Johnson Creek is a small stream in the Portland metropolitan area which has frequently flooded and suffered from severe pollution. Since the mid-1980s, however, it has gained attention for the successful stream-restoration efforts by local advocacy groups. It is twenty-five miles long and drains fifty-four square miles. It flows from the foothills of the Cascade Mountains to its confluence with the Willamette River, just south of downtown Portland. Approximately 175,000 people live in the watershed. An industrial district on the lower watershed has contributed to the pollution of the creek.

Johnson Creek has an allure that seems out of proportion to its size. Novelist David Duncan dedicated his novel The River Why (1988) to the creek, and a feature in Doubletake magazine in 2000 gave it the dubious distinction as the “73 Chevy impala of rivers." Johnson Creek figures as a primary inanimate character in Mikal Gilmore’s prize-winning book, Shot in the Heart (1994), about his brother Gary, a serial murderer who grew up along the banks of the creek and who first learned to shoot a gun near where a storm-water agency has created a constructed wetlands.

Prior to white settlement, the creek was fished by Chinook people and other Native American groups. It was first settled by white pioneers in the 1840s and named after William Johnson, who in 1846 built a water-powered sawmill along the creek ten miles east of the confluence with the Willamette River. The lower stretch of the creek was settled in the same period.

The earliest donation land claim was by Jacob Wills in 1848. Wills built a water-powered sawmill in 1849 at about mile two, just south of Tideman Johnson Nature Park. A third mill was operated by William Meek, a partner of Lot Whitcomb’s, at the mouth of Johnson Creek. Until the early twentieth century, the creek was known as Mill Creek in the lower reach.

Since the 1920s, over forty-five studies and plans have made recommendations about how to solve Johnson Creek's flooding and pollution problems. In the 1930s, Works Progress Administration workers altered the creek's path and lined part of the creek bed with stones in an effort to prevent overflow. Their efforts are still visible in Tideman-Johnson Park. Most of the plans failed, in some cases because of flawed scientific reasoning, but more often because watershed residents resisted the changes. In the 1970s, for example, the Metropolitan Services District (MSD)1 proposed the creation of a Local Improvement District (LID). A citizen group was formed to oppose it, citing, among other things, boundary disputes, the cost of property taxes, and the issue of government jurisdiction. The citizens turned down the formation of a LID and organized under a new name, the Up the Creek Committee, to collect signatures for a petition to eliminate MSD. Although the petition failed, the citizen rancor put a damper on any attempts to remedy pollution and flooding problems.

In the mid-1980s, citizens in the watershed and environmentalists from the Portland area organized to save the creek. A group calling itself the Johnson Creek Marching Band was formed in 1984. They organized volunteer stream cleanups and lobbied government agencies to take action. This small group eventually morphed into the Friends of Johnson Creek, which played a central role in the mid-1990s in creating a multi-jurisdictional planning organization, the Johnson Creek Corridor Committee (JCCC). The JCCC, spearheaded by the City of Portland's Bureau of Environmental Services, had representatives from multiple jurisdictions and government agencies as well as citizens representing reaches of the stream. In 2001, the JCCC was renamed the Johnson Creek Watershed Council and incorporated as a separate nonprofit organization.

While the creek still floods and is polluted, the outpouring of support from citizens and government agencies working together has been dramatic. Between 1990 and 2002, there were over 1,000 watershed events: public input meetings, watershed council meetings, restoration projects, tours, workshops, and cleanups. During this period, there were up to 8,000 citizens involved in helping to restore the stream.

There are some indicators that the stream is slowly recovering. An exhaustive stream survey in 2006 of a 1,000-foot stretch of the creek revealed over 1,000 fish specimens, including over 100 native salmon and, most surprising, no invasive fish species.

The Johnson Creek Watershed Council provides opportunities for citizens to be involved in continuing cleanup and restoration efforts. The City of Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services’ Watershed Management Program oversees the health of the stream, acquires land in the flood plan, and develops large-scale restoration projects.

-

![Johnson Creek, postcard]()

Johnson Creek, postcard.

Johnson Creek, postcard Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no.54180

-

![Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1931]()

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1931.

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1931 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., City of Portland, COP2933

-

![Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1931]()

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1931.

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1931 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., City of Portland, COP2927

-

![Johnson Creek, Civil Works Admin. project, 1933]()

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1933.

Johnson Creek, Civil Works Admin. project, 1933 Courtesy Oreg, Hist. Soc. Research Lib., City of Portland, COP03088

-

![Johnson Creek, 1934]()

Johnson Creek, 1934.

Johnson Creek, 1934 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, City of Portland, COP03184

-

![Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1934]()

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1934.

