During the Civil War era, tens of thousands of people immigrated to the Pacific Northwest. While they avoided the war, they faced conflict with Native people whose homelands were being threatened. On the Applegate Trail, the new settlers met particular resistance from the Modocs, and the Oregon legislature called on the U.S. Army to build a fort in south-central Oregon. Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord, who was in command of the army's Department of Oregon (1862-1865), approved the creation of the post. In 1863, Captain William Kelly led C Troop, First Oregon Cavalry, into the Wood River Valley to build and occupy Fort Klamath.

The fort was constructed in a particularly scenic spot. As an army surveyor wrote, “There can be no question of the fitness of the place selected for the new fort if the only considerations are the health of the troops and the concern of their support.” Over a thousand acres were selected for the fort proper, with more than three thousand acres designated as a hay reserve to supply the cavalry’s mounts.

One of the first buildings constructed was a sawmill, which was used to produce the material to build officer quarters, barracks, storehouses, hospital, a bake house, an arsenal, and stables. The buildings surrounded a parade ground with a 125-foot-high flagpole. By the time the post was abandoned in 1886, it had thirty-nine buildings, including a hotel and a theater.

In 1864, the post was near the site of a treaty between the U.S. government and the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Paiute Tribes. It was this treaty, signed in Council Grove, which created the Klamath Reservation (just south of the Fort) and denied the Modocs their traditional homeland along the Lost River, leading to the Modoc War in 1872-1873. Throughout the remainder of the 1860s, soldiers from Fort Klamath played a major role in patrolling wagon routes across southeastern Oregon, skirmishing regularly with Northern Paiute Indians in what was known as the Snake War.

The fort usually had one or two troops of cavalry present. With the enlistment of the First Oregon Infantry into federal service, a company of infantry was added in 1865 to help build a military road across the Cascade Mountains, which created an easier route to the western valleys and stimulated more white movement into the area.

With the end of the Civil War, the regular army returned to soldier in the Pacific Northwest, and the Oregon Volunteers were replaced by men of the First U.S. Cavalry Regiment. At the same time, the Modocs, unhappy on the Klamath Reservation, often slipped away to their homeland on Lost River. In 1869, Indian Agent Alfred B. Meacham persuaded them to return to the reservation, promising to help the tribe gain its own reservation on Lost River.

The U.S. government did not keep Meacham’s promise, partly because a new Indian agent was appointed. Captain O.C. Knapp, who drank to excess and was insensitive to the Indians’ needs, was removed in relatively short order; but the damage had been done. The new Indian agent, Thomas Odeneal, was more sympathetic, but the Modocs still refused to live on the Klamath Reservation.

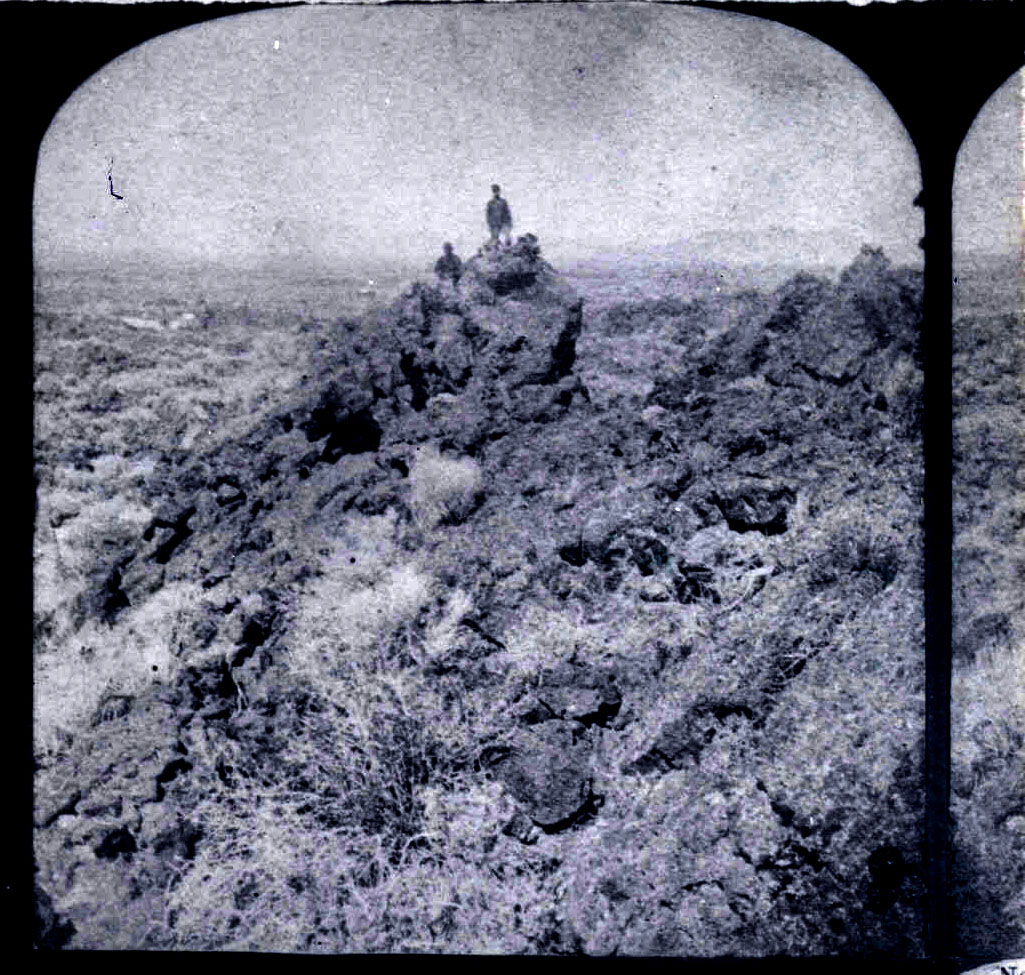

When the Bureau of Indian Affairs called on the army to remove the Modocs from their homeland on Lost River and return them to the reservation, the troops at Fort Klamath took to the field. They established a temporary camp on Lost River to watch the Modocs, but then received the order to force the Indians to return to the Klamath Reservation. General R.S. Canby, commander of the Department of the Columbia, issued the order and added that “the force employed should be so large as to secure the result at once and beyond peradventure.”

