During the summer of 1905, while visitors enjoyed the amusements of the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, one of the most sensational trials in Oregon's history was taking place at the Pioneer Courthouse in downtown Portland. The defendant was John H. Mitchell, then serving his fourth term in the U.S. Senate and arguably the most powerful politician in the state. His conviction in federal district court on July 3 marked the climax of what became known as the Oregon Land Fraud Trials.

The trials had their genesis in two letters. The first, sent by a Catholic priest, alerted Interior Secretary Ethan A. Hitchcock to frauds in Tillamook. Hitchcock assigned Inspector Alfred A. Greene to look into the matter, and Greene's investigation led him to Stephen A.D. Puter. A second letter from an Arizona lawyer alleged a fraud conspiracy by land speculators Frederick A. Hyde and John A. Benson in California and Arizona. When Binger Hermann, commissioner of the General Land Office, took steps to cover up the Hyde and Benson affair, Hitchcock demanded his resignation and brought in Secret Service agent William J. Burns to investigate.

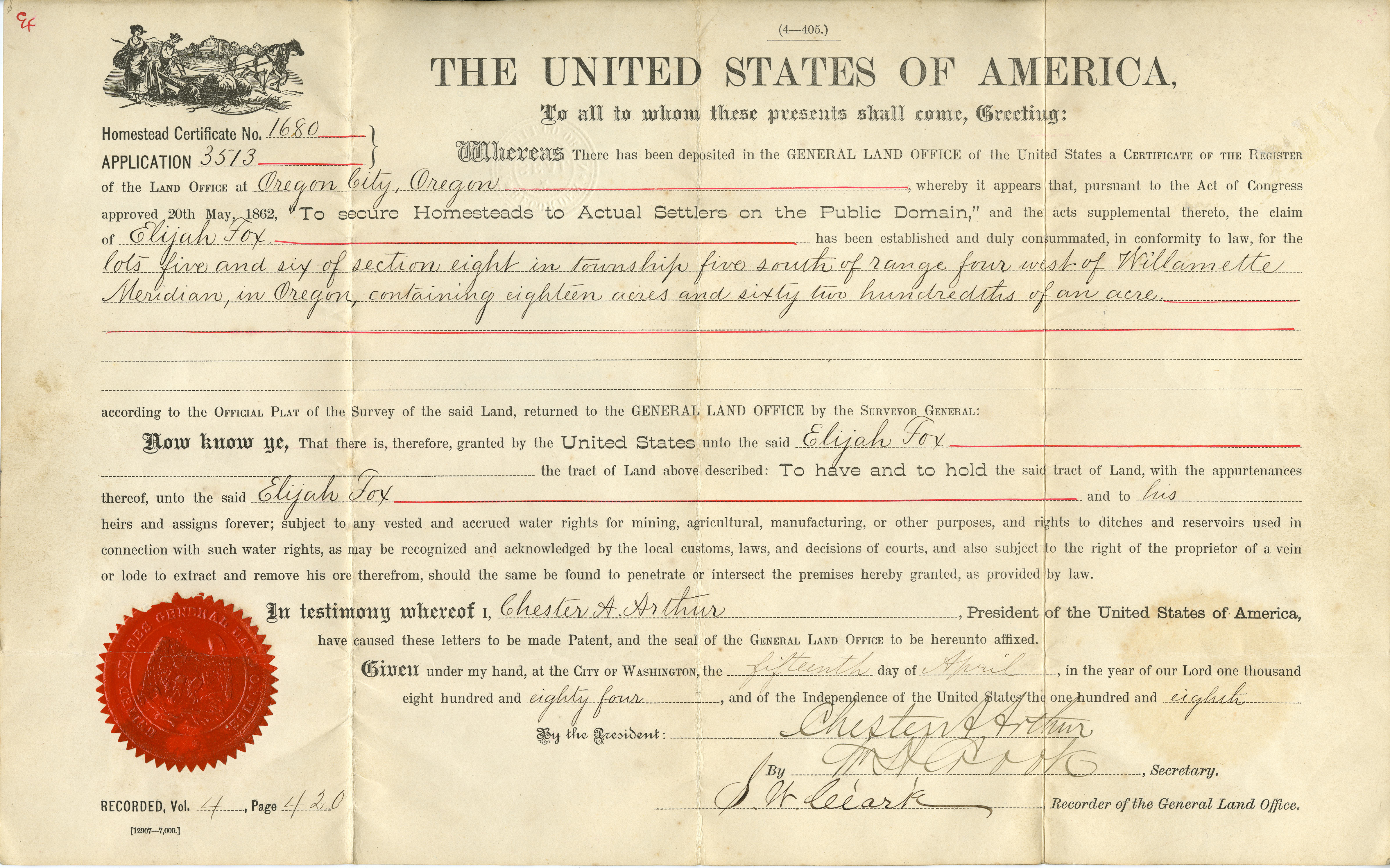

The frauds in Oregon and California centered on the homestead laws, which provided for the sale of public land to proven settlers. According to the evidence gathered by Greene and Burns, speculators filed fraudulent claims and bribed General Land Office officials to approve them. In some cases, the names of the homesteaders were entirely fictitious. Once the patents had been approved, they were sold to lumber and livestock companies for a profit. By this means, great tracts of valuable timber and grazing land were stolen from the American public.

In 1903, grand juries in Washington, D.C., and Portland indicted Hyde, Benson, Puter, and their co-conspirators. Attorney General Philander Knox appointed San Francisco lawyer Francis J. Heney to lead the prosecutions.

Following Puter's conviction in 1904, Heney and Burns persuaded him to cooperate in their investigation. Puter implicated several prominent officials in his testimony and helped elicit confessions from conspirators to substantiate his allegations. By the time the Portland grand jury concluded its term in 1905, it had indicted nearly one hundred people, including Hermann, Mitchell, U.S. District Attorney John Hall, and Congressman John N. Williamson.

Mitchell's trial centered on a series of payments Frederick A. Kribs made to the senator. After both Mitchell's law partner and his private secretary testified against him, the jury returned a guilty verdict.

Heney next turned to Williamson, who was charged with conspiring to defraud the government out of several thousand acres of grazing land for his sheep ranch near Prineville. Two juries failed to reach unanimity, however, and it was only at the conclusion of a third trial in January 1906 that a jury finally convicted him. Williamson, like Mitchell, quickly filed an appeal.