Johnson Creek, CWA project, 1934 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., City of Portland, COP09089

-

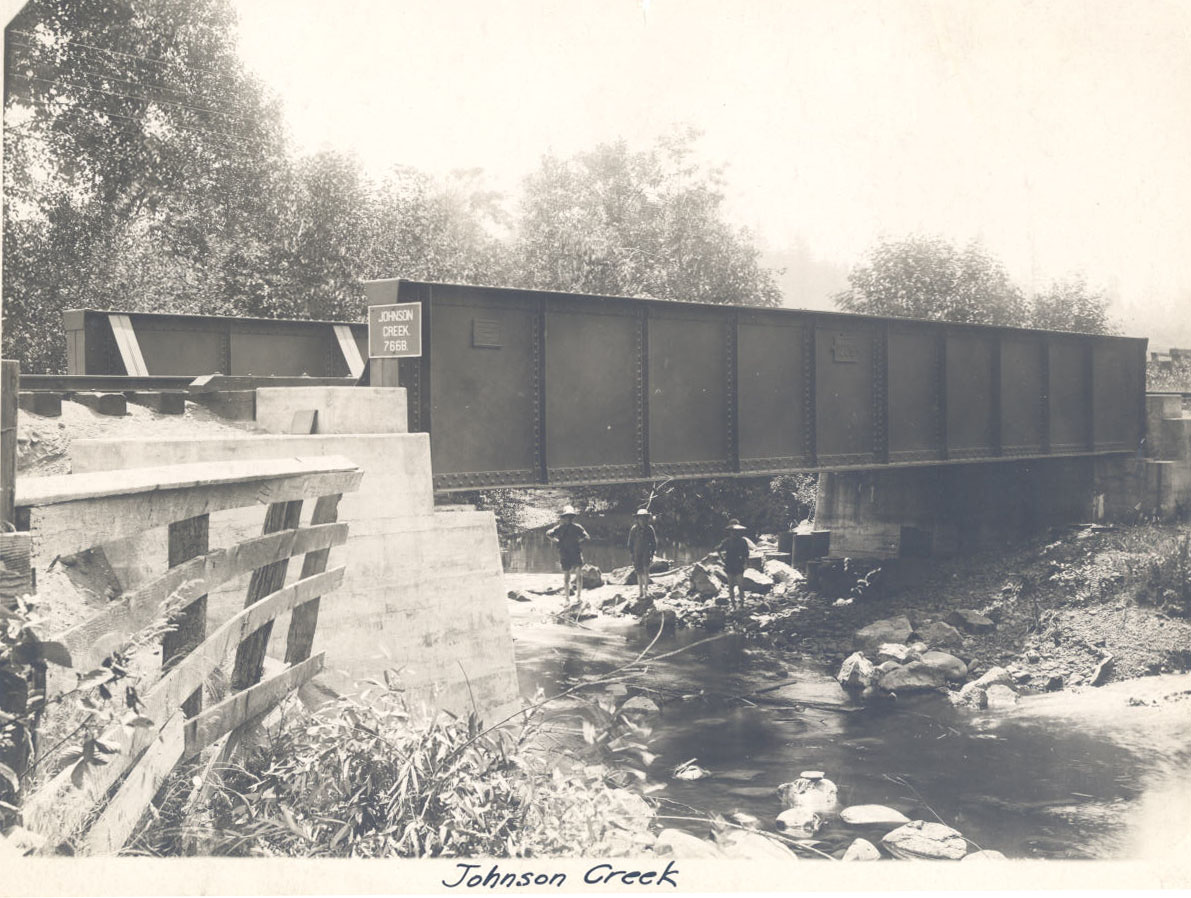

![Johnson Creek, S&P bridge]()

Johnson Creek, S&P bridge.

Johnson Creek, S&P bridge Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., S&P collection, OrHi76286

-

![Interurban trestle over Johnson Creek, 1956]()

Interurban trestle over Johnson Creek, 1956.

Interurban trestle over Johnson Creek, 1956 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 010596

-

![Johnson Creek floods SE Foster, 1962]()

Johnson Creek floods SE Foster, 1962.

Johnson Creek floods SE Foster, 1962 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi187687

-

![Johnson Creek before dredging, 1966]()

Johnson Creek before dredging, 1966.

Johnson Creek before dredging, 1966 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Johnson Creek flooding SE 104th and Yukon, 1966]()

Johnson Creek flooding SE 104th, 1966.

Johnson Creek flooding SE 104th and Yukon, 1966 Courtesy Oreg, Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi87689

-

![Johnson Creek, high water, 1982]()

Johnson Creek, high water, 1982.

