Charles Ray Jordan was a towering figure in Portland history. The first African American to serve on the Portland City Council, he was the director of Portland Parks and Recreation for fourteen years. “He was just a giant in this city,” former City Commissioner Mike Lindberg told the Oregonian when Jordan died in 2014. “He made contributions that helped every neighborhood, every single citizen.” Nationally, Jordan worked to include people of color in the environmental and land conservation movements through his engagement on national parks and conservation groups.

Born in Longview, Texas, on September 1, 1937, Jordan was thirteen years old when his mother moved with him and his two siblings to Agua Caliente Indian Reservation in the Coachella Valley in southern California. Standing six feet, seven inches tall, Jordan won a basketball scholarship to Gonzaga University in Spokane, where he served in the ROTC and graduated in 1961 with a bachelor of science degree in education, sociology, and philosophy.

Jordan spent most of the next ten years in California, working for the city of Palm Springs as recreation supervisor—the first African American to hold that post—then as Youth Outpost Director of Riverside County’s Economic Opportunity Board, responsible for youth programs in the county. During 1962–1964, he served in Germany in the U.S. Army and was honorably discharged as a first lieutenant. He also did graduate work in education at Loma Linda University and in public administration at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and was recruited in 1968 to serve as assistant to the city manager of Palm Springs. In Riverside, Jordan met Esther Gauff in 1967; they married and had two children.

In 1970, Jordan moved to Portland to head its Model Cities Program. In consultation with the neighborhoods served, the program paid for rehabilitating 1,600 housing units and planting over 600 trees. In 1972, Mayor Neil Goldschmidt tapped Jordan to be director of the city’s new Bureau of Human Services. He left the job in January 1973 to be director of the Division of Career Education Programs at the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

In 1974, Mayor Goldschmidt engineered Jordan’s appointment to fill a city council seat vacated by Lloyd Anderson, who resigned to become director of the Port of Portland. That November, Jordan was elected to the position. He finished Anderson’s term and was re-elected to four-year terms in 1976 and 1980, handily beating challengers.

As city commissioner, Jordan was known for his innovative and unconventional approaches to problem solving, first in his assignment to the Fire Bureau and the Human Resources Bureau and then to the Police Bureau. He advocated for a new veterans hospital near Emmanuel Hospital, on the east side of the Willamette River, to give an economic boost to those neighborhoods, and developed a training program to recruit people of color to the Fire Bureau.

Commissioner Jordan was assigned to head the Police Bureau in 1977. He believed that “the role of Portland’s police is to protect, but also to serve, all of the people of this community,” and he supported civilian oversight of the bureau. He also encouraged police-citizen cooperation in the city’s neighborhoods and pursued affirmative action in hiring and promotion. In March 1981, he had to deal with two off-duty officers who dumped dead possums outside a Black-owned northeast Portland restaurant, an incident that many considered threatening and racist. When Jordan and Chief Bruce Baker fired the officers, the Portland Police Association delivered a no-confidence vote for the two men. Baker resigned, and Mayor Frank Ivancie took the Police Bureau away from Jordan and assigned him to the Parks Bureau.

Resigning his City Council seat in 1984, Jordan left Portland to run the parks department in Austin, Texas. Five years later, City Commissioner Mike Lindberg, who was in charge of the Portland Parks Bureau, hired Jordan as director of Portland Parks. During his fourteen years in that office, Jordan oversaw the creation of forty-four new parks, natural areas, and community centers, including Pioneer Courthouse Square, the Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center, Delta Park, and the Southwest Community Center. He also instituted higher fees at Portland's public golf courses, which paid for hundreds of inner-city young people to visit museums, attend cultural events, and go to summer camp. In 1994, he campaigned for a $58.8 million general obligation bond measure, which over the next five years provided funding for projects in ninety-six parks around the city. In 2002, with his active support, voters approved a $10 million levy for Portland parks.

Jordan created several public-private partnerships for park improvements and programs. In 1992, the city opened its first public indoor skateboard park, a partnership between Cal Skate & Sport Store and the Bureau of Parks and Recreation. The St. Johns Community Center in north Portland offered youth programs through a partnership with the Boys and Girls Clubs of Metropolitan Portland, the Portland Bureau of Parks and Recreation, the Portland School District, and Multnomah County. And with a partnership with Nike in 2002, more than ninety outdoor basketball courts were resurfaced in more than thirty city parks.

Jordan believed that “parks are more than just fun and games. Parks build community. They connect people to people, people to neighborhoods and people to land.” He also appreciated his unique position. “What I do across the country,” he said, “no other black director can do, in terms of the tables I sit at and the audience which I address and the appointments I get. They never appoint more than one. And because I am that one…that puts a lot of pressure on. And I think it's a lot of pressure on any black man who's honest and candid with himself, if he functions in Oregon.”

The tables at which Jordan sat included the National Recreation and Parks Association, where he served on the Board of Trustees in 1984 and remained a trustee through 1989. He also was on President Ronald Reagan’s Commission on Americans Outdoors (1985), prioritizing urban parks and the people who used them. Beginning in 1988, Jordan served on the board of The Conservation Fund, a nonprofit based in Arlington, Virginia, that works on national environmental issues. He was chair of the board from 2003 to 2008 and established a land trust for Black farmers in North Carolina. "One of my missions,” he told the Oregonian in 2002, “is to color-coordinate the environmental movement to help the people of America understand that people of color love the land."

