Until he arrived in Hood River in 1942, William Sherman Burgoyne had never known any Japanese Americans, but he became an unwitting target when he came to their defense.

The descendant of a British general who had been defeated by American troops at Saratoga, Burgoyne was born in Stevensville, Montana, on October 24, 1901. He moved to Oregon in 1928. After attending four higher education institutions—Montana State College, Oregon State College, Kimball School of Theology, and Willamette University—the tall, burly Methodist minister served churches in McFarland, LaGrande, Turner, Cresswell, Sheridan, Laurelwood, and Marshfield, Oregon.

When Burgoyne and his wife Doris arrived in Hood River, local Japanese Americans had already been removed to government concentration camps and had sold or leased their farms to valley residents. In November 1944, amid an intense anti-Japanese campaign that discouraged Japanese Americans from returning after the war, Hood River’s American Legion Post removed the names of sixteen Japanese Americans from a community memorial board that listed local residents who served in the Armed Forces. The men, the Legion post claimed, were dual citizens of Japan and the United States and, therefore, not welcome.

In a letter to the Hood River News, Burgoyne criticized the action, claiming that "every person in Hood River County . . . is disgraced." He urged the town to replace the names. The first in a series of six large newspaper ads by former Chamber of Commerce manager Kent Shoemaker was "an open letter to W. Sherman Burgoyne." It began: "So Sorry Please, Japs Are Not Wanted in Hood River." The minister and his wife remained steadfast, even when Doris’s brother fell victim to a Japanese sniper on Guadalcanal.

Burgoyne co-founded the League for Liberty and Justice, aimed at thwarting propaganda and defending Japanese Americans in the Hood River Valley. Members of the league offered to shop for local Japanese Americans or drive produce trucks when workers declined their fruit, and the league urged chain stores to accept Japanese business.

Speaking out took its toll on Burgoyne. He was dubbed a "Jap Lover" and was frozen out of membership in local civic clubs. He could find no buyer for his ten-acre ranch. Membership at his church declined, and the church reassigned him to tiny Shedd, Oregon, before two district superintendents for the Methodist Church in Washington transferred him to Spokane, where he served a small congregation.

In 1947, Burgoyne gained national recognition for his advocacy of Japanese Americans. He received the Thomas Jefferson Award for advancing democracy and was honored by the Council Against Intolerance in America, along with Eleanor Roosevelt, former Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall, and Frank Sinatra. Burgoyne also served for many years on the executive board of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

-

![]()

Oregonian article reporting Sherman Burgoyne receiving Thomas Jefferson award, Feb. 11, 1947.

Courtesy Portland Oregonian

-

![]()

Japanese being evacuated from Hood River, 1942.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Extension Bulletin Illustrations Photo File, P020:0787

Related Entries

-

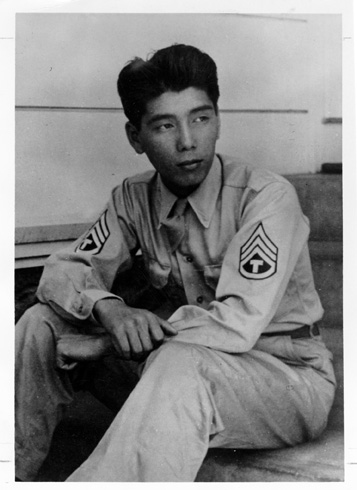

![Frank Hachiya (1920-1945)]()

Frank Hachiya (1920-1945)

The name Frank T. Hachiya will forever be linked to Oregon’s Hood River…

-

![Hood River (city)]()

Hood River (city)

