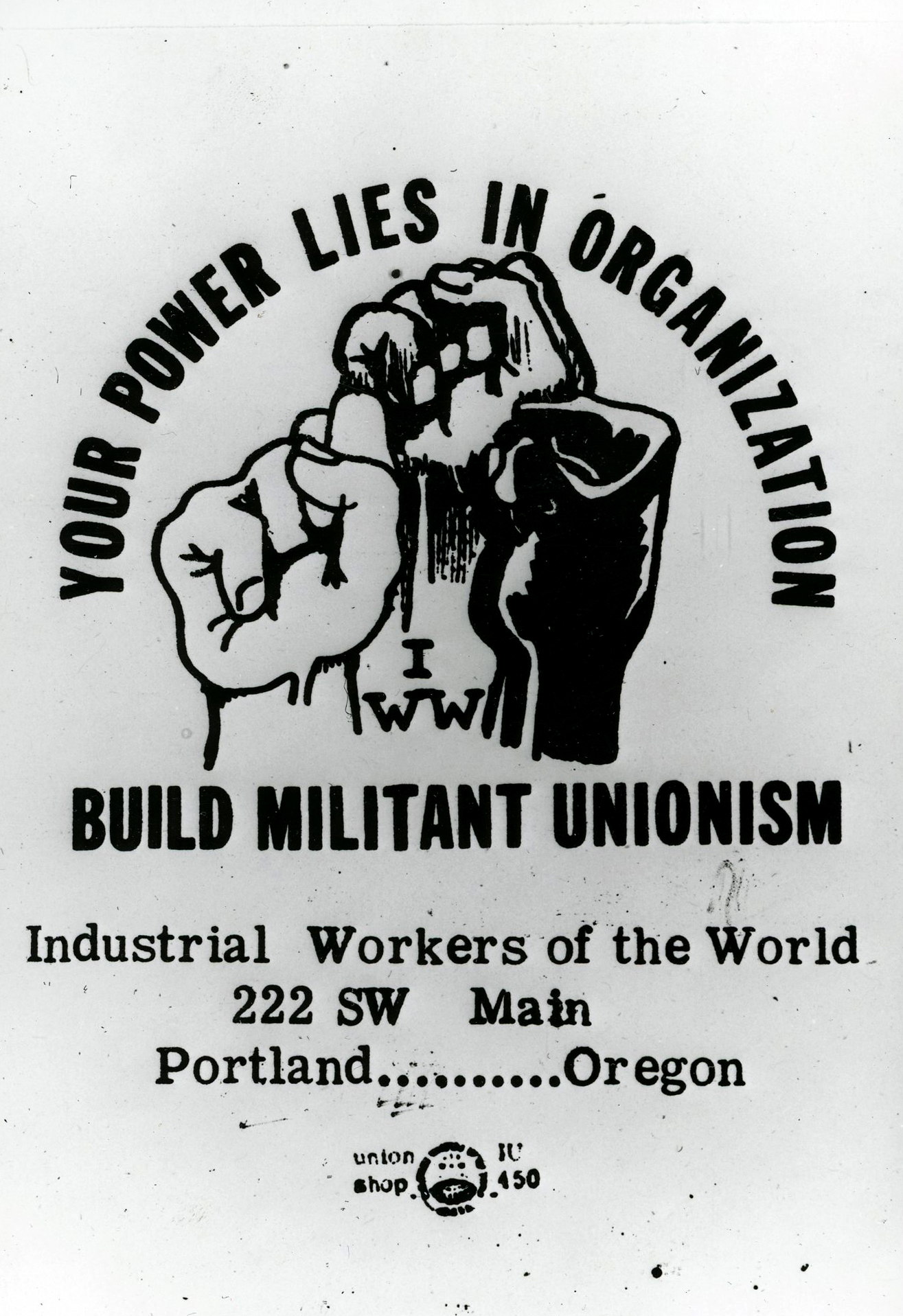

![Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)]()

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), founded in 190…

-

![Irvin Goodman (1896–1958)]()

Irvin Goodman (1896–1958)

Before there was Gideon v. Wainwright or an Oregon public defender, the…

-

![Julia Ruuttila (1907-1991)]()

Julia Ruuttila (1907-1991)

Julia Ruuttila was a labor and investigative journalist, a poet and fic…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bigelow, William, and Norman Diamond. “Agitate, Educate, Organize: Portland, 1934." Oregon Historical Quarterly 89:1 (Spring 1988), 5-29.

Buchanan, Roger B. Dock Strike: History of the 1934 Waterfront Strike in Portland, Oregon. Everett, Wash.: Working Press, 1975.

MacColl, E. Kimbark. The Growth of the City: Power and Politics in Portland, Oregon 1915 to 1950. Portland, Ore.: Georgian Press, 1979, pp. 467-486.

Munk, Michael. "Portland's 'Silk Stocking Mob': The Citizens Emergency League in the 1934 Maritime Strike." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 91:3 (Summer 2000), 150-161.