As an impressionable and imaginative girl growing up in Illinois, Eva Emery pored over every historical novel written by Sir Walter Scott. Within the pages of Waverley, Rob Roy, and Ivanhoe, she found an inspiring concoction of chivalry, adventure, romance, and cross-cultural conflict. Later, as a student at Oberlin College in the 1870s, she delighted in the epic poetry and literature of Homer and Hesiod. These works—as well as those of Irving, Longfellow, Carlyle, Emerson, and Fuller—would encourage the talented and exuberant writer to compose what she believed were America's epic stories: the contested settlement of the Northwest Coast in the 1820s, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and the Overland Trail migrations. Pioneering the genre of historical fiction in the Pacific Northwest, Dye adopted a style that was a curious blend of fact, fiction, biography, and romance.

Eva Lucinda Emery was born in Prophetstown, Illinois, to Cyrus and Caroline Trafton Emery. She began writing poetry at a young age, encouraged by her father's storytelling and her deceased mother's poems and schoolbooks. At age fifteen, the Prophetstown Spike published "Dreamland," and soon other midwestern newspapers issued her poems under the pseudonym "Jennie Juniper." Despite her father's opposition, Emery was determined to attend college. She taught primary school in Prophetstown and ultimately raised the funds for one year's preparatory training at Oberlin in Ohio.

Oberlin opened new intellectual worlds for the inquisitive young woman, who took courses in the classics and submitted poetry to the Oberlin Review, the student newspaper. Emery joined the Ladies' Literary Society and was the poet laureate of her class. Like many white, middle-class women of her generation, she found a purpose in the temperance and suffrage movements, moral and political causes that would inspire both her writing and activism in her later years.

In 1882, Emery graduated from Oberlin and married classmate Charles Henry Dye, a native of Fort Madison, Iowa. In 1890, the Dyes migrated to Oregon City, Oregon, where Charles developed a thriving real estate and contract law practice. Charles's financial success allowed Dye to concentrate on her writing and enabled them to raise four children. The Dyes soon helped organize the Willamette Valley Chautauqua Association, which brought religious and educational speakers to Gladstone Park every summer for over thirty years.

Almost immediately after arriving in Oregon, Dye began a chronicle of the turbulent history of American Protestant missionaries and pioneers and their British fur-trading counterparts in the Oregon Country. Her first book, McLoughlin and Old Oregon (1900), represented more than the romanticized biography of Dr. John McLoughlin, chief factor of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department. As in all of her books, Dye highlighted cross-cultural interactions and themes as well as the roles and activities of women, although she frequently embellished the text with inventive dialogue and her characters often possessed the flatness and simplicity of heroic archetypes.

Dye's success with McLoughlin encouraged further study of America's epic adventures. She turned to the nation's empire-building in the late eighteenth century and found her heroes in William Clark and his brother, Revolutionary War surveyor, scout, and Indian fighter George Rogers Clark. The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (1902) was a collective biography of the Clark family and a celebration of westward expansion. The Lewis and Clark Expedition framed a central part of her narrative. The text brought Sacagawea, the young Shoshone woman who accompanied the explorers on their eighteen-month trek, to general readers for the first time.

The Lewis and Clark journals depict Sacagawea as useful in pointing out landmarks in territory with which she was familiar, helpful in finding food for the explorers, and clear-headed in a near-disastrous incident with one of the pirogues. The Conquest remains true to the expedition journals in these aspects, but Dye believed Sacagawea represented traits of nineteenth-century true womanhood. She embellished Sacagawea's character with scenes of domestic tranquility and imagined her state of mind, portraying Sacagawea as a youthful mother and civilizing force among male adventurers. Although critics have erroneously claimed that Dye's depiction of Sacagawea derived from her desire to promote the suffrage movement, her focus was on Sacagawea as an ideal maternal figure, a symbol of pioneer motherhood that the author later would promote.

Dye published two works of romantic fiction: McDonald of Oregon: A Tale of Two Shores (1906) and The Soul of America: An Oregon Iliad (1934). Her lasting legacy, however, endured in the area of research. She was determined to bring her stories to life with as much detail and veracity as possible. Few pioneer descendants were beyond her reach, and she assiduously recorded and preserved their recollections before translating them into her own epic vision. Pursuing every lead, she unearthed valuable diaries and documents of the West's early explorers, as well as extant letters and pioneer reminiscences that she donated to libraries and historical societies.

