The Great Plank Road, constructed in 1856, connected productive agricultural communities in the Tualatin Valley to Portland. Paved with sixteen-foot, three-inch-thick wooden planks, the road offered an improved route from agricultural communities to Portland and its large market. Before the road's construction, Tualatin farmers used Canyon Road, surfaced with rock and dirt and often nearly impassable in adverse weather conditions. Perhaps more important, planked roads allowed farmers to haul larger loads and at greater speed.

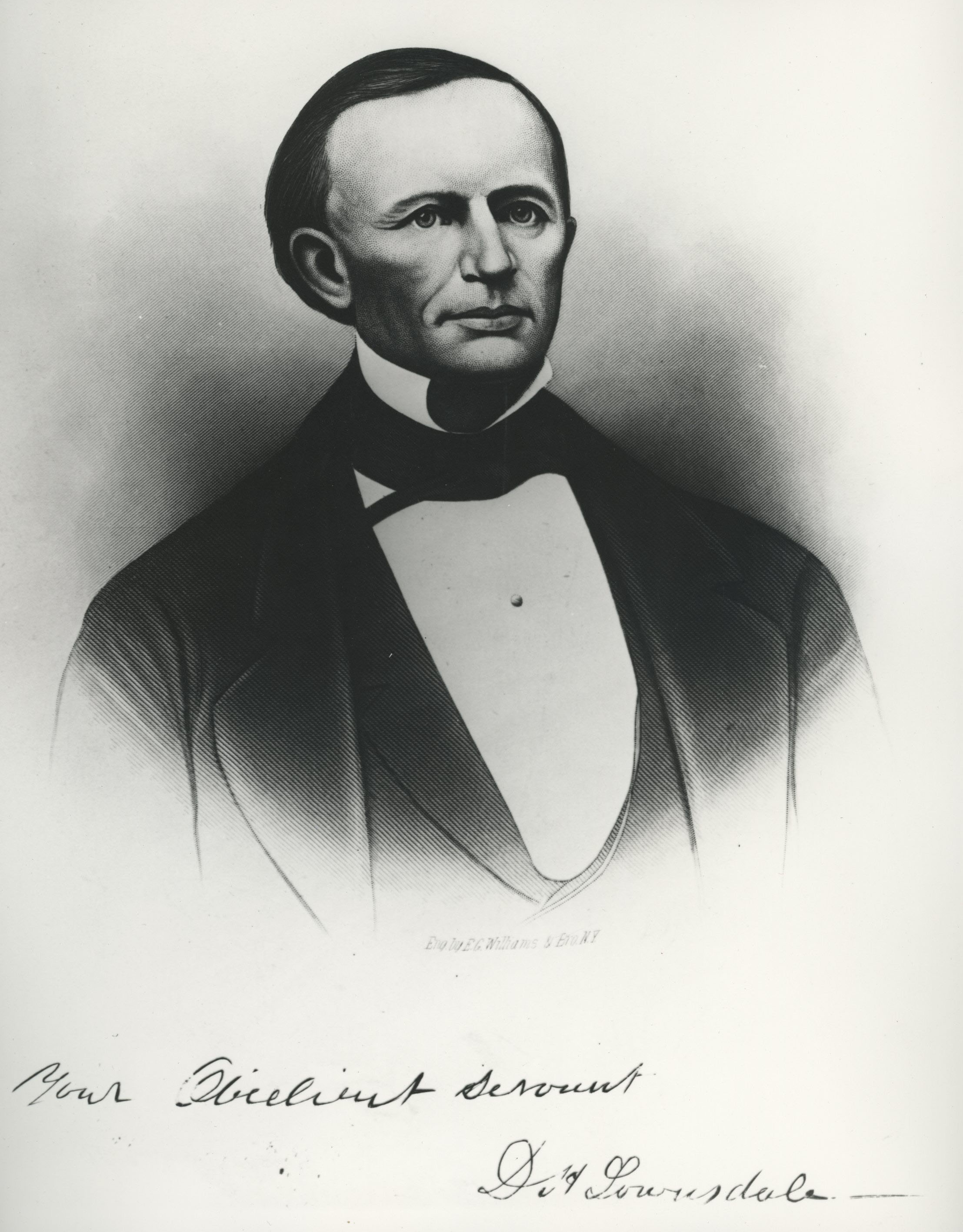

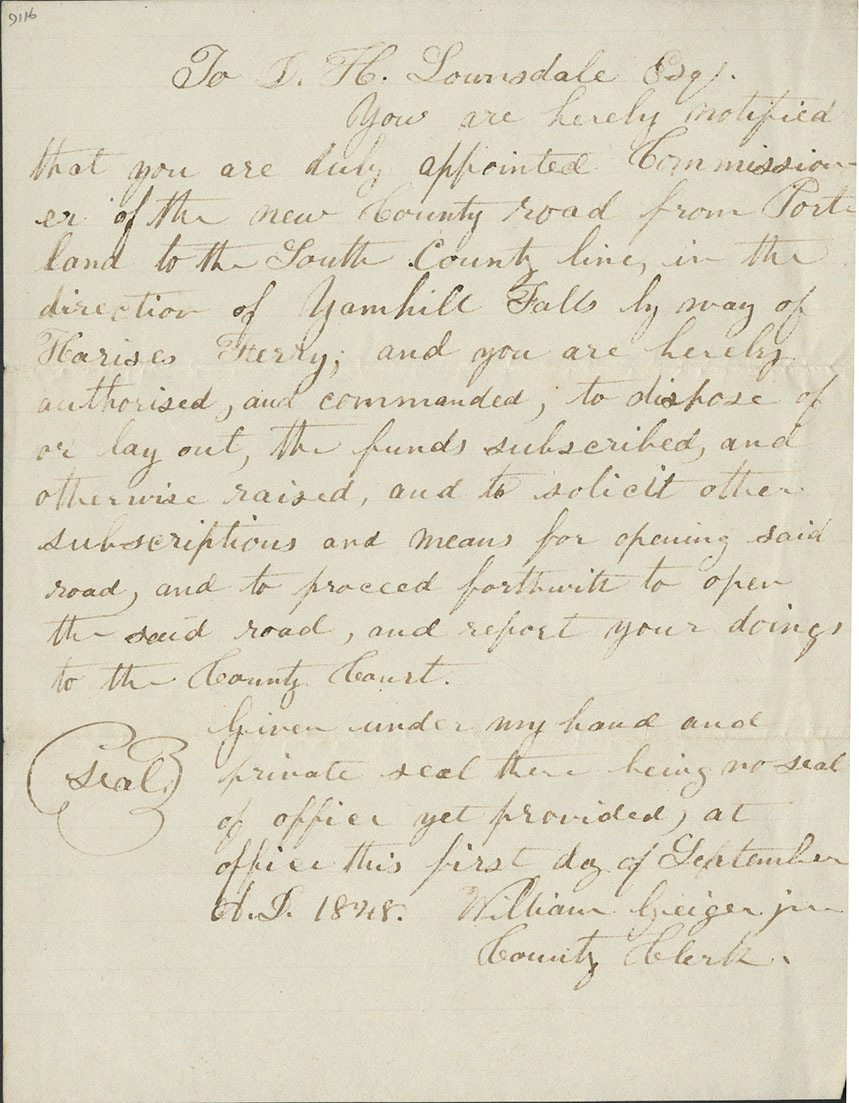

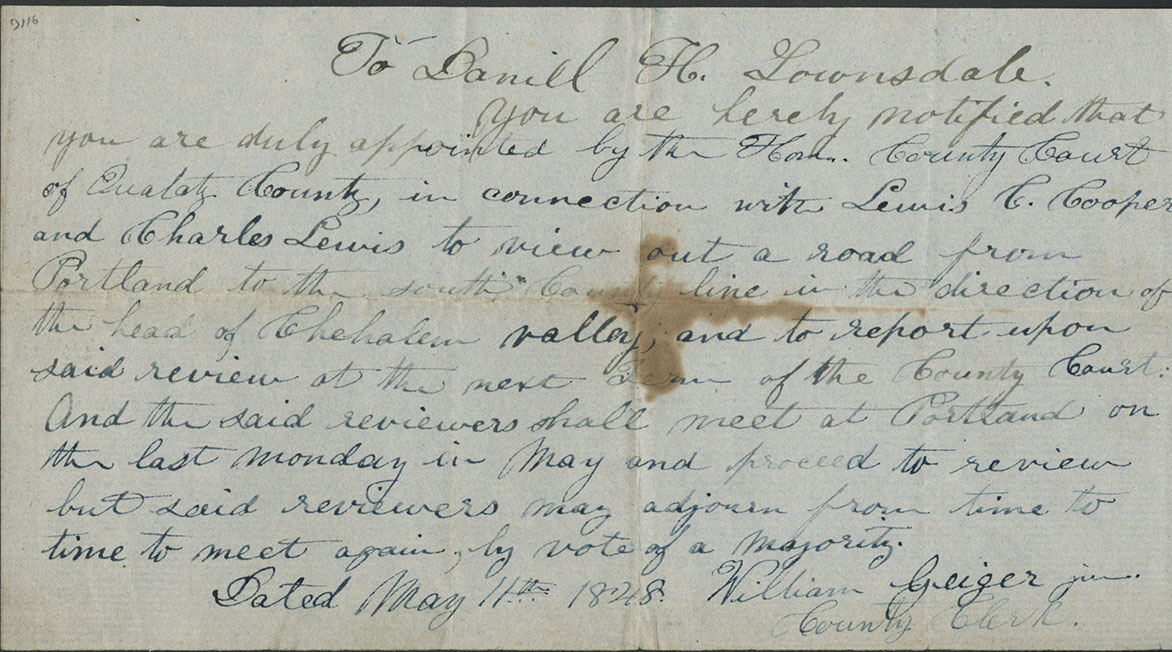

The idea for the road came from Daniel Lownsdale, a Portland tannery operator, who in 1852 donated land to the city that became the South Park Blocks. In 1849, he had scouted the road’s route from Lafayette in the Yamhill Valley to Portland. Along