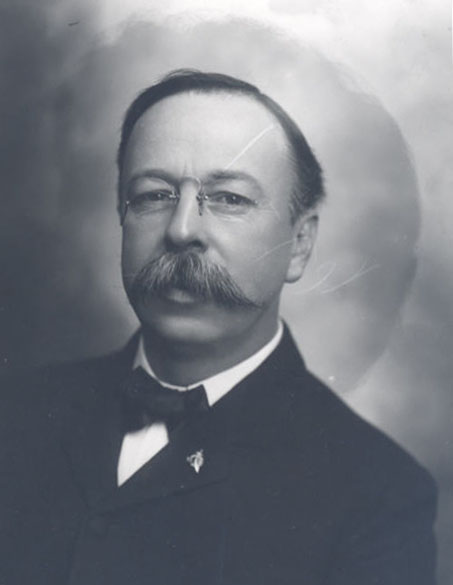

Largely because of his reputation as a scrupulously honest attorney general, Democrat George Earle Chamberlain was elected Oregon governor in 1902 with a slim majority of 246 votes. Chamberlain quickly established himself as a strong, energetic governor and a dedicated reformer who defended the state’s newly adopted initiative and referendum, known as the Oregon System, from those seeking to weaken the role of voters at the ballot box. In an age of Oregon reformers—such as Oswald D. West and Harry Lane—Chamberlain’s reform record stood out during his two terms as governor and his years in the U.S. Senate.

Born on a plantation near Natchez, Mississippi, in 1854, Chamberlain attended local schools and Washington and Lee University in Virginia, graduating with a law degree in 1876. He married Sallie Newman Welch in 1879, and the couple had seven children. Chamberlain immigrated to Oregon the same year, taught school near Albany, was admitted to the bar in 1879, and began practicing law. Voters elected him to Oregon’s House of Representatives in 1880 and again in 1882.

Appointed as Oregon’s first attorney general in 1891 and elected to a full term the following year, he served until 1895, establishing a reputation as a person of integrity, according to historian Dorothy Johansen.

