During the late summer of 1910, a searing drought combined with high-velocity August windstorms to create a fiery holocaust in the forests of the Pacific Northwest. The fires also laid a major challenge at the feet of the newly established U.S. Forest Service, which was charged with fighting the fires.

Most of the firefighting action occurred in Idaho, Montana, and Washington, but Oregon's forests also were tinder dry that year. Lightning storms, careless hunters, and homesteaders who set fires deliberately in order to find work on the fireline caused an estimated half a billion board-feet of Oregon timber to go up in flames. The fires would have significant effects on future forestry policy.

The story of what became known as the Big Burn or Big Blow-up in Montana and northern Idaho is well documented: over eighty people were killed; towns were incinerated, including one-third of the town of Wallace, Idaho; and hundreds of thousands of acres of forest burned. Smoke from the fires darkened skies as far away as New England.

The narrative of the 1910 fires includes the heroic actions of Rangers Joe Halm and Ed Pulaski, who saved their crews from death, and the compelling image of a group of refugees who barely escaped the flames as their train crossed a burning high trestle.

In Oregon, the threat to life and property was serious and the physical impact was substantial. The secretary of war dispatched U.S. Army troops to help northwestern states combat the flames, and hundreds of soldiers were sent by rail to Oregon from their annual summer encampment at American Lake, Washington.

An unusually early fire in mid-July in the upper Santiam River had hinted at what lay ahead. Early August thunderstorms ignited the first big fires, which burned in northeastern Oregon on the Wallowa and Whitman National Forests (now the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest). The small community of Medicine Springs nearly burned over in a comparatively small, 800-acre fire. Other fires torched the Blue Mountains rangelands, leaving no food for the thousands of sheep that were being driven to their annual summer grazing areas.

Other big August fires occurred on the Deschutes and Crooked River (Ochoco) Forests and on the eastern slope of Mount Hood. Closer to Portland, a fire burned in the timber near Estacada, where a woman perished trying to save belongings from her burning cabin. To the south, large fires burned much of the Jackson Creek watershed, in the Umpqua National Forest, and the Limpy Creek area near Grants Pass, in the Siskiyou National Forest.

In mid-August, a lightning storm ignited the largest and longest-burning of Oregon's 1910 fires on the Crater National Forest (now Rogue River-Siskiyou). More than fifteen large fires (over 1,000 acres) burned both east and south of Medford. The rapidly spreading Brushy Hill Fire in the Siskiyou Mountains a few miles from Ashland caused merchants to close their businesses, and all able-bodied men "assembled on the fireline to save the city." While leading an inexperienced crew of townsmen, Ranger Claude Dubois, whose hands were badly burned, reportedly went without sleep for fifty-five hours.

In the Cascade Range, a fire burned much of the South Fork of the Rogue River Canyon near Prospect, and another torched several thousand acres of dense forest west of Union Creek. Careless berry-pickers caused a large fire on Huckleberry Mountain, just west of Crater Lake National Park, and arsonists set blazes close to the town of Butte Falls.