In late November 1872, the fort’s commander, Major John “Uncle Johnny” Green, ordered only one troop of cavalry to join with a company of militia from Linkville (present-day Klamath Falls). Rather than overwhelm the Indians with the size and strength of the force, as Canby had intended, the outnumbered cavalry allowed the Indians to achieve tactical advantage.

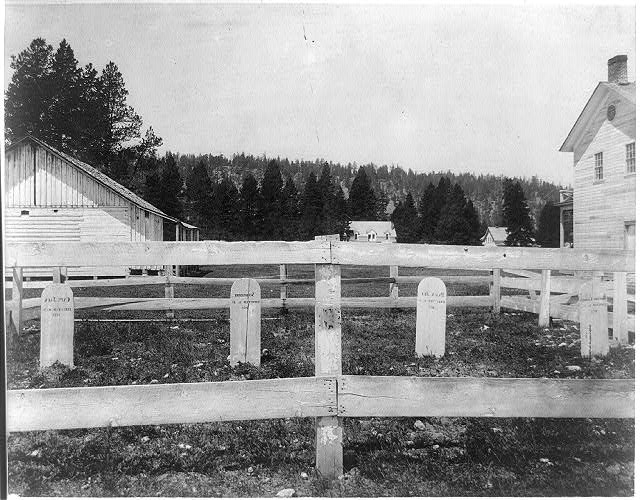

Fort Klamath was a supply depot during the subsequent war, which lasted until the spring of 1873 when the last of the Modocs surrendered. The leaders were held as prisoners and taken to Fort Klamath for trial. Of the six men tried for murder—General Canby had been killed during a peace council—four were found guilty. On October 3, 1873, Captain Jack and three other Modocs were hanged and buried near Fort Klamath.

President Grover Cleveland ordered the fort closed. The post closed in 1887, the last of the soldiers left in 1890, and Fort Klamath became part of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Eight acres of the original site are now a county park. There is a small museum on the grounds, along with the graves of the four Modocs who were executed in 1873.

-

![Fort Klamath, soldiers]()

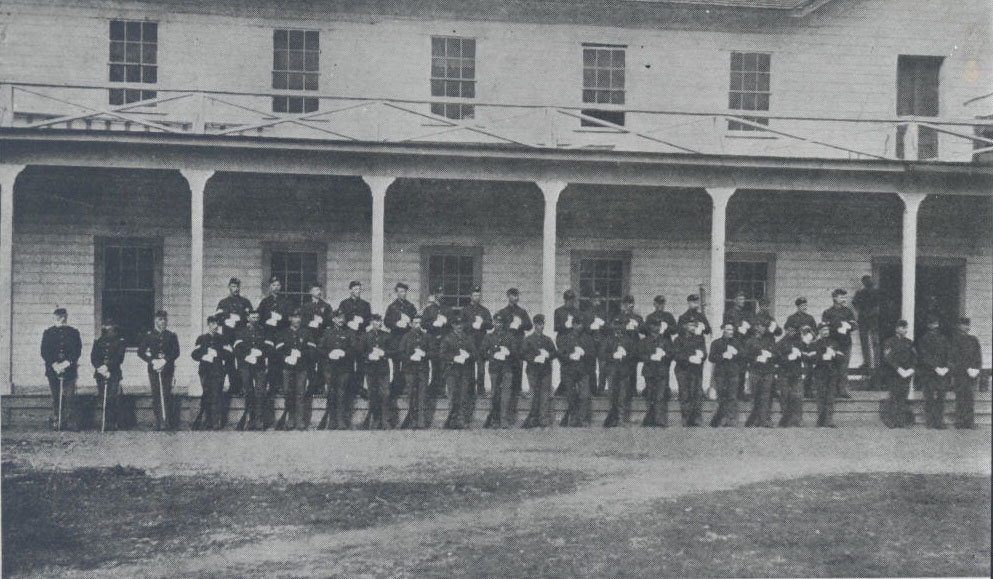

Fort Klamath, soldiers.

Fort Klamath, soldiers Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no. 1678

-

![Fort Klamath parade grounds]()

Fort Klamath parade grounds.

Fort Klamath parade grounds Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Fort Klamath barracks, c. 1900]()

Fort Klamath barracks, c. 1900.

Fort Klamath barracks, c. 1900 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no. 70372

-

![Fort Klamath, Modoc gravesite, 1894]()

Fort Klamath, Modoc gravesite, 1894.

Fort Klamath, Modoc gravesite, 1894 Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-USZ6

-

![Fort Klamath cavalry, 1868]()

Fort Klamath cavalry, 1868.

Fort Klamath cavalry, 1868 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi56238

Related Entries

-

![Kintpuash (Captain Jack) (c. 1837-1873)]()

Kintpuash (Captain Jack) (c. 1837-1873)

Kintpuash (Strikes the Water Brashly), also known as Captain Jack an…

-

![Modoc War]()

Modoc War

The Modoc War, waged mostly over the winter and spring of 1872-1873, th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Murray, Keith A. The Modocs and their War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Riddle, Jeff C. The Indian History of the Modoc War. San Jose, Calif.: Orion Press, 1998.

Ron Field. Forts of the American Frontier 1776-1891: California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2011.

Utley, Robert M. Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indians, 1866-1891. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1973.