The most famous train holdup in Oregon was a ham-fisted disaster. On October 11, 1923, an attempt by brothers Ray, Roy, and Hugh DeAutremont to rob a Southern Pacific Railroad train at Tunnel 13, high in Oregon’s Siskiyou Mountains, ended with a burned-out mail car, no payout, and four men dead. The episode generated pioneering efforts in forensic criminology, and after a nearly four-year-long manhunt led by a team of Southern Pacific Railroad and U.S. postal investigators, the DeAutremonts were tracked down and sentenced to life in prison. Some writers portrayed the crime as America’s “last great train robbery”—a misnomer that has lasted, although no loot was taken and such robberies continued into the 1930s.

Twins Ray and Roy DeAutremont were twenty-three years old in 1923 when they and their nineteen-year-old brother Hugh began planning a train robbery. Seven years earlier, the twins had left their hardscrabble New Mexico home after their father had left the family, often riding freight trains from place to place and making do with itinerant jobs such as picking fruit. In 1920, Ray—who had joined the radical Industrial Workers of America, or IWW, during World War I—was arrested in Vancouver, Washington, during one of the nation’s Red Scare sweeps of alleged Bolsheviks. He rejoined his twin in 1921 after spending a year in prison.

In 1922, Hugh DeAutremont graduated from high school, where he had been a good student and quarterback on the football team. He joined the twins at a northern Oregon logging camp, where they worked under assumed names. By mid-1923 they had decided to rob the Southern Pacific Railroad’s San Francisco-bound express while it was stopped at Siskiyou Tunnel 13 to test the brakes. The train, they believed, would be carrying several thousand dollars in cash.

Tunnel 13, excavated in 1887 through more than a half-mile of bedrock, lay directly below Siskiyou Pass at the highest point along the Southern Pacific main line between Portland and southern California. The steep uphill grade from Ashland required an extra engine to get the train to the tunnel’s east portal, on the north side of the pass. There, at the busy Siskiyou workstation, trainmen conducted brake tests and other safety functions. The DeAutremonts had discovered a cabin in the timber above the tunnel and used it as a base of operations, stockpiling food, firearms, a full box of dynamite, and a plunger-type detonator.

Late on the morning of October 11, 1923, while Ray DeAutremont remained at the west (south side) portal with the dynamite, his brothers armed themselves with a shotgun and Colt .45 automatic pistols and hiked over the pass to the other end of the tunnel to wait for the train. At about 12:30 p.m., southbound Train #13—the engine, mail car, four baggage cars, and three passenger cars—arrived at the east portal, where Roy and Hugh had concealed themselves in the brush. After the helper engine uncoupled and switched onto a spur track, but before Southern Pacific engineer Sidney Bates and his fireman Marvin Seng could perform the brake test, Roy and Hugh climbed aboard the locomotive. They forced Bates to pull through the tunnel, with the engine stopped just outside the far portal.

It was there that the brothers’ plans fell apart. They yelled at the postal clerk, Elvyn Dougherty of Ashland, to unlock the door of the mail car, but he refused and locked himself inside. Instead of wiring a few sticks of dynamite to blow open the door, Roy used the entire box, and the explosion killed Dougherty instantly. The mail car—full of mail but carrying no currency or gold—became a fiery, smoke-filled inferno. Thinking that the explosion was the engine’s boiler, Coyl Johnson, a brakeman from Ashland, walked through the tunnel to investigate. Just as he exited the west portal, the brothers shot him. With more Southern Pacific employees from Siskiyou Station soon to arrive, they also shot Bates and Seng. All of the men died.

Fleeing into the woods to a well-stocked hideout deep in the dense brush, the DeAutremonts waited undetected for nearly two weeks. Armed posses searched the rugged country, U.S. Army and Forest Service fire-patrol planes circled overhead, and National Guard troops checked houses and barns along Pacific Highway to the south. The murderers seemed to have vanished.

Pioneering forensic scientist E. O. Heinrich, from the University of California, Berkeley, examined the evidence gathered from the scene by Southern Pacific and postal investigators. Focusing on stains on a pair of coveralls that had been left behind, Heinrich determined that they were Douglas-fir pitch. The sawdust in the pockets was also from Douglas-fir, indicating that the owner likely had worked in the Northwest woods. Heinrich also found a slip of paper, faded and blurred from washings, jammed into a pencil pocket. He used iodine vapor to determine that it was a registered mail receipt signed by Roy DeAutremont.

