Before Stonewall

Before New York’s Stonewall Riots in 1969, the history of gay rights in Oregon, as in the United States generally, was one of curtailment. For example, in the nineteenth century when Oregon formed as a territory and then a state, lawmakers adopted a statute criminalizing sodomy, whether consensual or not. In response to a major homosexual scandal that gripped Portland at the end of 1912, the state legislature strengthened the sodomy law in 1913, extending its maximum sentence in the penitentiary from five to fifteen years and expanding the definition of what constituted an act of sodomy. In addition, from early in the twentieth century into the 1970s, local law enforcement officials persistently used nuisance ordinances to harass and prosecute people who patronized gay bars.

Beginning in the 1950s, gays in a few places in the United States began to push back against such laws and prejudice and to demand better treatment. This period, extending to the end of the 1960s, is generally known as the "Homophile" era, during which a few social and rights groups, such as the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, formed first in Los Angeles and San Francisco, with chapters then spreading to a few other major cities. Seattle gays, for example, created their first homophile group in 1967. Through this period, however, no similar effort occurred in any Oregon city, though in the winter of 1964-1965, gay bar owners in Portland hired attorneys to help them successfully wage a defense against city officials who wished to shut down their businesses.

Gay Liberation

New York's Stonewall event, when gays for the first time in American history violently fought back against police harassment, radicalized a new generation of gay men and lesbians. Many of these people already had participated in civil rights activities, the anti-Vietnam War protests, campus unrest, and the women's rights movement in the 1960s. This newly inaugurated "Gay Liberation" cause, as it was called, finally energized gays in Oregon.

Gays first began organizing in Portland in early March 1970. They advertised their cause in the pages of The Willamette Bridge, a counter-culture newspaper that began in 1968 and carried news about Vietnam, the Black Panthers, Students for a Democratic Society, rock concerts, alternative lifestyles, and the environment. Although the social element was important to these early activists, they immediately identified politics as central to their purpose. They outlined a plan to speak in college classes and to church and civil groups, to provide radio and television interviews, to write articles for the press, and to lobby for the abolition of legislation that oppressed gays. Gay Liberation in Portland also led to the formation of local organizations such as the Second Foundation, which on May 7, 1972, opened the first gay community center in Oregon.

Also in the early 1970s, young activists in Eugene, Corvallis, and Klamath Falls joined their Portland counterparts to organize and begin working toward the acceptance and the expansion and protection of civil rights in their communities and in the state. Over the years, the cause was at times halting as the gay movement also experienced setbacks, backlash, and defeats.

