Oregon's pioneer newspapers were also political organs, advancing their cause in news articles as well as editorials. The most prominent advocates were Asahel Bush of the Oregon Statesman (Salem) and T.J. Dryer of the Oregonian (Portland), Democrat and Whig, respectively. But as the nation entered the Civil War and demands for suppression of "traitors" appeared in the North, it was the editors at smaller weekly papers in Oregon and California who would pay for their outspoken views.

Newspapers in the early nineteenth century were fiercely partisan and attacked their enemies in dismissive terms of contempt. Even before the Civil War, violence was common against abolitionist editors. In 1837, for example, a mob destroyed the presses of the Alton (Illinois) Observer and killed abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy. When war began, violence in the North turned against Southern sympathizers, and federal and local officials closed newspapers across the North and even in distant Oregon.

The most vigorous attacks on press and speech were from military authorities, local politicians with scores to settle, and even mobs. "Editors of hostile journals were put in prison," historians Charles and Mary Beard wrote, "their papers suspended, their newsboys arrested. Peace meetings were broken up and their organizers sent to jail . . . editors accused of holding obstructive views were arrested on military order, and though they were charged with no overt act of any kind, they were held in jail and denied the privilege of a hearing before a civil magistrate."

By war’s end, up to three hundred Democratic newspapers had been suspended at least briefly for anti-Administration or pro-Confederacy statements. Because newspapers were circulated primarily by mail, suppression meant loss of mailing privileges, a death knell to smaller papers.

In Oregon, Gen. George Wright, commander of the Department of the Pacific, proved to be a zealous foe of pro-Southern newspapers. "All these treasonable papers should not only be excluded from the mails and post-offices," he wrote, "but that they should be suppressed entirely." He urged subordinates to seek out offending publications in Oregon and the other states and territories in the Department.

Federal authority authorized the suppression of pro-secession publications; but according to historian Robert Chandler, local pro-Union officials were allowed "to choose the victims." Political partisanship often trumped "subversive language" as a rationale for suppressing newspapers in Oregon and California. Lincoln himself had expressed fear of "the fire in the rear," and, as the war ground on, attempts increased to silence his critics.

In 1860, Oregon U.S. Senator Joseph Lane was the vice-presidential candidate with John C. Breckenridge on the pro-slavery, or "Copperhead," Democratic ticket. A majority of the state’s Democratic papers backed Lane, including the Oregon Democrat (Albany), the Union (Corvallis), Jacksonville Sentinel, Eugene Herald, Roseburg Express, and Portland Daily News. Union backers closed five Democratic newspapers in 1862, starting with the Oregon Democrat, which had been founded in 1859 by Delazon Smith (who later served with Lane in the U.S. Senate). Editor Pat Malone changed the paper's name to the Albany Inquirer, but it was also quickly suppressed.

Other victims of 1862 suppression were the Union (also edited by the hapless Malone), the Jacksonville Southern Oregon Gazette, and the daily Portland Advertiser. The Advertiser was the only Democratic daily newspaper in the state at the time (the Daily News had already folded).

By the following year, nearly all the suppression of newspapers had ended. Congress enacted a policy on arbitrary arrests, and even the energetic General Wright found himself resisting pressure from Union supporters to "arrest every man or woman whose sentiments do not coincide exactly with the government."

Most of the suppressed editors returned to their profession. In their histories, neither Robert Chandler nor George Turnbull report any imprisonment of Oregon editors; the punishment was limited to suppression from the mails.

-

![The State Republican republished this editorial from the Louisville Journal in support of the suppression of "disloyal publications."]()

Clip from The State Republican, Eugene City, June 28, 1862.

The State Republican republished this editorial from the Louisville Journal in support of the suppression of "disloyal publications." Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

-

![]()

The State Rights Democrat, Albany, August 21, 1865.

Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

-

![]()

State Republican, Eugene City, June 28, 1862.

Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

-

![]()