with partners Stephen Coffin and William Chapman, Lownsdale petitioned the Oregon territorial legislature for a charter; he received approval in August 1851. Thomas Dryer, editor of the Oregonian, gave his support to the project, and directors of the Portland & Valley Plank Road Company advertised for stockholders and a hundred workers to begin construction.

According to historian Carl Abbott, "Plank roads had spread widely through the eastern United States and Canada in the 1840s and early 1850s because of their low cost compared to railroads. Construction was simple. Relatively light 'sleepers' or 'stringers' were laid along the route of the road in two parallel rows about four feet apart. Planks, eight feet long and three or four inches thick, were laid across the stringers and spiked into place (if spikes were scarce, they could be held in place by dirt piled at each end). Experts recommended that a dirt track parallel the planked road to serve as a turnout and passing lane. In their enthusiasm for these 'farmers’ railroads,' promoters ignored the problems of fragile construction and decay. Most plank roads lasted only a few years before deteriorating to the point of abandonment."

Coffin took on the contract for the first five-mile section, which began at the city’s western plat line. Workers laid the first planks on September 27, 1851, while citizens celebrated with a large barbecue picnic that featured political speeches, a roasted ox, and a gold coin buried beneath the first-laid plank. By early 1852, workers had laid planks up present-day Canyon Road, creating a sixteen-foot-wide roadway to accommodate single wagons, with turnouts that allowed vehicles to pass. The directors put out bids to complete the city portion of the road to Park Avenue on Jefferson Street.

