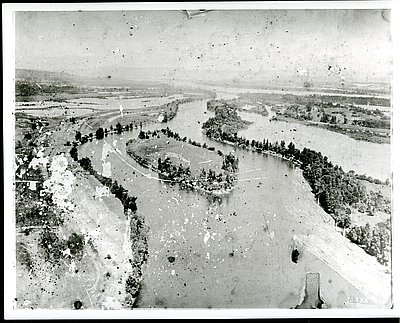

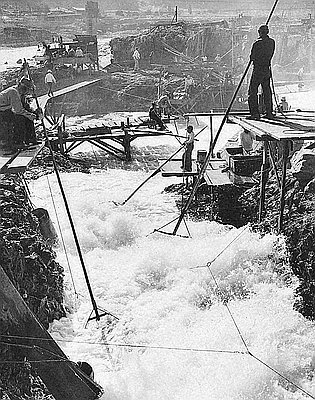

Dipnetters at Celilo Falls, a Native fishery and trading site on the Columbia River used for millennia. 1957. The U.S. Corps of Engineers inundated Celilo the year this picture was taken, a casualty of The Dalles Dam constructed downriver. OHS, CN 007237

An introduction

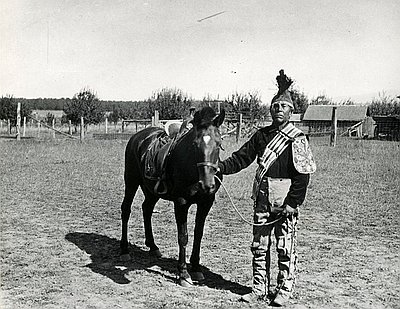

The history of the State of Oregon is short; the history of people in this place is much longer. A non-Native Oregonian can claim, at most, eight generations. Native Oregonians can claim hundreds. Early white settlers predicted that Native people would fade away and disappear from Oregon. They were wrong.

