On February 22, 1886, approximately forty men gathered in Oregon City at the McLoughlin House on South Main Street, then a lodging house known as the Phoenix Hotel, and voted to rid the town of its Chinese population. Most of the men assembled at the Phoenix were members of the local Knights of Labor and Anti-Coolie League. Their elected leader, Nathan L. Baker, was from Portland and a prominent member of the League.

The men marched to the Washington Hotel, where Chinese mill workers slept, wrested the men from their beds, and marched them to the Willamette River. Between forty and fifty-five workers were forced aboard the steamboat Latona, which carried them to Portland. Twelve men were arrested for the expulsion, including Baker and Al White, an Oregon City man who was later named as a leader of the mob. None were brought to trial.

In the winter and spring of 1886—when the nation was suffering from an economic depression, growing labor militancy, and a nationwide debate over free labor—the Northwest experienced a rampant anti-Chinese fervor. The completion of the transcontinental railroad to Portland in 1883 ended an associated building boom, making economic conditions particularly dire in the region. Thousands of white men, many of them unskilled laborers, had moved west expecting to live the promise of Manifest Destiny, only to find that they were too late. Itinerant labor organizers and demagogues traveled along the West Coast insisting that Chinese “coolie” laborers were occupying what should be white jobs. Many misperceived Chinese workers as slaves, and some billed the anti-Chinese crusade as post-Civil War abolitionism. Some businesses responded by firing their Chinese employees. This was the case in Oregon City, where most of the town's Chinese residents worked in the Jacobs Bros. woolen mill. Responding to pressure from the community, the mill had begun replacing Chinese workers with white laborers several weeks before the expulsion.

Although anti-Chinese violence in Oregon never escalated to the point that it did in Seattle, Tacoma, and parts of northern California, the Oregon City incident was not an isolated one in the state. That same evening, the towns of Beaver Valley and Butteville, on the Willamette River, forced their Chinese neighbors aboard a boat headed to Portland. Anti-Chinese pogroms also occurred in East Portland, Albina, Mount Tabor, and Guild's Lake, and several Chinese laundries were the targets of dynamite attacks.

On the night of the Oregon City expulsion, 3,500 people paraded through the streets of Portland, carrying signs insisting that "Slavery must not exist here in 1886" and "The Chinese must go." A February 13, 1886, meeting of an Anti-Chinese Congress in Portland had fueled the flames as participants resolved that all the Chinese in Oregon had to leave for San Francisco by March 24.

Nonetheless, many Oregonians were not swayed by the rhetoric and worked diligently to quell the potentially explosive sentiments, most notably Harvey Scott, editor of The Oregonian. Partially due to the counter-efforts of Harvey Scott and others, the planned mass expulsion never materialized, and Oregon evaded the larger anti-Chinese upheaval that Washington and California experienced during the same period.

-

![East Side Railway cars passing on Main St. in Oregon City, 1890s.]()