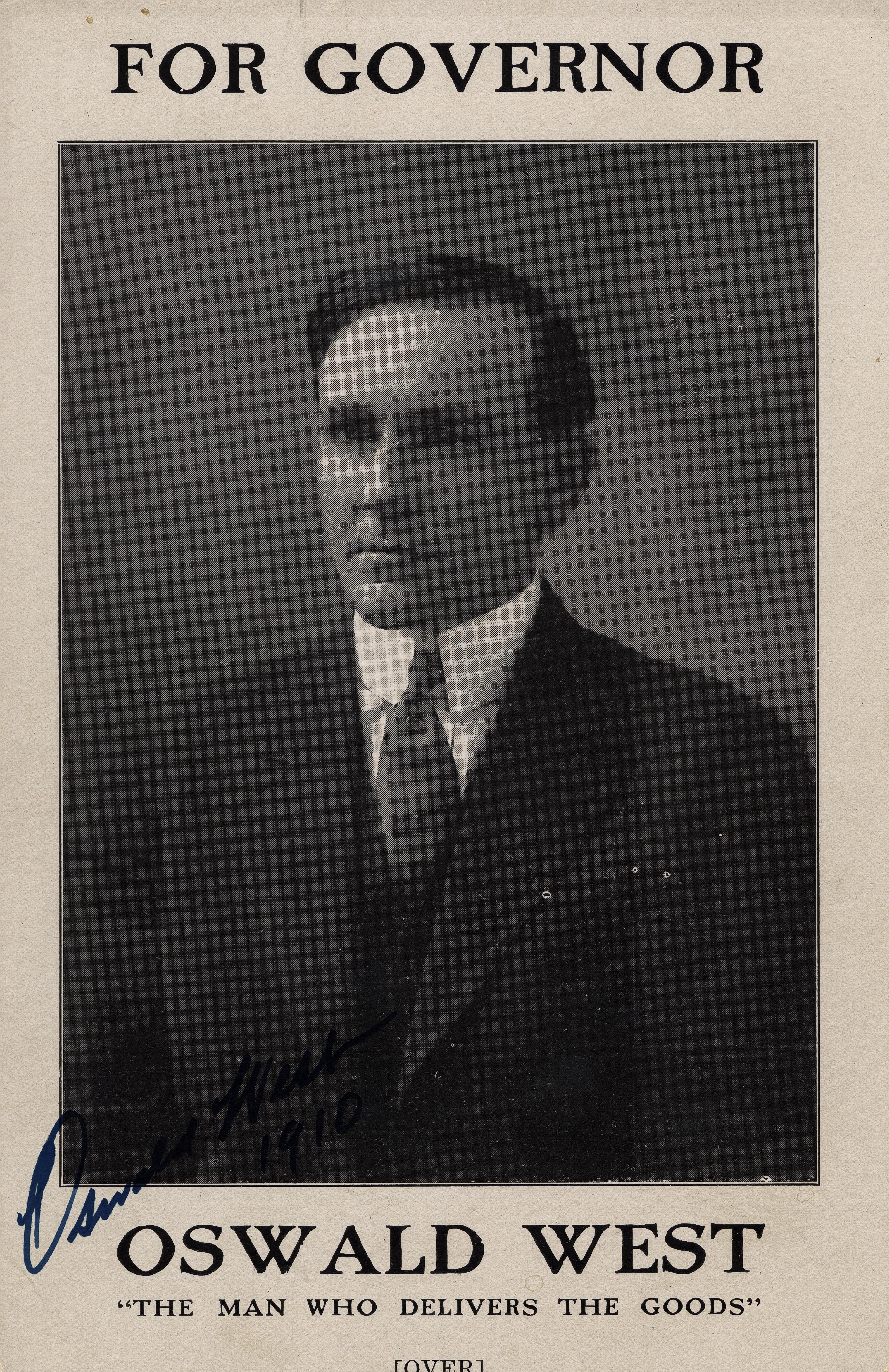

Once in the governor’s office, Chamberlain proved to be a progressive reformer in the mold of President Theodore Roosevelt, enforcing restrictions on the salmon industry, gaining public support for reclamation and hydropower projects, passing a graduated income tax, and expanding the national forest system. Most notably, Chamberlain appointed Oswald West as the state’s land agent to investigate fraudulent practices in the sale of Oregon’s school lands. West’s report in 1904 led to the Oregon land fraud trials of 1905.

Chamberlain’s legislative initiatives were wide-ranging, including reforming prisons (minimum sentences and parole programs), establishing state railway and library commissions, setting up a labor bureau, and supporting a child labor law. A fiscal conservative, he vetoed legislative bills that he considered extravagant, poorly drafted, or unrestrained raids on Oregon’s treasury. Although the legislature overrode some of his vetoes, Chamberlain chose to use the power of the governor’s office rather than leave what he considered faulty legislative bills to public referenda.

His ascension to the U.S. Senate was linked to a People’s Power League initiative in 1908. Because a majority of the Republican-dominated legislature had signed the initiative’s Statement No. 1—which directed legislators to support the winning candidate for U.S. senator in the primary election, the “people’s choice”—they reluctantly elected Chamberlain to the Senate. When he ran for a second term six years later, voters easily reelected him under the proviso of the Seventeenth Amendment (1913) that provided for the direct election of senators.

While in the Senate, Chamberlain supported progressive conservation measures, including the policies of the U.S. Forest Service. Like Charles McNary, who joined him in the Senate in 1917, he advocated cooperation between state and federal agencies and private interests to promote the common welfare and to make government more efficient and responsive. While these policies seemed farsighted at the time, they created opportunity for private interests to shape federal natural resource policies.

Chamberlain was chief sponsor of the Chamberlain-Ferris Act of 1916, the organic law for administering the Oregon & California Railroad land grant. Those rich timberlands in western Oregon were revested to the government when the Supreme Court determined that the Southern Pacific Railroad, successor to the Oregon and California company, had violated the “actual settler clause” of the land grant by selling parcels of land that were greater than 160 acres. Chamberlain-Ferris placed management of the lands under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office (present-day Bureau of Land Management).

Chamberlain was also a sponsor of Chamberlain-Kahn Act in 1918, which expanded federal attention to the control of venereal disease. The act was based on Portland's success in diminishing the disease during World War I. He was chair of the Senate Committee on the Geological Survey and served on the Military Affairs Committee, where he helped write the selective service law for drafting personnel during World War I.

Oregon’s preference for reformers faded after World War I, and Chamberlain’s Republican opponent, Robert Stanfield, defeated him in 1920. After Chamberlain left office, he remained in Washington, D.C., and served on the U.S. Shipping Board (1921-1923). He practiced law until his death in 1928 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

-

![George Chamberlain]()

George Chamberlain.

