One of America’s best-known photographers, Dorothea Lange captured some of the most evocative and recognizable images of Oregon during the Great Depression. From 1935 to 1939, she worked as a field investigator and photographer with the Resettlement Administration, a New Deal agency that was subsumed by the new Farm Security Administration in 1937. In the late summer and fall of 1939, Lange traveled through the Pacific Northwest, producing over five hundred photographs of the people and rural environment of the Columbia Basin, Willamette Valley, the Rogue River Valley, the Klamath Basin, and Malheur County. These photos, along with Lange’s terse yet observant captions, provide a rare glimpse of the social and cultural realities of rural Oregon during the Depression.

Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn was born on May 25, 1895, in Hoboken, New Jersey. Determined to be a camera artist, Lange found work as a photographer’s assistant in New York studios and took classes at Columbia University with Clarence White, a noted fine-art photographer and educator. After adopting her mother’s maiden name, she moved to San Francisco in 1918, where she established a studio specializing in portraits of the social elite. In 1920, she married western artist Maynard Dixon (1875-1946); the couple had two sons.

By the early 1930s, Lange’s populist sensibilities took her into the streets to record images of poor, unemployed, and migrant families. Her photos caught the eye of Berkeley economist Paul Schuster Taylor, who arranged for her to work as a field investigator and photographer for the newly formed Resettlement Administration. Lange and Dixon divorced in 1935, and she married Taylor the same year. Together, the couple crafted an illustrated study of Dust Bowl migrants, published in 1940 as An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion.

According to fellow RA and FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein, the purpose of the agency’s photography project was to “document the problems of the Depression, so that we could justify the New Deal Legislation that was designed to alleviate them.” Roy Stryker, head of the RA’s Historical Section, stipulated that no photograph should ridicule its subject or present a cliché. He also instructed photographers to temper their depictions of rural poverty with images that suggested the persistence of traditional values and familial bonds. Lange focused on migrant families in her work for the project. Her photograph Migrant Mother (1936), taken in Nipomo, California, remains one of the most iconic images of the Depression.

In August 1939, Lange arrived in Grants Pass to begin documenting farming operations, small towns, and labor camps throughout Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Her field notes describe her subjects’ lives and places and capture her subjects’ attitudes and humor. Her Oregon images reflect Lange’s view that all individuals—farmers, farmworkers, and small-town residents—were or could become citizens with the hope of creating a just and egalitarian society. Lange also detected widespread fear and hostility in Oregon toward labor organizers and the New Deal. And although she believed in the potential of federal projects, she also documented the anger and resentment many Oregonians felt toward the federal government.

Lange’s photographs of Merrill, Oregon, in October 1939 were her last as an FSA employee. On October 28, Stryker fired her, claiming budgetary issues. Returning to her home in Berkeley, she completed her field notes and finished her assignment on November 30, 1939. Violating an FSA stricture, Lange used real names in the captions for her Malheur County photographs to give dignity to her subjects. In 1940, many of her Oregon photographs were published in the Northwest Regional Council’s book, Caravans to the Northwest, which was adopted as a textbook in public schools in Seattle, Spokane, and Portland.

Dorothea Lange continued to take remarkable photographs, documenting the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans in 1942, working on assignment for Fortune and Life magazines in the 1940s and 1950s, and traveling to other countries. Shortly before her death from cancer on October 11, 1965, John Szarkowski, the curator of photography for New York’s Museum of Modern Art, proposed a major Lange retrospective, the first for a woman photographer at that venue.

-

![]()

Dorothea Lange, 1936.

Courtesy Library of Congress, CPH 3c28944

-

![Young mother and children.]()

Klamath Falls, 1939.

Young mother and children. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-021000-E

-

![Migrant child in a bean picker's camp.]()

West Stayton, Oregon.

Migrant child in a bean picker's camp. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-020583-C

-

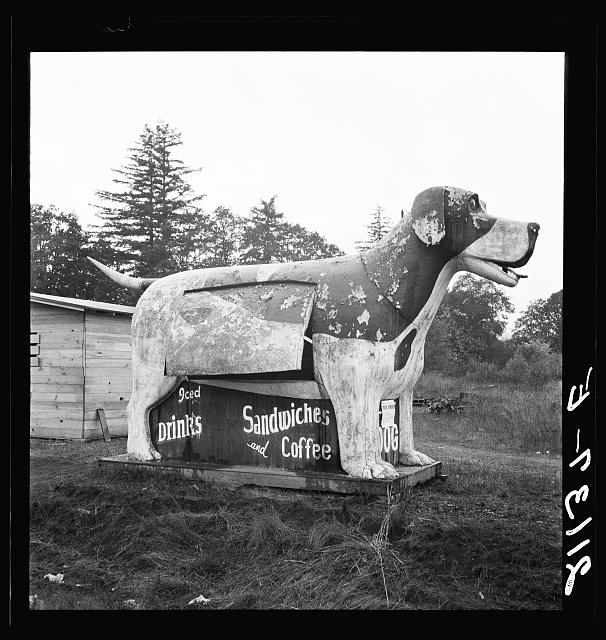

![]()

Highway 99, Lane County.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-021137-E

-

![Farmer and children from Albany, Oregon, in Marion County for bean-picking season.]()

Marion County.