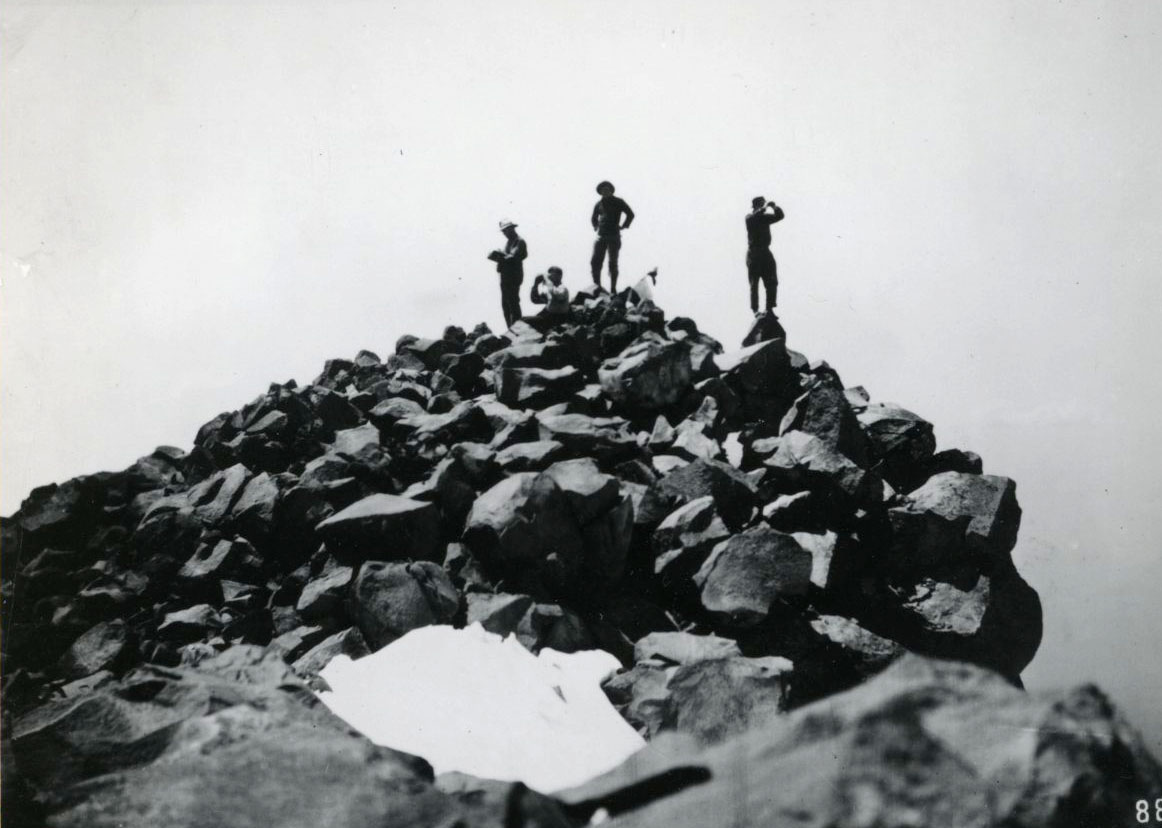

The Cat Hill fire east of Butte Falls was the biggest conflagration in the Crater National Forest. Burning at least 30,000 acres, the fire swept from the slopes of Mount McLoughlin northward along the spine of the Cascades. The Oregonian described the situation at Cat Hill as "almost like a tremendous explosion, scattering sheets of flame in all directions." Forest Supervisor Martin Erickson and his crew of Greek railroad laborers took refuge in the shallow Twin Ponds "to keep from being roasted." Arriving at the Medford depot in the smoke-filled Rogue Valley on August 20, companies E and M of the 1st Infantry headed to join firefighters at Cat Hill and elsewhere.

In many cases, firefighting efforts simply helped deflect the flame fronts from ranches, towns, and valuable stands of timber. The fires were not successfully suppressed until the fall rains provided relief.

The legacy of the 1910 fires was an aggressive policy of fire detection and suppression—all forest fires, anywhere and everywhere—in the West. The new policy ignored the role that low-intensity periodic fire had played for centuries in the region, and Oregonians see the result today in the unnaturally dense stands of trees and brush that carpet much of the public forests—forests that have become prone to disease, insect infestation, and, ironically, destructive high-severity fire.