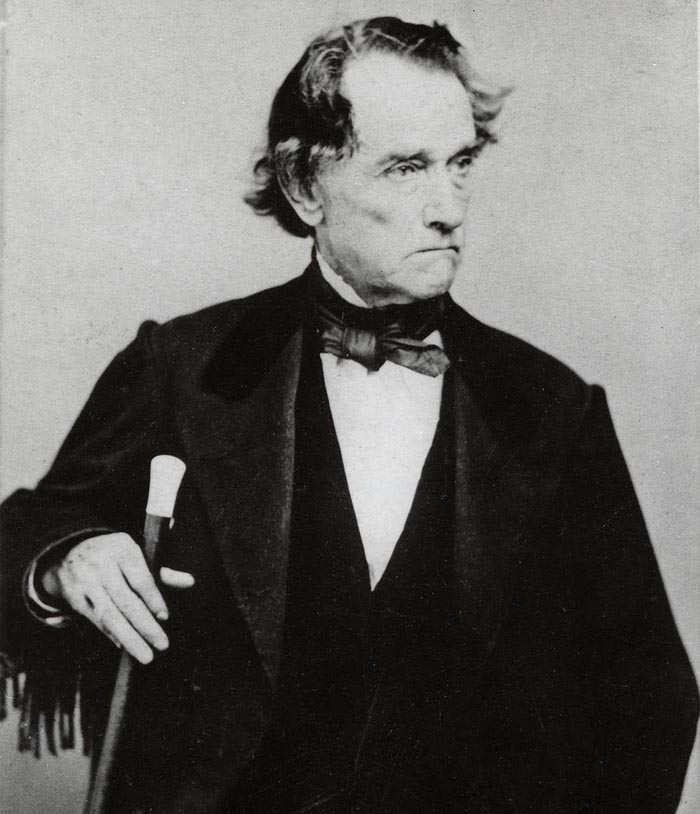

Thomas Jefferson Dryer.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 9149

-

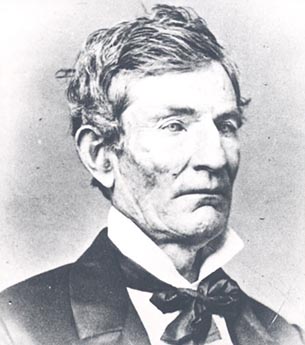

![W.G. T'Vault, c.1860]()

W.G. T'Vault, c.1860.

W.G. T'Vault, c.1860 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg no. 014969

-

![]()

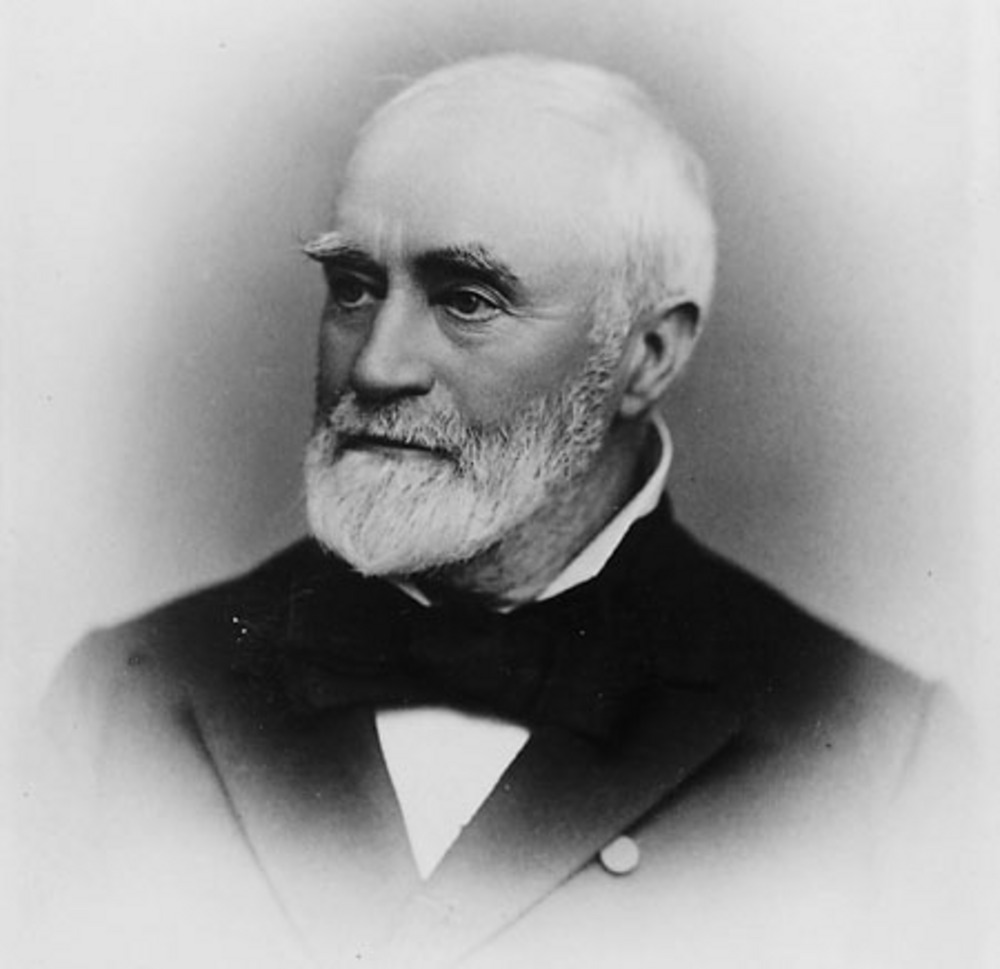

Delazon Smith as U.S. Senator, 1859.

Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office

-

![]()

Asahel Bush.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 70286

-

![]()

Joseph Lane as U.S. Senator, c. 1860.

Courtesy of U.S. Senate Historical Office

-

![]()

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, January 16, 1864.

Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

-

![]()

Clip from the Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, January 16, 1864.

Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

-

![]()

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, December 17, 1864.

Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

-

!["Obituary" mocking former Sentinel editor W.G. T'Vault, whose anti-Union paper the Oregon Intelligencer folded.]()

Clip from the Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, December 17, 1864.

"Obituary" mocking former Sentinel editor W.G. T'Vault, whose anti-Union paper the Oregon Intelligencer folded. Courtesy Historic Newspapers of Oregon

Related Entries

-

![Asahel Bush (1824-1913)]()

Asahel Bush (1824-1913)

Asahel Bush was a key figure during Oregon's formative years, using the…

-

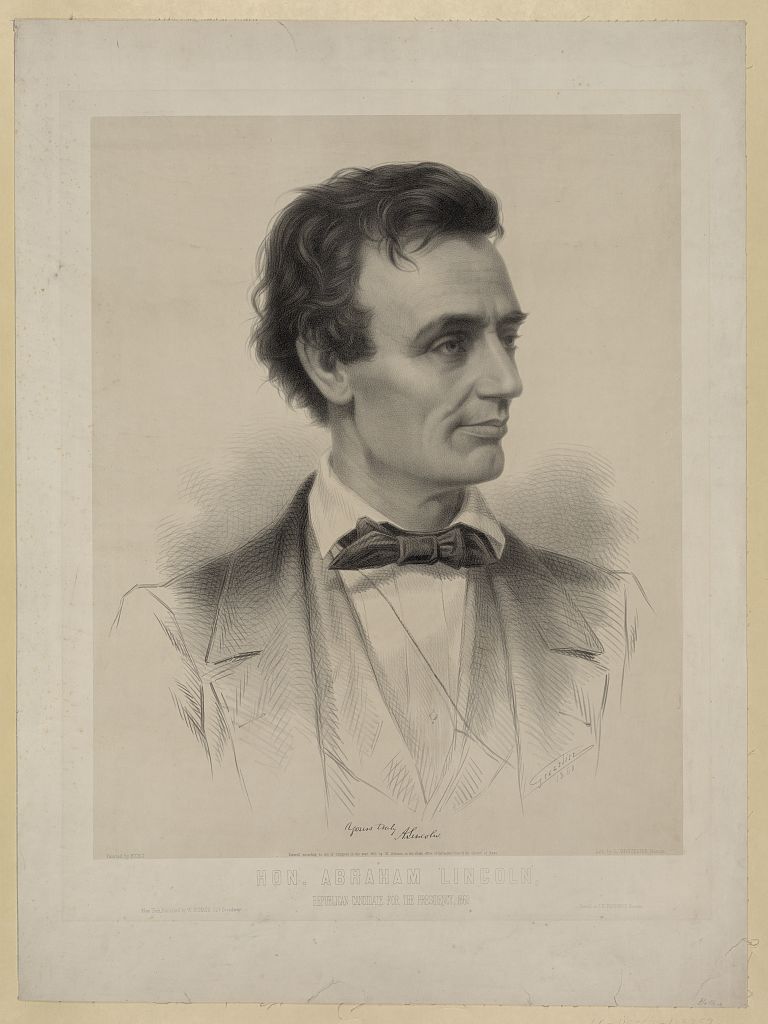

![Election of 1860]()

Election of 1860

The presidential election of 1860 was a turning point in Oregon politic…

-

![Oregon Statesman]()

Oregon Statesman

Throughout its history, the Oregon Statesman has been a chronicler of O…

-

![The Oregonian]()

The Oregonian

The Oregonian, the oldest newspaper in continuous production west of Sa…

-

![Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)]()

Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)

Thomas J. Dryer was the first editor of the Portland Oregonian and an a…

-

![William Green T'Vault (1809-1869)]()

William Green T'Vault (1809-1869)

William Green T’Vault had a wide-ranging career in early Oregon. A truc…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Chandler, Robert J. "Crushing Dissent: The Pacific Coast Tests Lincoln’s Policy of Suppression, 1862." Civil War History 30 (September 1984): 235-54.

Harper, Robert S. Lincoln and the Press. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951.

Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

Turnbull, George S. History of Oregon Newspapers. Portland: Binfords & Mort, 1939.