In 1903, Dye was instrumental in discovering several of William Clark's expedition notebooks, letters between Lewis and Clark and Thomas Jefferson, and fifty of Clark's maps. It was these indefatigable research efforts, together with her lifelong writing and enthusiastic public speaking on the western past, that made Dye a popular and respected champion of regional history and literature.

-

![]()

Eva Emery at age nineteen, March 1874.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 1017, b.1, f.3, OrHi 84299

-

![]()

Eva Emery Dye graduation photo from Oberlin College, 1882.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org Lot 1017, b.1, f.3, Neg #37244

-

![]()

Portrait of Eva Emery Dye as a baby, c.1855.

Cased photographs collection, Org. Lot 1414, Box 239, 0239S001, Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland, Oregon.

-

![]()

Eva Emery Dye.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 87523

-

![]()

Eva Emery Dye.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org Lot 1017, box 1, f4

-

![]()

Letter from Oregon Equal Suffrage Association, 1906.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Mss432_B3F5_004

Related Entries

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

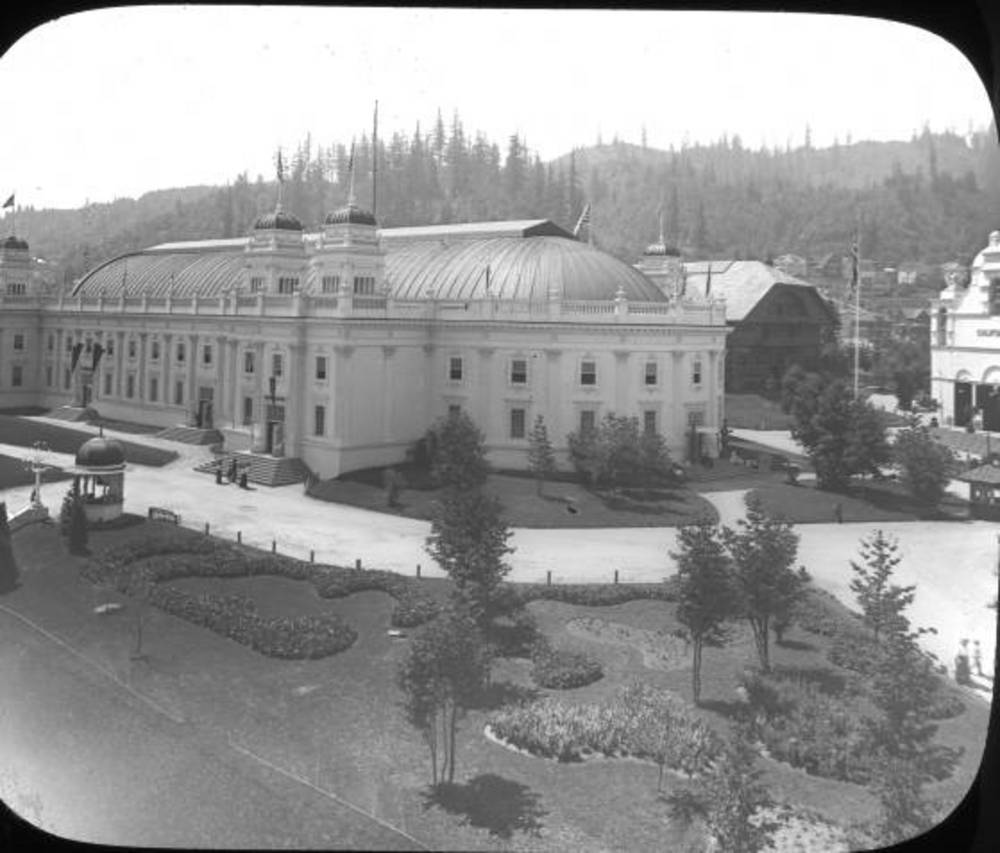

![Lewis and Clark Exposition]()

Lewis and Clark Exposition

Portland staged its first and only world's fair from June 1 through Oct…

-

![Sacagawea]()

Sacagawea

Sacagawea was a member of the Agaideka (Lemhi) Shoshone, who lived in t…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Browne, Sheri Bartlett. Eva Emery Dye: Romance with the West. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2004.

Swanson, Kimberly. "Eva Emery Dye and the Romance of Oregon History." The Pacific Historian 29:4 (1985): 59-68.