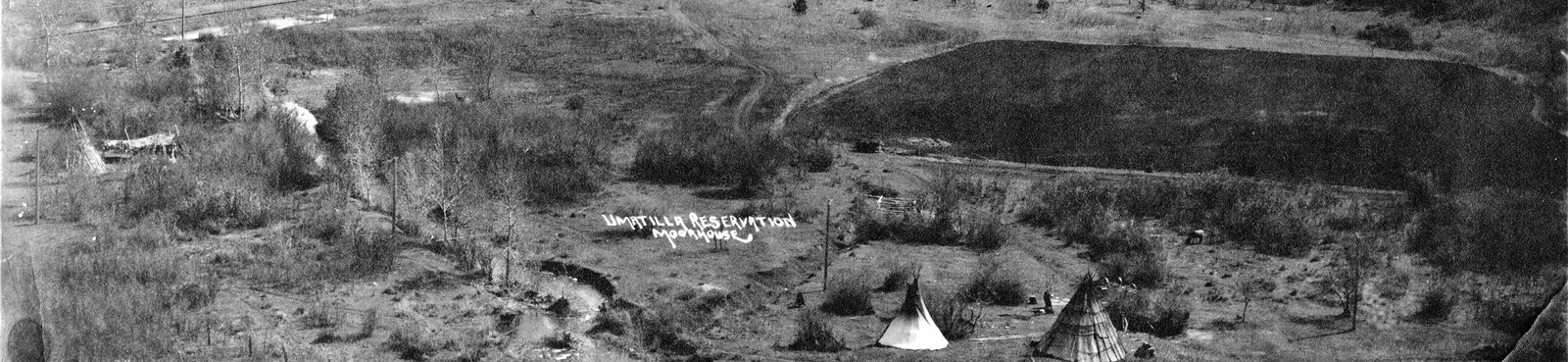

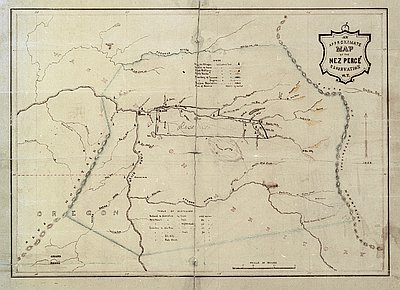

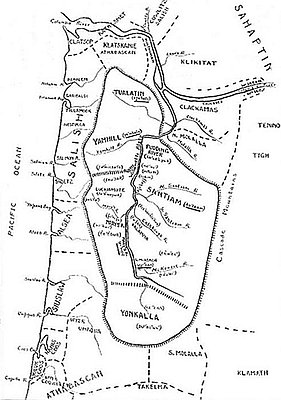

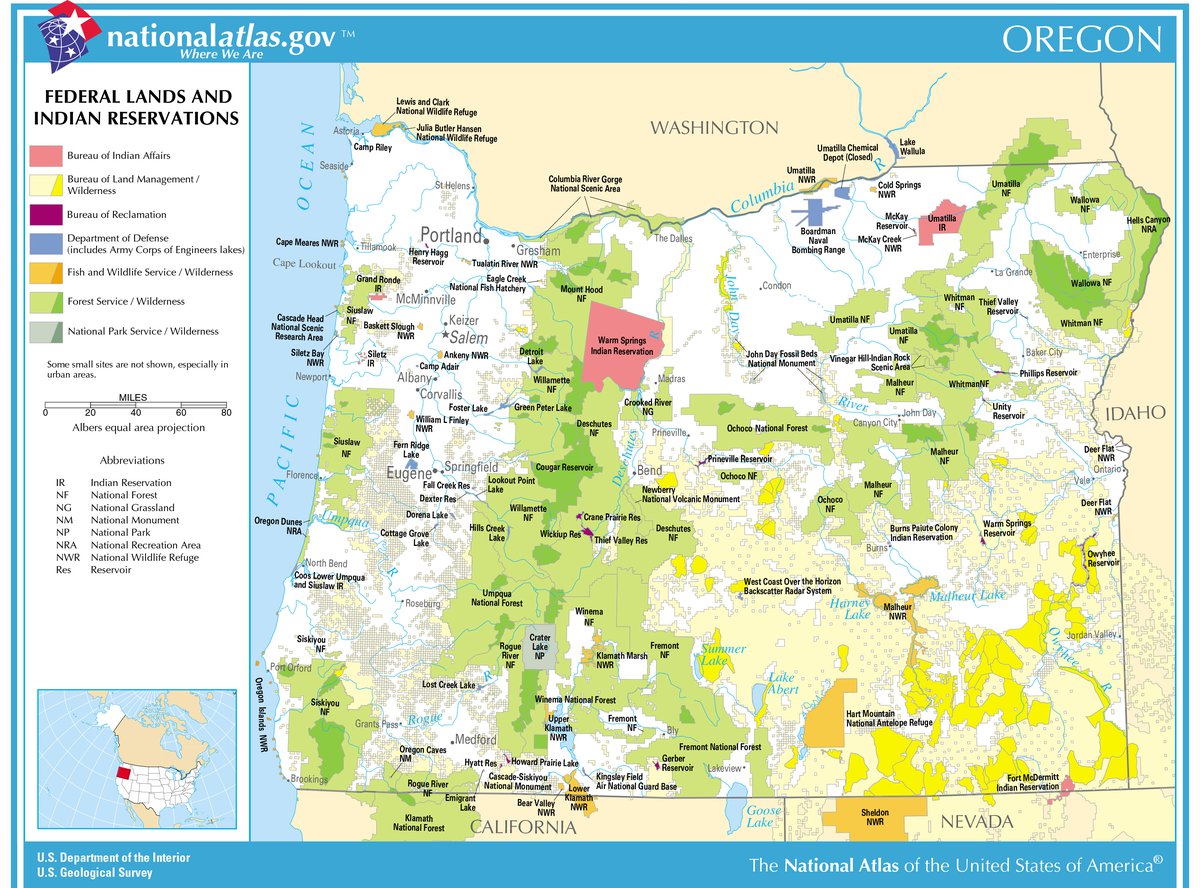

The United States government recognizes more than seventy tribes on nine reservations in the State of Oregon, a result of treaties ratified by Congress, executive actions taken by U.S. presidents, and adjudication by federal courts. Dozens of bands and tribes were confederated onto reservations, some of them far from traditional homelands.

For many years, the U.S. government cut away at reservation boundaries. Then, in 1954, Congress targeted Oregon tribes with Public Laws 587 and 588, known as the Termination Acts, ending the trust relationships between the federal government and Native nations. Members of sixty-three Oregon tribes and bands at three reservations and other Native communities endured the deleterious effects of Termination, including the loss of their sovereignty, their land, and their community.