With that evidence, the DeAutremonts brothers were identified even before they had left their Siskiyous hideout. Despite wanted posters showing their faces, they traveled south undetected and split up. They would remain at large for four years before being arrested in 1927. Hugh joined the U.S. Army and was recognized by his sergeant while in the Philippines. His arrest put photographs of Roy and Ray back into the newspapers, and someone recognized them in Steubenville, Ohio. The FBI arrested and returned the twins to Oregon, where they stood trial in Jackson County. The three brothers signed confessions in order to escape almost certain death sentences—a deal that outraged railroad and postal employees who wanted to see the men hang.

By 1950, Roy’s mental condition had deteriorated, and he spent his remaining years in the Oregon State Mental Hospital. He died in 1983. Hugh was paroled in 1959 but died of cancer three months later. In 1961, Ray was granted parole and worked as a custodian at the University of Oregon. He died in 1984.

The story of the robbery has been kept alive in the media, in literature, and in film. The attack occurred near the end of the train-robbing era in the United States, when railroads had increased security to a level that made hijacking trains dangerous and unprofitable for thieves. The DeAutremonts’ attempt made national headlines and was dubbed “the last great train robbery,” a nod to its rarity and the violent audacity of the attempt. Other train robberies during and after the same period also carried the title. In Oregon, the Siskiyou Pass Tunnel attack was among the last recorded train holdups and one that remains firmly in the state’s cultural memory.

-

![]()

Wanted poster, distributed June 1, 1924.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society 1988.11-8.5, MS 672 (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