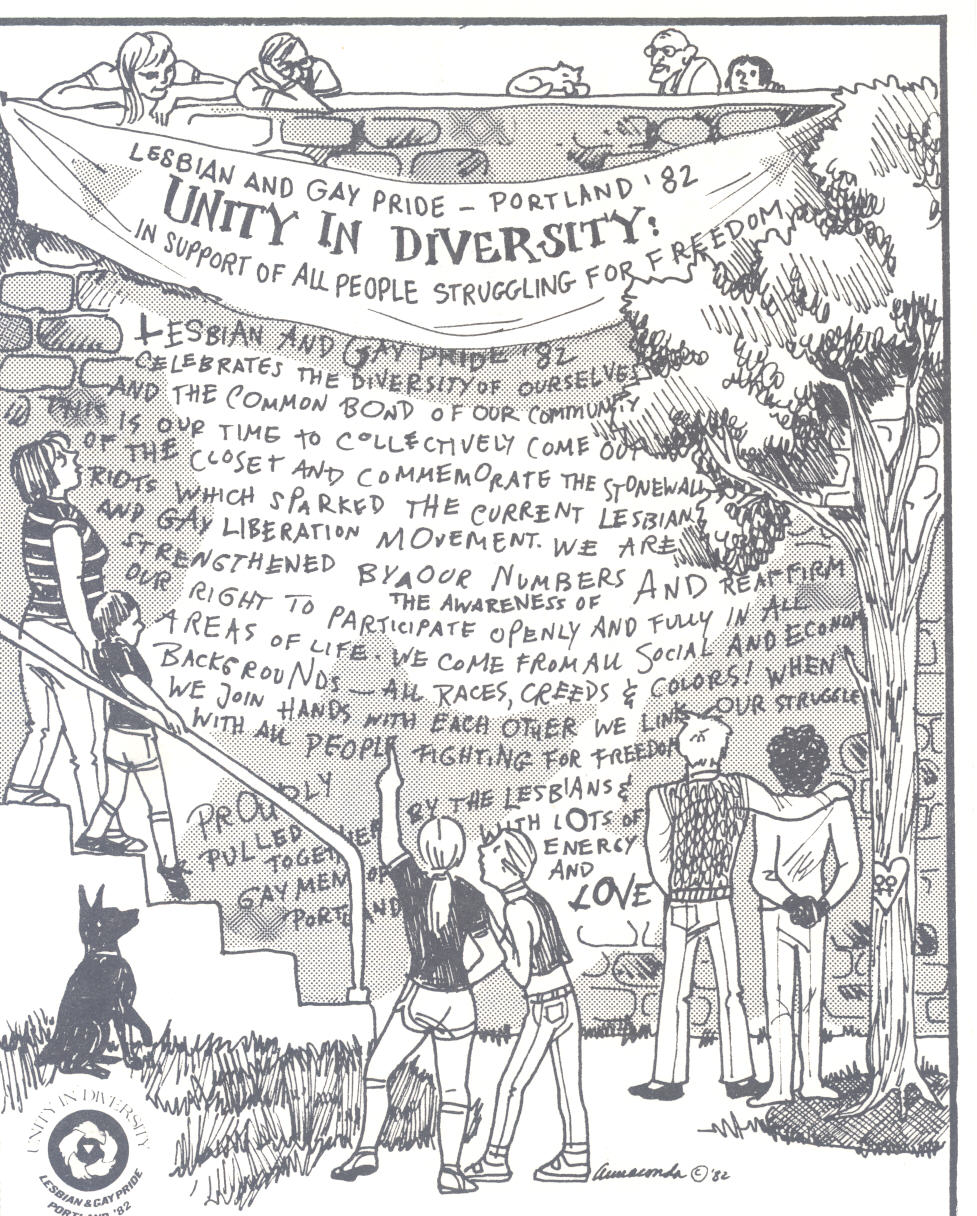

In general, advancement came as the HIV/AIDS epidemic brought greater awareness to gay issues, as allies to the movement gained courage, and as lesbian and gay people became more visible. For example, Oregon’s first gay newspaper, The Fountain, began publishing in 1971, the same year Portland hosted the state’s first gay pride celebration. The next year, Lanny Swerdlow began hosting a local half-hour program about gay issues on Portland’s KBOO Radio. Even the conservative backlash against gays, which began in the 1970s and reached new heights in the 1990s, moved gay rights forward, causing those involved in the movement to become better organized and attracting larger numbers of heterosexuals to the cause.

Successes and Setbacks, 1970s

The first major gay rights victory in Oregon was the legislative repeal of the sodomy law on July 2, 1971, which took effect on January 1, 1972. The repeal was due less to activists than it was part of a general reform of criminal codes taking place at the state level across the nation. In fact, when the legislature in neighboring Idaho realized it had rescinded its sodomy law in 1971 through a general repeal of old common-law crimes, it quickly re-adopted it. Only in 2003 did the U.S. Supreme Court finally strike down the last sodomy laws still remaining on the books in a few states.

Portland was the first city in Oregon to adopt civil rights protections for gays and lesbians. The December 1974 ordinance, championed by Commissioner Connie McCready, banned anti-gay discrimination in municipal employment. A bold step in the national context, Portland nevertheless lagged behind Seattle, which in 1973 adopted a bill that protected gays in employment and housing in that city. Portland would not adopt such expansive safeguards until 1991.