George Chamberlain Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no.023377

-

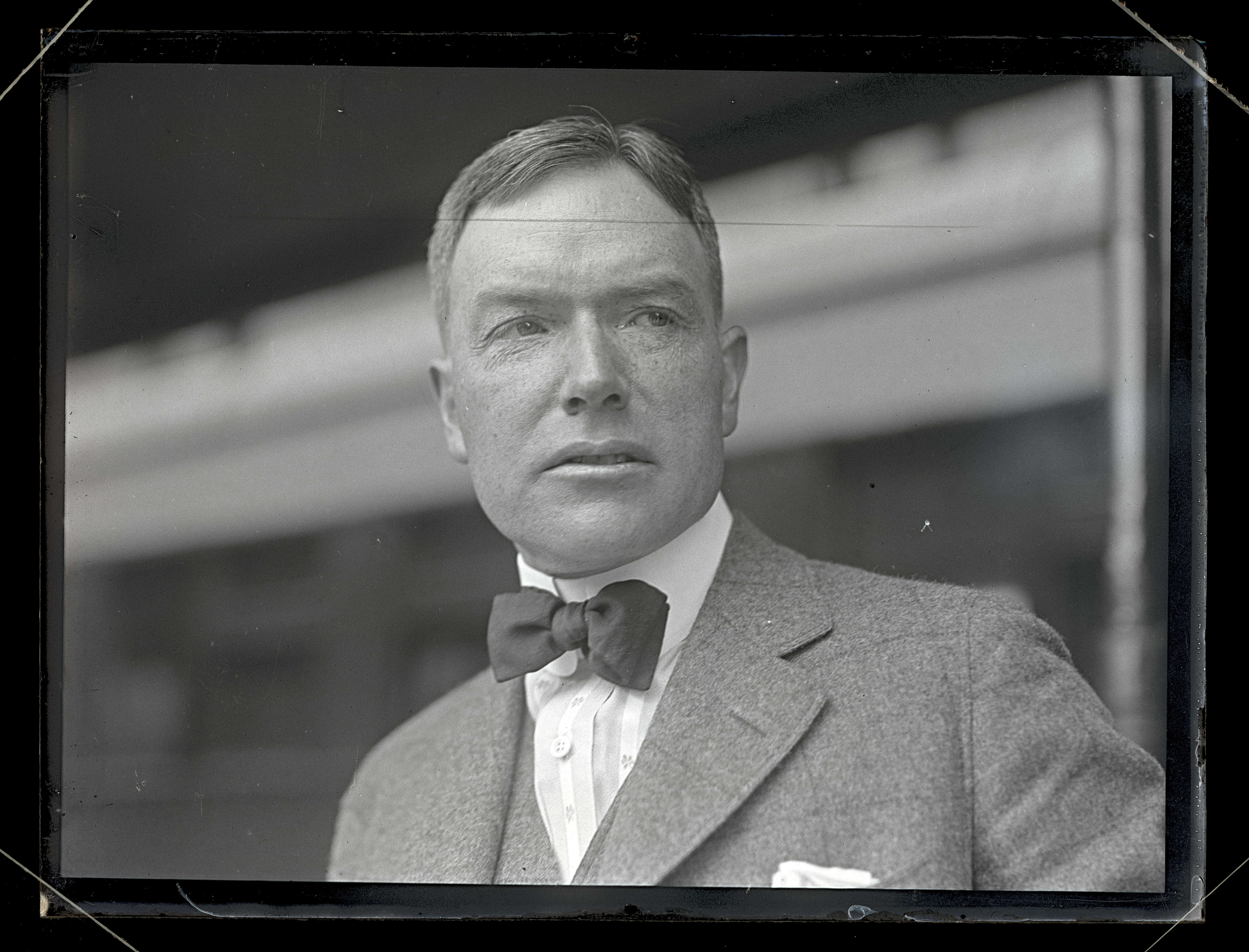

![Sallie and Fannie Chamberlain, c.1910]()

Sallie and Fannie Chamberlain, c.1910.

Sallie and Fannie Chamberlain, c.1910 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no.023377

Related Entries

-

![Charles L. McNary (1874-1944)]()

Charles L. McNary (1874-1944)

Charles Linza McNary represented Oregon in the U.S. Senate from 1917 un…

-

![Oregon and California Lands Act]()

Oregon and California Lands Act

The Oregon and California Lands Act, heralded as a forward-looking cons…

-

![Oswald D. West (1873-1960)]()

Oswald D. West (1873-1960)

Oswald D. West served as Oregon's fourteenth governor, between 1911 and…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Hodges, Adam. World War I in Urban Order. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Johansen, Dorothy O. Empire of the Columbia: A History of the Pacific Northwest. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Robbins, William G. Lumberjacks and Legislators: Political Economy of the U.S. Lumber Industry, 1890-1941. College Station: Texas A and M University Press, 1982.