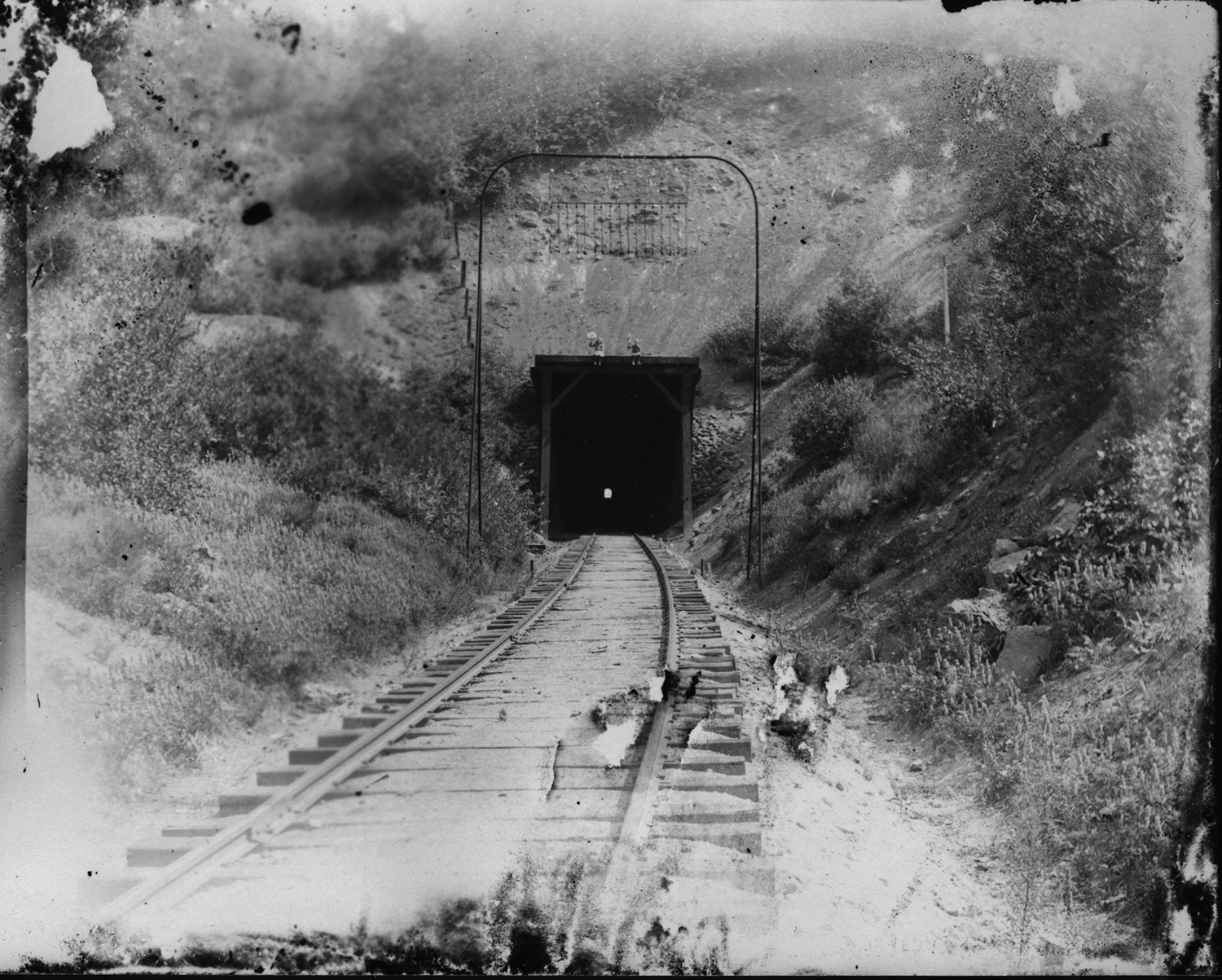

Tunnel 13, Siskiyou Pass.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society 1977.117.14, #034468 (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

Southern Pacific crews work on Tunnel #13.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society 1988.4-2, #019337 (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

Southbound freight enters the north end of Tunnel 13, c. 1912..

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

Temporary buildings for railroad workers at the north entrance of Tunnel 13, 1886-1887.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society 1963.123.12, #006216 (via the Smithsonian) -

![]()

The DeAutremonts exploded this mail car, killing Elvyn Dougherty.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society #06791 (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

One of the victims of the robbery was Elvyn E. Dougherty, here with his family.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

Wanted circular from the U.S. Post Office, issued 1926.

Courtesy National Postal Museum, 1990.0563.3 -

![]()

The twins, Roy and Ray DeAutremont, 1923.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 373G0050 -

![]()

Ray and Roy DeAutremont at the Jacksonville Courthouse, 1927.

Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society #014431 (via Smithsonian) -

![Pictured here from left are entertainer Pinto Colvig, defendant Hugh DeAutremont, jailer Ike Dunford, and an unknown man identified as Mr. Luzinoff. Note: Jacksonville was the seat of Jackson County up through 1927, when it was moved to Medford.]()

Hugh DeAutremont (second from left) at the Jackson County Courthouse in Jacksonville for his trial..

Pictured here from left are entertainer Pinto Colvig, defendant Hugh DeAutremont, jailer Ike Dunford, and an unknown man identified as Mr. Luzinoff. Note: Jacksonville was the seat of Jackson County up through 1927, when it was moved to Medford. Courtesy Southern Oregon Historical Society #010939 (via Smithsonian) -

![]()

Hugh DeAutremont with U. S. marshals, 1958, to enter a plea in federal court..

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot1284_3078_1 -

![]()

Ray DeAutremont at Tunnel 13 in 1973.

Courtesy National Archives -

![DeAutremont painted this landscape while incarcerated at the Oregon State Penitentiary.]()

Painting titled, "Solitude, Silence and Mountains," by Ray DeAutremont, 1956.

DeAutremont painted this landscape while incarcerated at the Oregon State Penitentiary. Oregon Historical Society Museum Collection, 82-193.1,.2

Related Entries

-

![Ashland]()

Ashland

Ashland, a city of 21,360 people in Jackson County, is situated in the …

-

![Siskiyou Pass]()

Siskiyou Pass

Siskiyou Pass, including the 4,310-foot-high Siskiyou Summit of Interst…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Mangold, Scott. Tragedy at Southern Oregon’s Tunnel 13: DeAutremonts Hold Up the Southern Pacific. Cheltenham, UK.: History Press, 2012.

Chipman, Art. Tunnel 13: The Story of the deAutremont Brothers and the West's Last Great Train Hold-Up. Pine Cone Press, 1977.

Horton, Kami. "Murder On The Southern Pacific." Oregon Experience. Oregon Public Broadcasting, May 4, 1025.