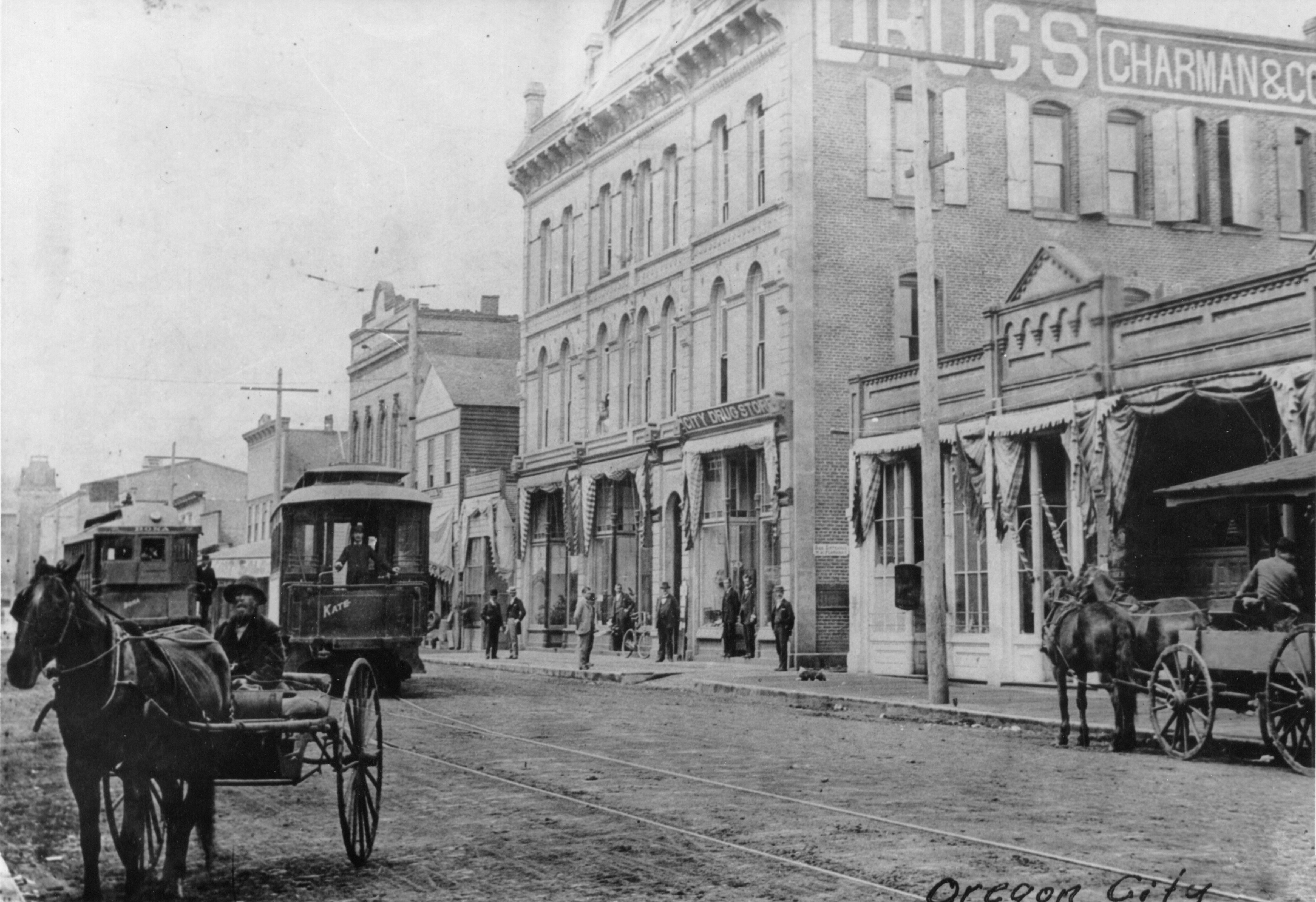

Oregon City, East Side Railway cars, 1890s.

East Side Railway cars passing on Main St. in Oregon City, 1890s. Courtesy Richard Thompson

-

![The graphic condemns the attack on Chinese residents in Oregon (likely an immediate response to the Oregon City violence), acknowledging its violation of the 1868 Treaty with China and the inhumanity of the expulsion.]()

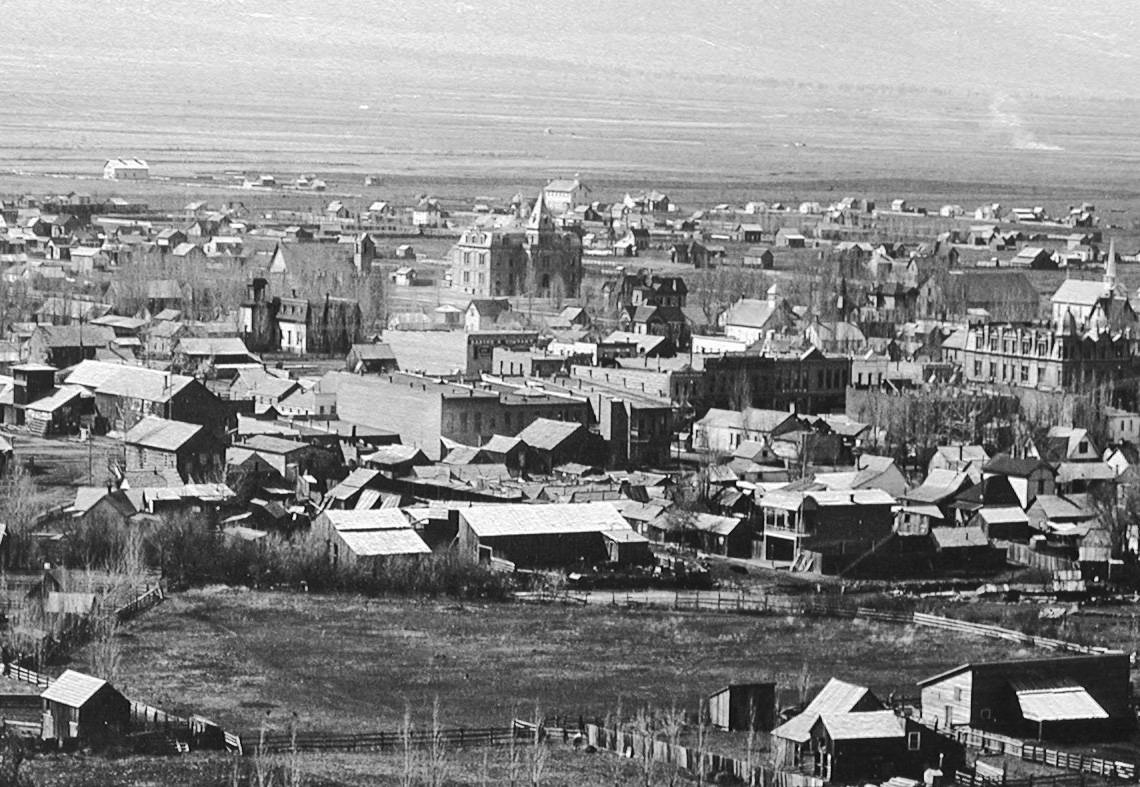

"Hobson's Choice -- you can go or stay." Puck Magazine, February 1886.

The graphic condemns the attack on Chinese residents in Oregon (likely an immediate response to the Oregon City violence), acknowledging its violation of the 1868 Treaty with China and the inhumanity of the expulsion. Courtesy Library of Congress

Related Entries

-

![Baker City Chinatown]()

Baker City Chinatown

For over seven decades, Baker City had an area referred to as Chinatown…

-

![Chinese Americans in Oregon]()

Chinese Americans in Oregon

The Pioneer Period, 1850-1860 The Cantonese-Chinese were the first Chi…

-

![Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek]()

Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek

Of the many crimes and injustices committed against early Chinese immig…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

McClain, Charles J., Jr. “The Chinese Struggle for Civil Rights in 19th-Century America: The Unusual Case of Baldwin v. Franks.” Law and History Review 3 (Fall 1985), 357-358.

Schwantes, Carlos A. “Protest in a Promised Land: Unemployment, Disinheritance, and the Origin of Labor Militancy in the Pacific Northwest, 1885-1886.” The Western Historical Quarterly 13 (Oct. 1982), 373-390.

Wong, Rose Marie. Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.