Beginning in 1972, some Oregon tribes gained back their sovereignty and their land trust rights with Restoration, legislation that was the result of years of advocacy. Since then, many tribes have had land returned by congressional acts and have purchased or negotiated for the land they lost, an effort that continues to this day. Some tribes continue to seek federal recognition. The experiences of Indigenous people in Oregon over generations, including those who were removed from the state, are essential to understanding the history of Oregon.

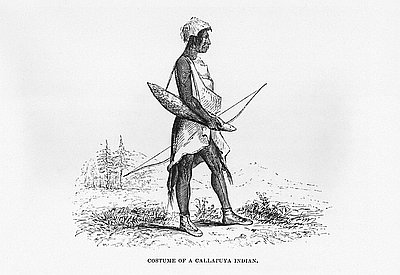

Most of the early written record of Native people in what became Oregon is from non-Natives who largely had limited interactions with Indigenous people and perceived them as culturally inferior. The result of this biased perspective generally obviated the histories that Native people have preserved for thousands of years through cultural practices such as oral traditions, placenaming, art, and ceremony. Today, Native historians and other scholars are generally committed to narrating a history that is honest, accurate, and revealing.

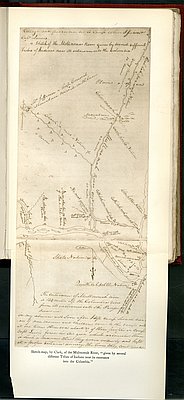

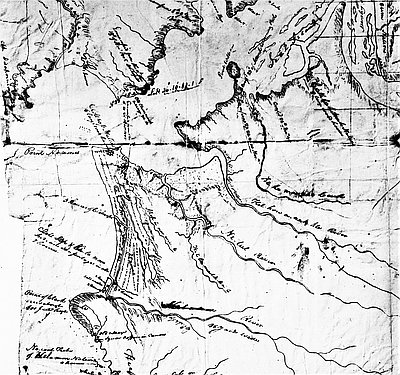

Map of Indian Reservations in Oregon

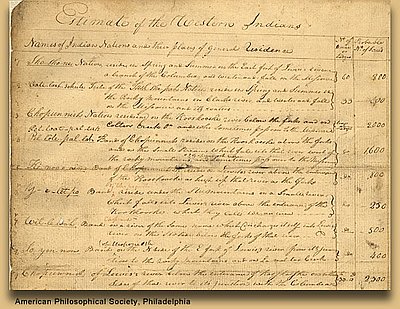

The first treaty between Indigenous people and the United States government was in 1778. The agreement, in form and purpose, resembled those the U.S. made with all sovereign nations--pacts agreed on by both parties to determine land cessions and economic relations between the United States and Indian Nations. By 1832, Congress had redefined tribal nations as domestic dependent nations (that is, part of the United States) and dependent on the federal government. The language and intent of subsequent treaties changed, based on America's assumed control over Indian Nations and its expressed purpose to occupy Native homelands. That occupation was contingent on the removal of Indians by any means necessary, which often led to violent, inhumane assaults on Native people.

The treaties signed in Oregon, beginning in the 1840s, were of this kind. In negotiations, federal agents and tribal headmen both agreed to treaty stipulations. Federal agents often acted with urgency, warning Indian negotiators to agree quickly or risk white incursions and violence. The reservations established by treaty, whose boundaries were heavily determined by the settlement and demands of whites, were confederated, which meant that several tribes were treaty signatories. Some reservations were not created through treaties but by presidential executive order or federal adjudicated procedures. The federal government now recognizes nine tribal governments in Oregon. Their reservations are managed and governed by each tribal Nation, and their lands are held in trust by the U.S. government.

Oregon History 101 (1)

In cooperation with McMenamins Pubs and regional scholars, The OE produced in 2014 a public history series, Oregon History 101, designed to provide an introduction to the history of Oregon. The first two programs outline the long history of Native people in the region and the effects of non-Native exploration and resource extraction.

"Two Hundred Years of Changes to Native Peoples of Western Oregon."

Presented by Dr. David Lewis (Takelma, Chinook, Molalla, Santiam, Kalapuya)

Oregon History 101 (2)

"A Century by Sea and Land: Explorers and Traders in Oregon Country, 1741-1850."

Presented by Dr. William Lang