-

![]()

Guards watch for fires on the summit of Mt. McLoughlin, August 1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019365

Related Entries

-

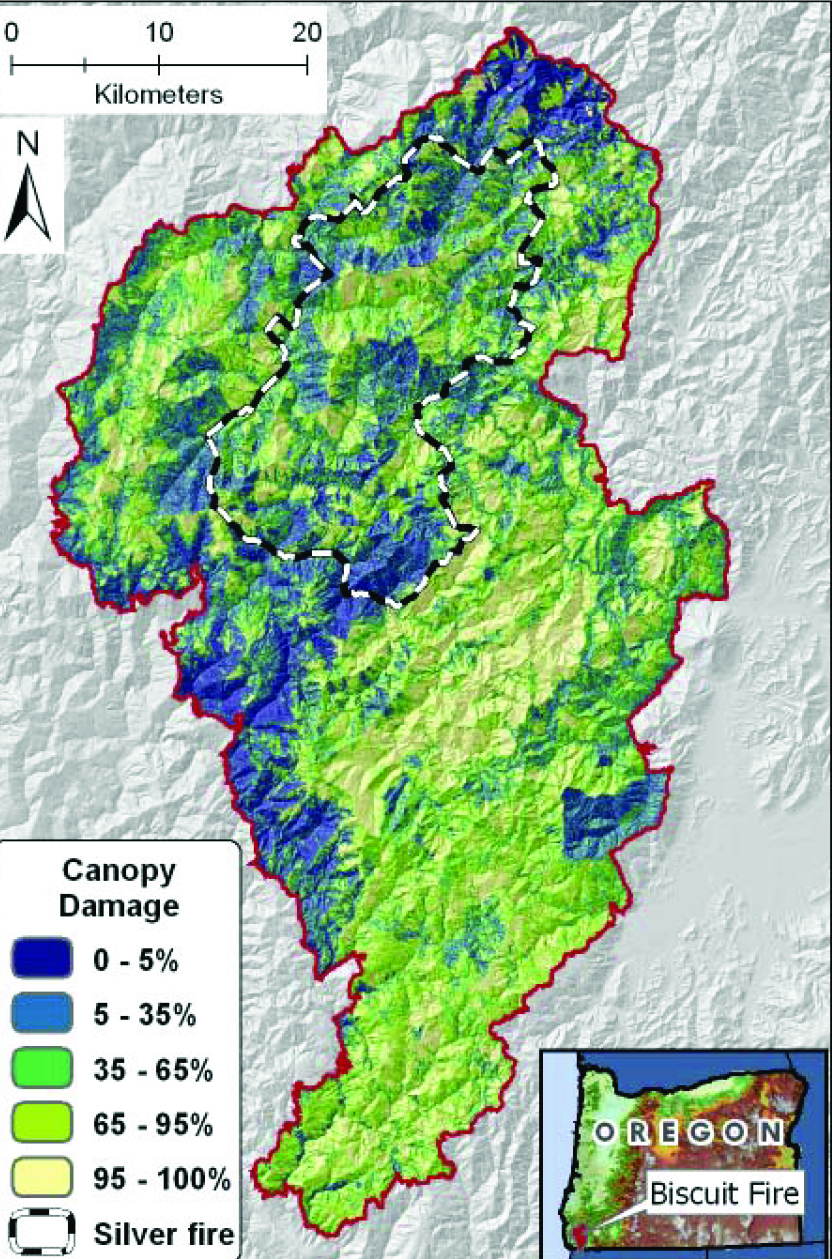

![Biscuit Fire of 2002]()

Biscuit Fire of 2002

On July 13, 2002, a series of electrical storms passed over southwester…

-

![National Forests in Oregon, 1892 to 1933]()

National Forests in Oregon, 1892 to 1933

The first forest reserves in the state were established in 1892-1893, a…

-

![Oxbow Ridge Fire of 1966]()

Oxbow Ridge Fire of 1966

Oregon’s forests were extremely dry in August 1966. Hot east winds bega…

-

![Tillamook Burn]()

Tillamook Burn

The Tillamook Burn was a catastrophic series of large forest fires in t…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Brown, Carroll E. History of the Rogue River National Forest, Vol. I: 1893-1932. Medford, Ore.: USDA Forest Service, 1969.

Egan, Timothy. The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 2009.

Pyne, Stephen J. Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910. New York: Viking, 2001.

Williams, Gerald W. The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest: A History. Corvallis: Oregon State University press, 2009.