Eugene began hearings on gay rights in 1972 and adopted an ordinance similar to Seattle’s in 1977. By then, a conservative backlash had ignited across the country, part of a general reaction against the perceived moral decline of the 1960s and partly a strengthening of the religious right in America, a group that would become a force in national politics over the next decades. Energized by activist Anita Bryant’s successful 1977 campaign to repeal a gay rights law in Dade County, Florida, conservatives in Eugene revoked its ordinance in a referendum the following year. Wichita, Kansas, and St. Paul, Minnesota, also repealed gay rights that year, although voters in Seattle held off a similar referendum.

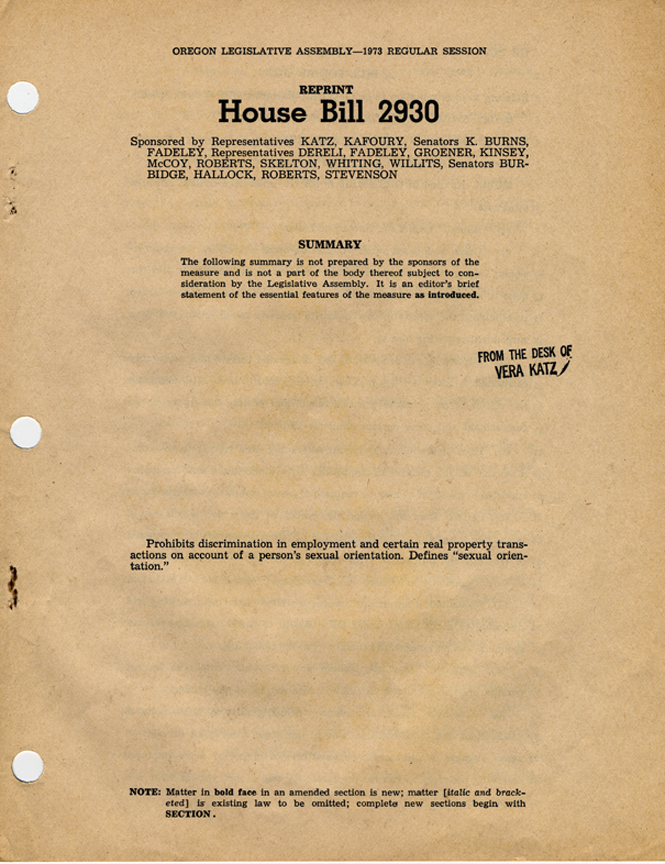

In 1973, Portland and Eugene gay activists worked with state representatives Vera Katz and Steven Kafoury, both from Portland, to introduce a gay rights bill in the Oregon legislature. Although the bill received more "yes" than "no" votes in the House, it failed to garner enough to send it on to the Senate, and thus failed. Various versions of the bill appeared in six of the next seven biennial sessions, each bill going down to defeat. Through these years, the Portland Town Council, a gay rights group that formed in 1975, worked tirelessly on these and other efforts.

As activism across the nation met with such defeats in the 1970s and as the conflicts that invariably arise in any civil rights movement occurred, a number of lesbians and gays, grown weary from dashed hopes and slow progress, began to retire from the field. Southern Oregon became particularly attractive to them, especially lesbians, where they found reasonably inexpensive land. There they formed a number of intentional communes and collectives—among them, Oregon Women's Land Trust, Fly Away Home, and the gay men's Nomenus. In these communities, retired activists along with others who lived an alternative lifestyle worked to achieve the equality and social bonds they had been unable to realize in mainstream America.

In the 1980s, a number of these back-to-the-landers would be drawn back into gay politics as a conservative backlash intensified, especially in rural Oregon. Lesbians from Trillium Valley Farm, for example, would be instrumental in the 1980 creation of Roseburg's Gay and Lesbian Alliance.

Although Governor Robert Straub had appointed a task force to study the status of gays in Oregon in 1977, the more important changes for the state's expectant sexual minorities would not begin for another decade. In 1987, after the legislature again refused modest protections for gays, Governor Neil Goldschmidt signed an executive order prohibiting discrimination against gays in state employment.