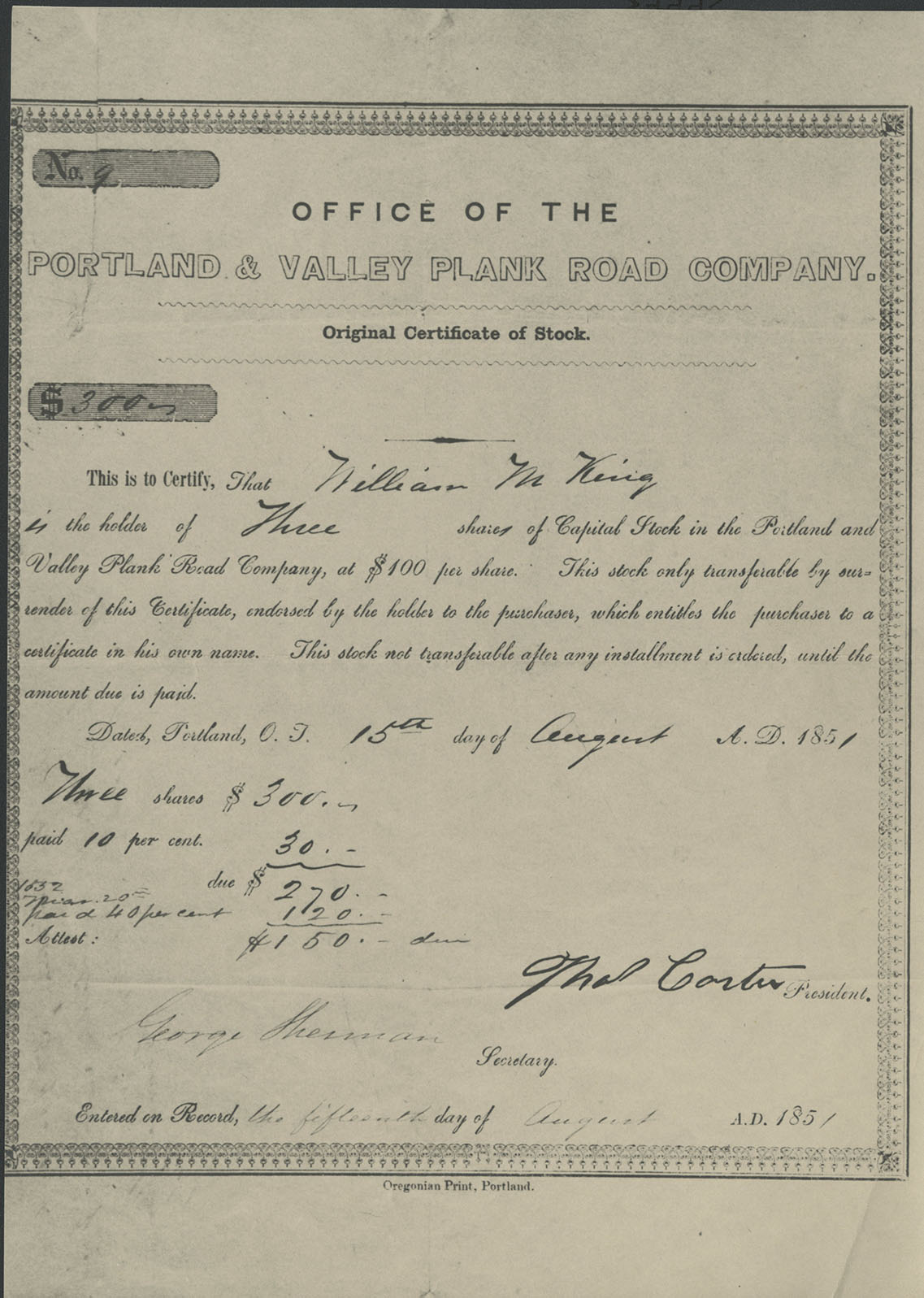

The company had spent $14,593 on construction, overseen by superintendent William M. King, but it collected only $6,026 from subscribers. In March 1852, company directors threatened to bring suit against subscribers who had not fulfilled their monetary pledges. Nearly a year later, and one month after the January 1853 charter requirement to complete ten miles of road, the company admitted that its financial records were a shambles, blaming King for mismanagement. The Portland & Valley Plank Road Company was dead.

In 1854, Washington County began sheriff sales on company materials to retrieve some value from the Great Plank Road debacle. Nonetheless, there were still compelling reasons to complete the road. W.S. Ladd and other Portland businessmen began a campaign to create a new road company, which received a territorial charter in February 1856 as the Portland and Tualatin Plains Plank Road Company. The new company began with more capital than Lownsdale’s effort and secured sufficient stockholders by June 1857 to complete construction. The tolls reveal how the company planned to make a profit: a wagon, seventy-five cents; a horse and rider, thirty-seven and a half cents; loose cattle, ten cents each; and a hog or sheep, five cents.

By 1867, the Oregonian had called for upgrading the already deteriorating road by macadamizing the surface. Five years later, the newspaper argued that plank roads were a waste of money compared to constructing railroads. The Great Plank Road had become anachronistic.

In 2010, construction workers laying tracks for the light rail system in Portland uncovered original slabs from the Great Plank Road. The MAX light rail system's Goose Hollow station commemorates the road, and present-day U.S. Highway 26 follows a portion of the original plank road route west from Portland.

-

![]()

William King's certificate of stock for share for the Plank Road Co., 1851 .

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 134

-

![]()

Fragment of the Great Plank Road, Portland, 1856.

OHS Museum, 79-38.1.1 -

![]()

D. H. Lownsdale.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 72569

-

![]()

Lownsdale's appointment as Commissioner of the Plank Road, 1848 .

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 134

-

![]()

Note authorizing Lownsdale to survey the road route, 1848.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 134

Documents

Related Entries

-

Columbia River Highway

The Columbia River Highway, now known as the Historic Columbia River Hi…

-

![Portland]()

Portland

Portland, with a 2020 population of 652,503 within its city limits and …

-

![US 101 (Oregon Coast Highway)]()

US 101 (Oregon Coast Highway)

Many places on the Oregon coast were virtually inaccessible in the earl…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Tims, Dana. "Beaverton road project unearths Oregon's history." Porland Oregonian, August 21, 2015.

Abbott, Carl. Portland in Three Centuries. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2011.

Abbott, Carl. "The Plank Road Enthusiasm in the Antebellum Middle West." Indiana Magazine of History (June 1971).