Johnson Creek, high water, 1982 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

Related Entries

-

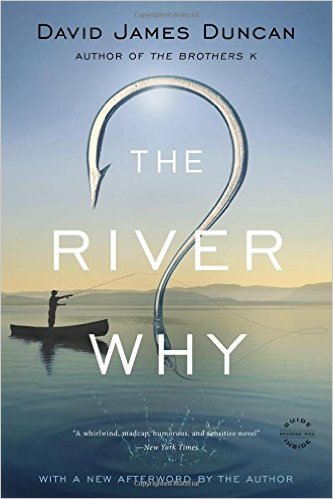

![David James Duncan (1952-)]()

David James Duncan (1952-)

Rivers have always fascinated Oregon author David James Duncan, who was…

-

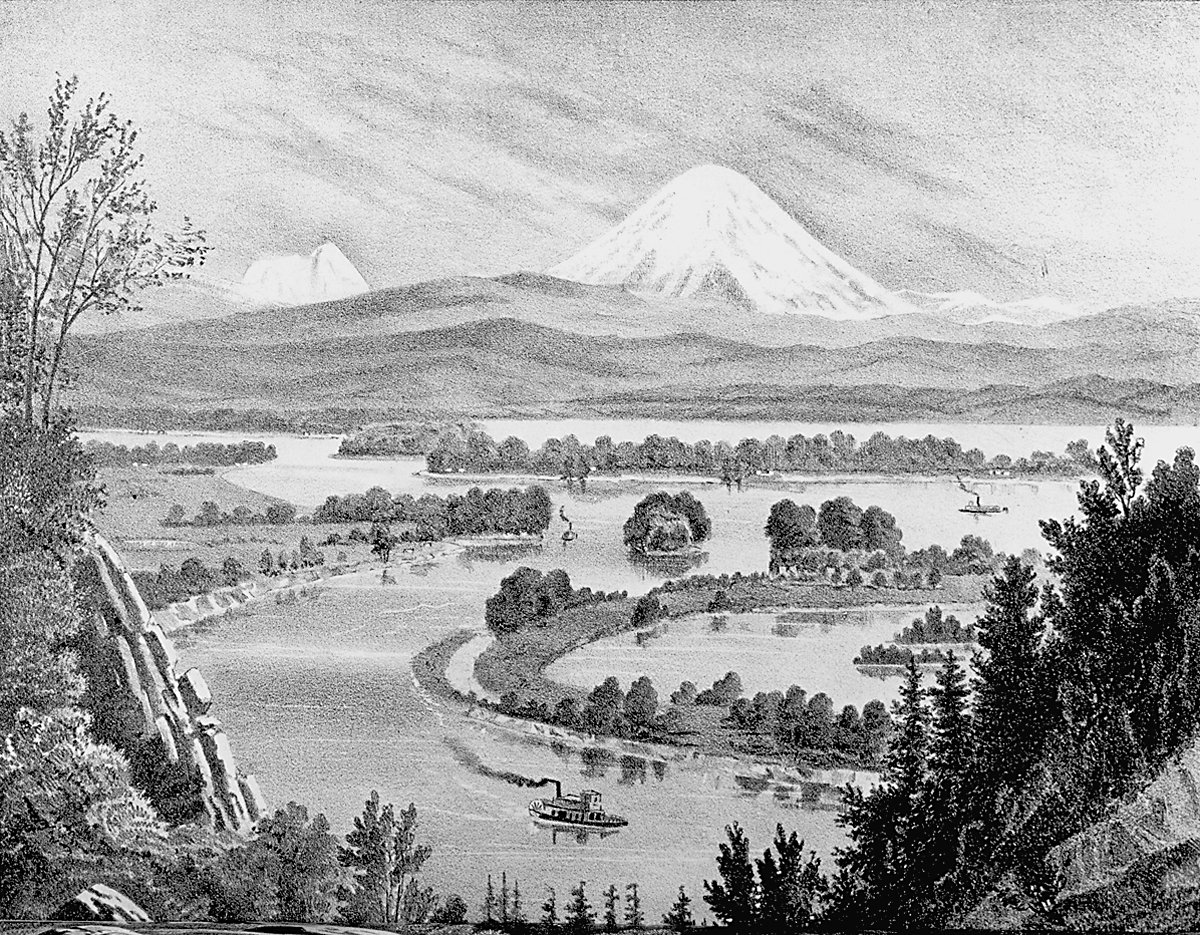

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"Johnson Creek." City of Portland, Bureau of Environmental Services, Watershed Management Program. http://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/32201

Hottman, Sara. "East Lents Floodplain Project wraps up, creates 70-acre natural area in East Portland." Oregonian, December 27, 2012. http://www.oregonlive.com/gresham/index.ssf/2012/12/east_lents_floodplain_project.html

Johnson Creek Watershed Council. http://www.jcwc.org/.