Situated in the Columbia River Gorge about sixty miles east of Portland…

-

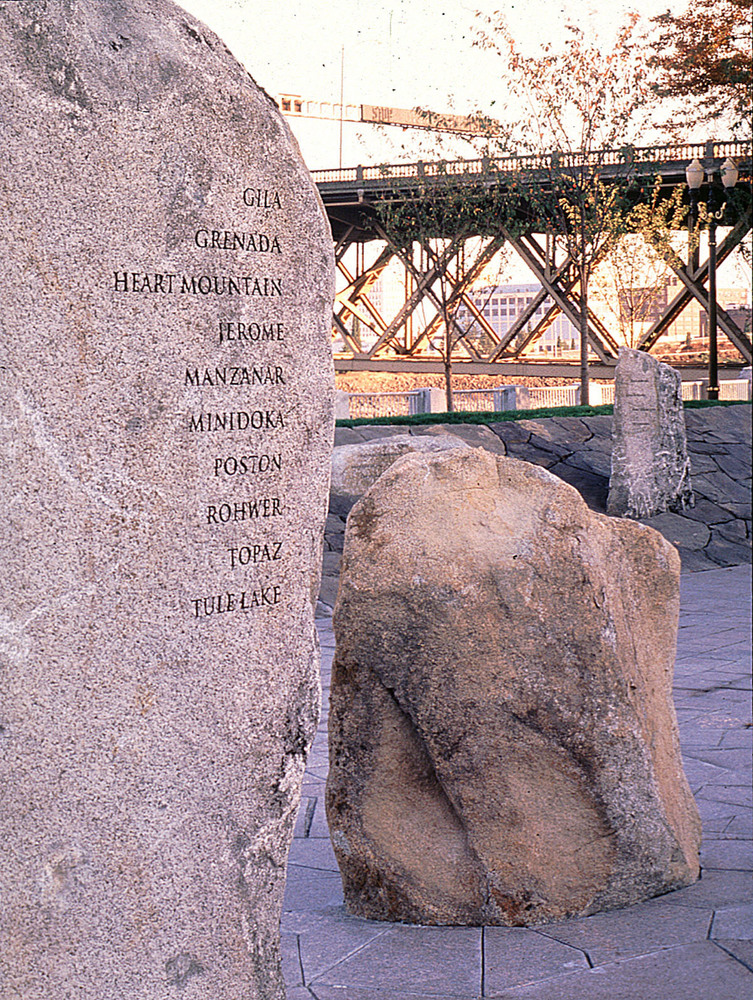

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

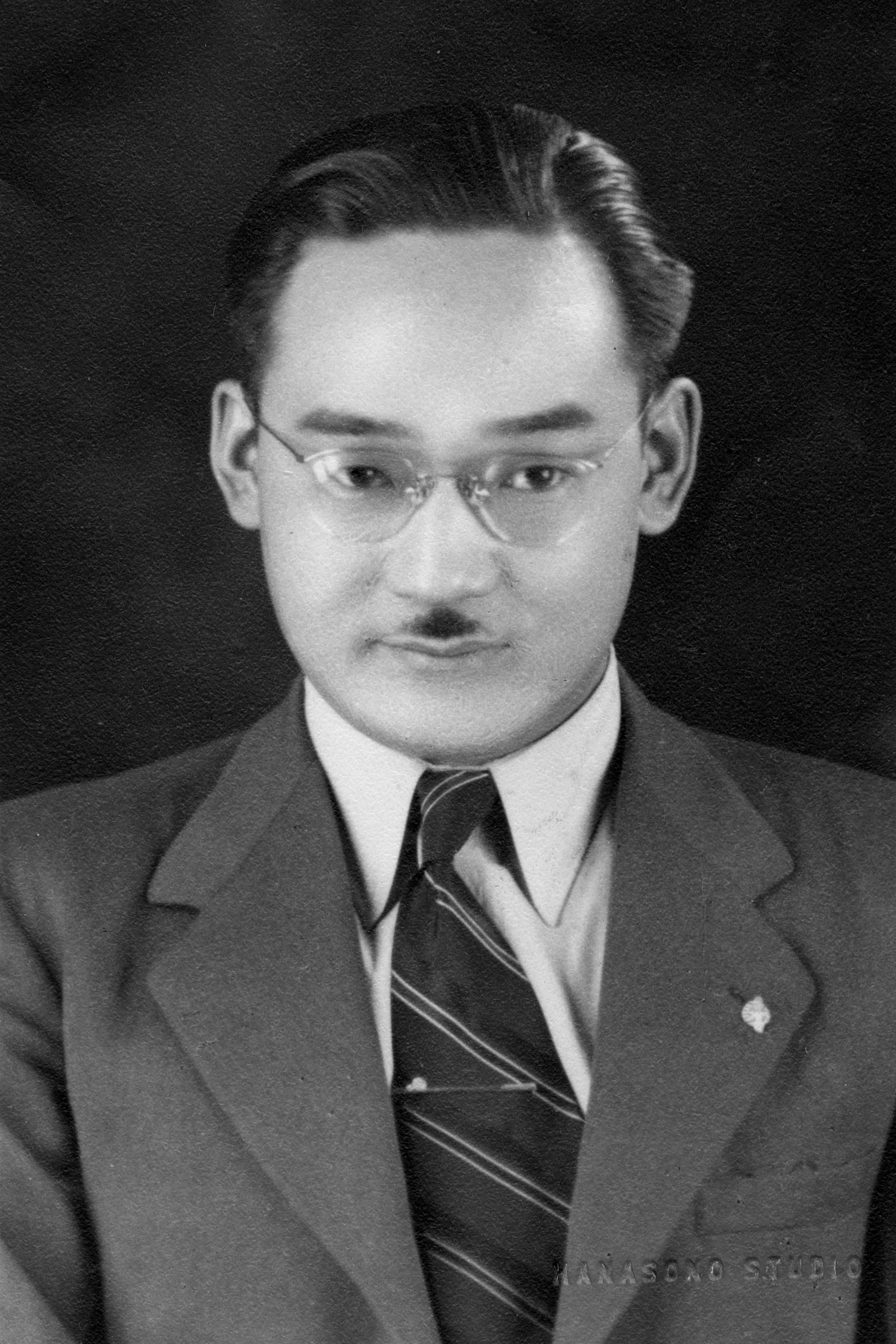

![Minoru Yasui (1916–1986)]()

Minoru Yasui (1916–1986)

Minoru Yasui was born in Hood River on October 16, 1916, the third son …

-

![Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984)]()

Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984)

A humble wife, mother, and public servant in Hood River, Shizue Iwatsuk…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Kitasako, John. “Methodist Minister Led Fight For Freedom in Hood River." Pacific Citizen, May 3, 1947.

Tamura, Linda. The Hood River Issei. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1993.