Hall's indictment derived from the Butte Creek Land, Livestock, and Lumber Company's acquisition of land near Fossil. At the time he was vying for reappointment as district attorney, and he protected the company from prosecution in exchange for political support. A jury found him guilty in 1908.

The final trial was that of Binger Hermann, who was charged with manipulating the boundaries of a proposed forest reserve in the Blue Mountains to include lands owned by Franklin P. Mays, a former state senator and U.S. district attorney. The trial ended on February 14, 1910, with a hung jury, deadlocked by a single holdout.

The exposure and vigorous prosecution of land fraud and public corruption initially helped President Theodore Roosevelt advance his conservation agenda. In 1905, Congress amended the land laws and transferred control of the nation's forests from the General Land Office to the U.S. Forest Service. The Democratic Party in Oregon also benefited from the scandals, beginning with Harry Lane's election as Portland mayor in 1905.

In the long run, the legacy of the Oregon Land Fraud Trials was more ambiguous. Senator Charles W. Fulton passed an amendment to the 1907 Agriculture Appropriations bill that curtailed the president's authority to create new national forests. Oregon's Republican Party rebounded in 1909 with Joseph Simon's election as mayor of Portland. Mitchell died before his appeal could be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned Williamson's conviction. Hall and Mays were later pardoned by President William Howard Taft, which Roosevelt alleged was part of a deal to deny him the Republican nomination in 1912.

Nonetheless, the Oregon land fraud trials symbolized an epochal shift in Oregon. With Mitchell’s conviction, an echo of the Gilded Age drew to a close and the era of the Progressives began.

-

![Mitchell land fraud trial cartoon, Oregonian, 1905, by Harry Murphy]()

Mitchell trial, editorial cartoon, 1905.

Mitchell land fraud trial cartoon, Oregonian, 1905, by Harry Murphy Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

![Binger Hermann (1843-1926)]()

Binger Hermann (1843-1926)

Binger Hermann was a Roseburg attorney and politician who represented O…

-

![John Hipple Mitchell (1835-1905)]()

John Hipple Mitchell (1835-1905)

John Hipple Mitchell was a Portland lawyer and politician whose long ca…

-

![Stephen Puter (1857-1931)]()

Stephen Puter (1857-1931)

Stephen Puter was the self-described King of the Oregon Land Fraud Ring…

-

![U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946]()

U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946

With the acquisition of the Oregon Country in 1846, the United States w…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Messing, John. "Public Lands, Politics, and Progressives: The Oregon Land Fraud Trials, 1903-1910." Pacific Historical Review 35:1 (February 1966): 35-66.

Puter, Stephen A.D., and Horace Stevens. Looters of the Public Domain. Portland, OR: The Portland Printing House, 1908.