Conservative Backlash, 1980s & 1990s

Tensions ran high. The conservative movement had gained enough momentum in the 1980s that Oregon’s Republican Party chairman felt comfortable enough to make negative statements about connections between gay rights and Governor Goldschmidt. Soon Josephine County voters circulated an initiative that would quarantine people in the county infected with HIV/AIDS.

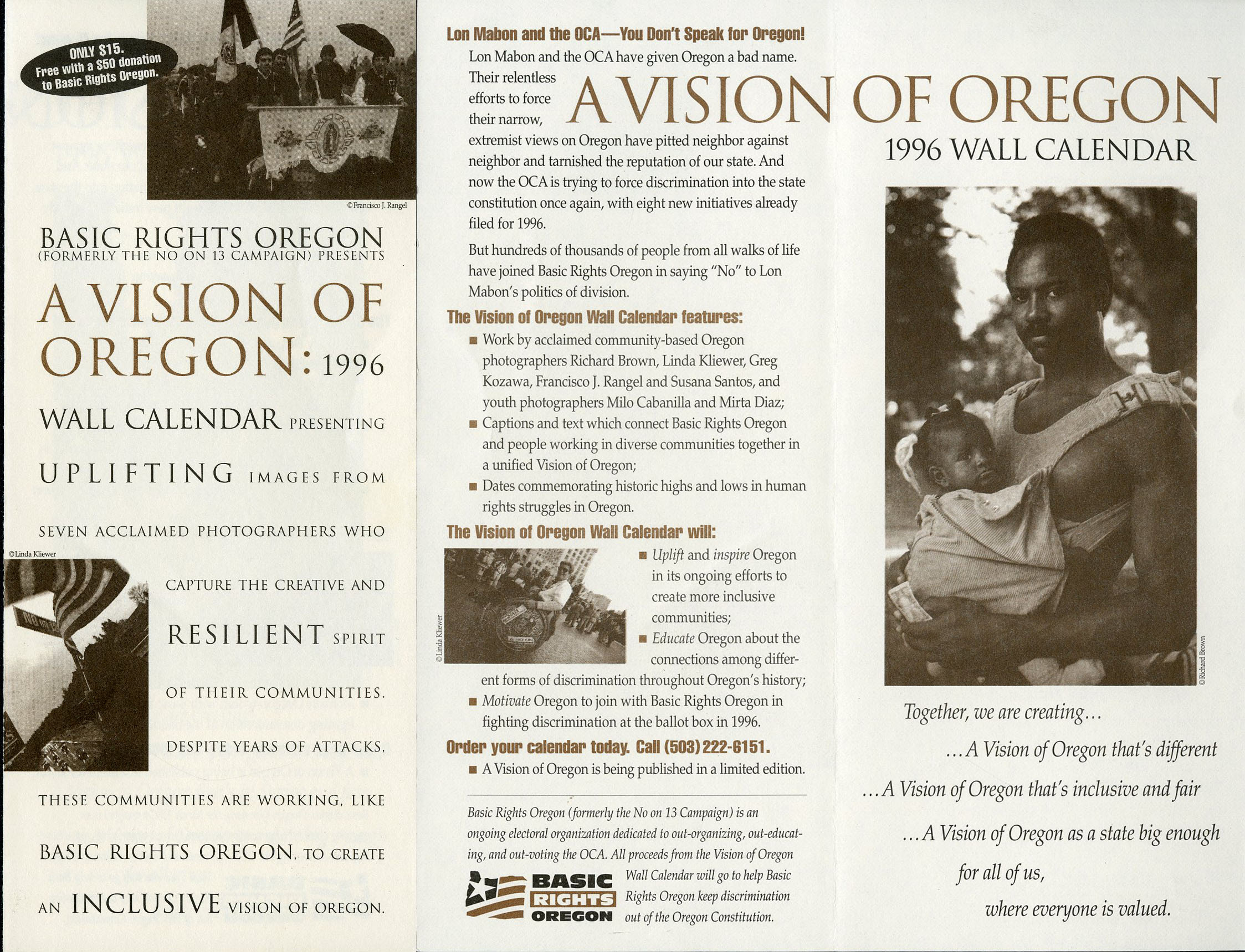

In that atmosphere, the Oregon Citizens Alliance (OCA), a conservative political group founded in 1986 and led by activist Lon Mabon, placed a referendum on the 1987 November ballot that succeeded in repealing Goldschmidt’s order. Emboldened, the OCA expanded its efforts, sponsoring fiercely contested statewide ballot measures in 1992 and 1994. The ballot measures were attempts to curtail gay rights, to require the state to take anti-gay stands, and to forbid state and local governments from passing anti-discrimination laws. Both OCA measures were defeated, in part due to a strong urban vote against them.