The Portland City Council renamed University Park Community Center for him in 2012. Jordan died in Portland on April 4, 2014.

-

![Commissioner (1974-1984)]()

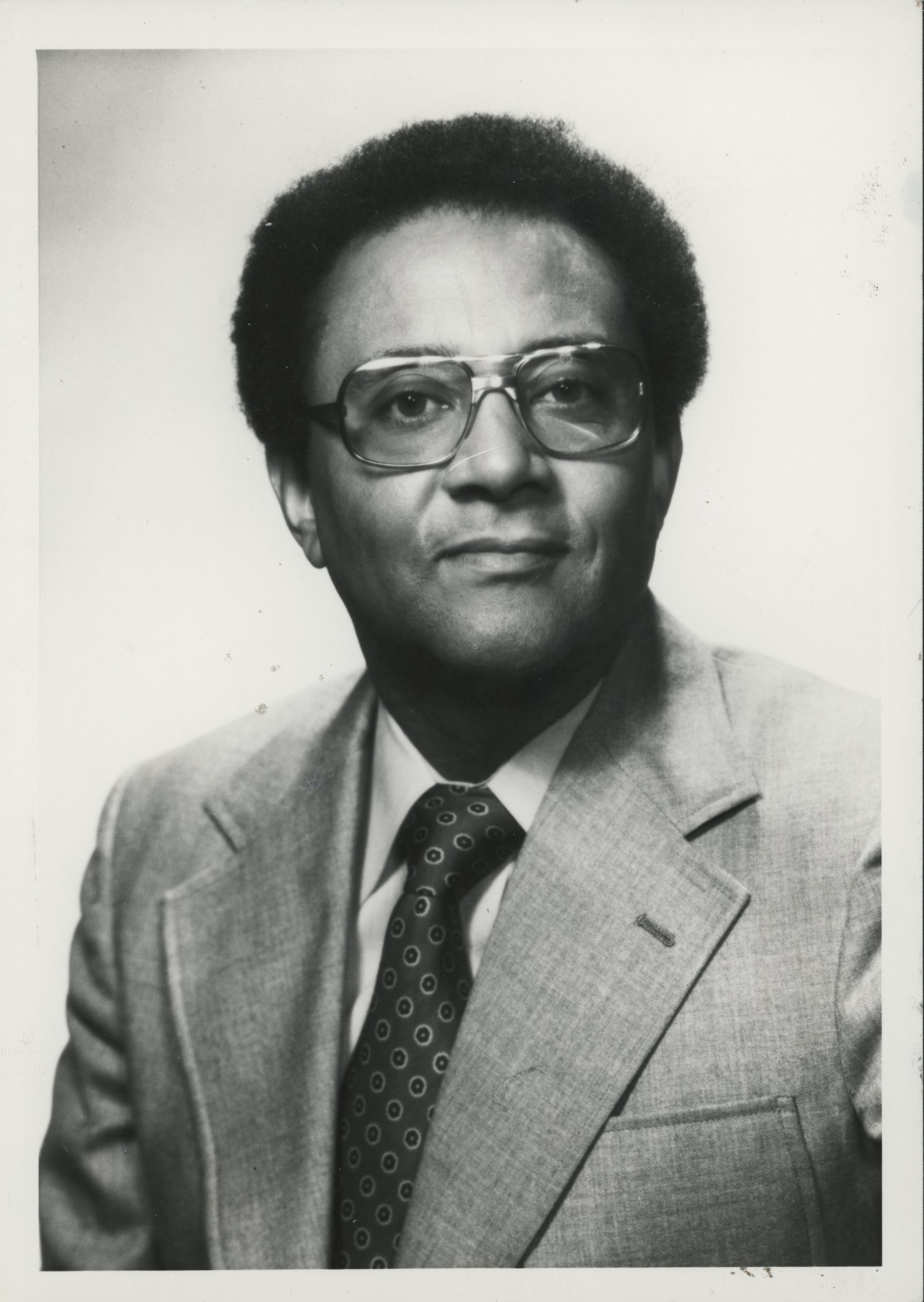

Charles Jordan, 1976.

Commissioner (1974-1984) Courtesy City of Portland, A2001-081

-

![]()

Charles Jordan.

Courtesy Portland Parks Foundation -

![]()

Charles Jordan.

Courtesy Portland Parks Foundation -

![]()

-

![]()

Charles Jordan with a group, 1975.

Courtesy Portland City Archives, Vintage Portland, A2012-005 -

![]()

Charles Jordan Community Center, Portland.

Courtesy City of Portland

Related Entries

-

![Avel Gordly (1947-)]()

Avel Gordly (1947-)

In 1996, Avel Louise Gordly became the first African American woman to …

-

![Neil Goldschmidt (1940-2024)]()

Neil Goldschmidt (1940-2024)

Neil Edward Goldschmidt, the thirty-third governor of Oregon (1986-1991…

-

![Pioneer Courthouse Square]()

Pioneer Courthouse Square

In the heart of downtown Portland, Pioneer Courthouse Square fulfills i…

-

![Portland]()

Portland

Portland, with a 2020 population of 652,503 within its city limits and …

-

![Richard “Dick” Bogle (1930–2010)]()

Richard “Dick” Bogle (1930–2010)

Dick Bogle was a multi-talented Oregonian and humanitarian who dedicate…

-

![Ronald D. Herndon (1945–)]()

Ronald D. Herndon (1945–)

Firebrand. Activist. A modest man. Ron Herndon has been described as al…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.