Many voters in rural Oregon felt differently, which led the OCA to soon achieve anti-gay rights laws in twenty-seven cities and counties in the state. Gail Shibley, Oregon's first openly lesbian or gay legislator (first appointed in 1991) worked with others in the 1993 Oregon legislature to pass a state law prohibiting local communities from enforcing discriminatory ordinances. This, plus a 1996 U.S. Supreme Court decision that knocked down an anti-gay constitutional amendment in Colorado, hamstrung the OCA campaign at the local level.

Still riding a wave of popularity in the early 1990s, however, the OCA sponsored anti-gay rights campaigns in the neighboring states of Washington and Idaho. Gay rights supporters quickly formed "Hands Off Washington," which successfully ended OCA efforts there. In Idaho, however, OCA members formed the Idaho Citizens Alliance. It succeeded in placing a measure similar to Measure 9 on the Idaho ballot in 1994. The measure failed, but only by the narrowest of margins.

The Marriage Issue

In 1993, amid all this conservative backlash, Hawaiian courts determined that there was no compelling reason why that state should not extend marriage rights to gays. Overnight, gay rights supporters and detractors found themselves pitted against each other over the issue of marriage. The federal government adopted the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996, disallowing federal benefits to gays where they might marry and making it possible for states to refuse to recognize marriages between members of the same sex, even if they took place in states where it was legal. By 2010, forty-one states had adopted laws or constitutional amendments preventing gays from marrying; only five states and the District of Columbia allowed it.

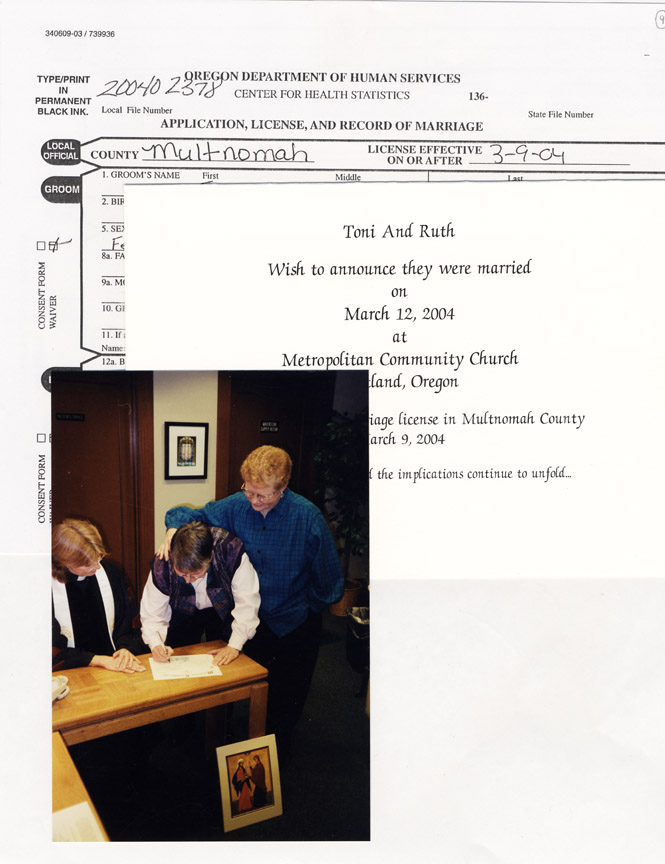

In 2004, the Multnomah County attorney determined that the state's constitution prohibited counties from discriminating against same-sex couples in marriage license applications. The chair of the county's Board of Commissioners then ordered the issuance of licenses to gay applicants, and some 2,000 couples signed up. Later that year, however, Oregon voters passed Ballot Measure 36, which constitutionally defined marriage in Oregon as a union between a man and a woman.

In 2005, the Oregon Supreme Court declared the Multnomah County gay marriages void. Two years later, Governor Ted Kulongoski signed a domestic partner bill that provides gay couples who register as domestic partners many of the rights (though none of the federal benefits) that married couples in Oregon receive.

Expanding Rights and Marriage in the 2000s

At the state level, hate crime laws were passed to protect gay, lesbian, as well as transgendered people in 1989, 2001, and 2007. In 2007, they received freedom from discrimination rights in state-supported schools, and they were permitted to adopt children. Over those years, more urban and liberal municipalities—including Salem, Eugene, Lincoln City, Ashland, Corvallis, and Bend—would also adopt gay rights ordinances.

The marriage issue continued to preoccupy lawmakers, the general public, and more and more LGBT people in the years after Oregon’s domestic partner law of 2007, in part because of lawsuits brought by same-sex couples within the state and because of developments in other states where defense of marriage acts were beginning to be repealed. In response to some other states allowing same-sex marriage by 2013, Oregon began recognizing such unions within its boundaries, even though same-sex marriages could still not legally be conducted within the state. Most important for expanding marriage rights in Oregon were U.S. Supreme Court rulings in 2013, U.S. v. Windsor, and in 2015, Obergefell v. Hodges. Obergefell v. Hodges determined that state bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. As a result, same-sex marriage became legal in Oregon on January 1, 2016.

Since 1970, Oregon’s lesbians and gays have seen their civil rights and protections expand considerably, yet the realization of those rights has included setbacks and controversy. Also, there are still laws in the Oregon constitution that exist specifically to curtail equality for sexual minorities. The story of gay rights in Oregon is still an evolving one.

-

![House Bill 2930, sponsored by Vera Katz among others, prohibited discrimination in employment based on sexual orientation.]()

House Bill 2930, 1973.

House Bill 2930, sponsored by Vera Katz among others, prohibited discrimination in employment based on sexual orientation. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, ba0186372

-

![]()

Lesbian and Gay Pride, Portland, 1982.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, GLAPN Coll., Mss2988-2

-

![]()

Multnomah County marriage license, announcement, and photograph, 2004.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bc0065943

-

![]()

Pride Month, governor's proclamation, 2014.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, GLAPN Coll., Mss2988-1

-

![]()

Gay Pride Parade, Portland, 1987.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, GLAPN Coll., Mss2988-1

-

![]()

Gay Pride Parade, Portland, 1987.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, GLAPN Coll., Mss2988-1

Related Entries

-

![Basic Rights Oregon]()

Basic Rights Oregon

Established in 1996, Basic Rights Oregon is a statewide political organ…

-

![Oregon Queer History Collective (Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest)]()

Oregon Queer History Collective (Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest)

The Oregon Queer History Collective, formerly known as the Gay & Lesbi…

-

![Portland Gay Men's Chorus]()

Portland Gay Men's Chorus

The Portland Gay Men's Chorus (PGMC) was founded in April 1980 to perfo…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boag, Peter. "‘Does Portland Need a Homophile Society?’ Gay and Lesbian Culture and Political Activism in the Rose City from World War II to Stonewall." Oregon Historical Quarterly 105:1 (Spring 2004): 6-39.

Boag, Peter. Same-Sex Affairs: Constructing and Controlling Homosexuality in the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Kleiner, Catherine. "Nature's Lovers: The Erotics of Lesbian Land Communities in Oregon, 1974-1984." In Seeing Nature through Gender, Virginia J. Scharff, ed., pp. 242-262. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

Marcus, Eric. Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal Rights. New York: Perennial, 2002.

Stein, Arlene. The Stranger Next Door: The Story of a Small Community’s Battle over Sex, Faith, and Civil Rights. Boston: Beacon Press, 2002.