Farmer and children from Albany, Oregon, in Marion County for bean-picking season. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, FSA 8b34472r

-

![Young migrant mother at the Farm Security Administration camp in Klamath County]()

Klamath County, 1939.

Young migrant mother at the Farm Security Administration camp in Klamath County Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-021819-E

-

![A man guides logs from the mill pond to the chute, Pelican Bay Lumber Co.]()

"Pond monkey," Klamath Falls, 1939.

A man guides logs from the mill pond to the chute, Pelican Bay Lumber Co. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-020618-E

-

![Children worked in the hops fields, all day and every day, during picking season (from Lange's notes).]()

Polk County.

Children worked in the hops fields, all day and every day, during picking season (from Lange's notes). Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, FSA 8b34576r

-

![Migratory field worker picks hops.]()

Independence, Polk County, 1939.

Migratory field worker picks hops. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-020672-E

-

![Couple digging sweet potatoes.]()

Irrigon, Morrow County, 1939.

Couple digging sweet potatoes. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-021077-C

-

![Members of the "Helping Hand" club roll up a quilt they are making, near West Carlton.]()

Yamhill County, 1939.

Members of the "Helping Hand" club roll up a quilt they are making, near West Carlton. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-021110-C

-

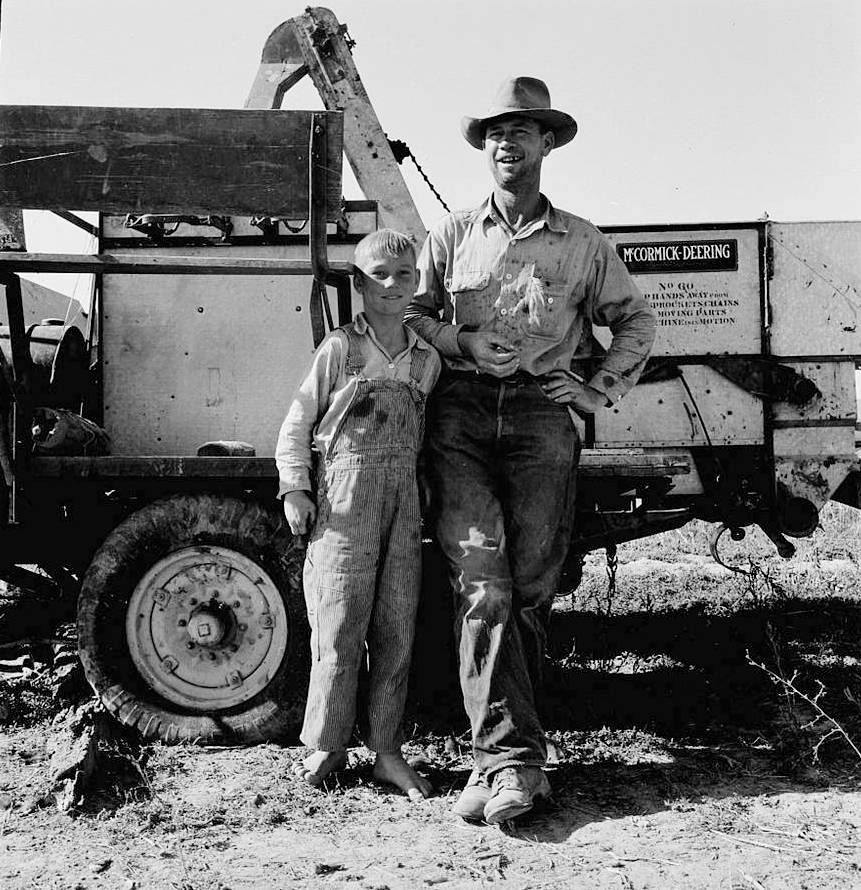

![George Cleaver and his son on their farm.]()

Malheur County, 1939.

George Cleaver and his son on their farm. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-021413-E

-

![Migrant family cleaning up camp.]()

Vale, Malheur County.

Migrant family cleaning up camp. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, FSA 8b35218r

-

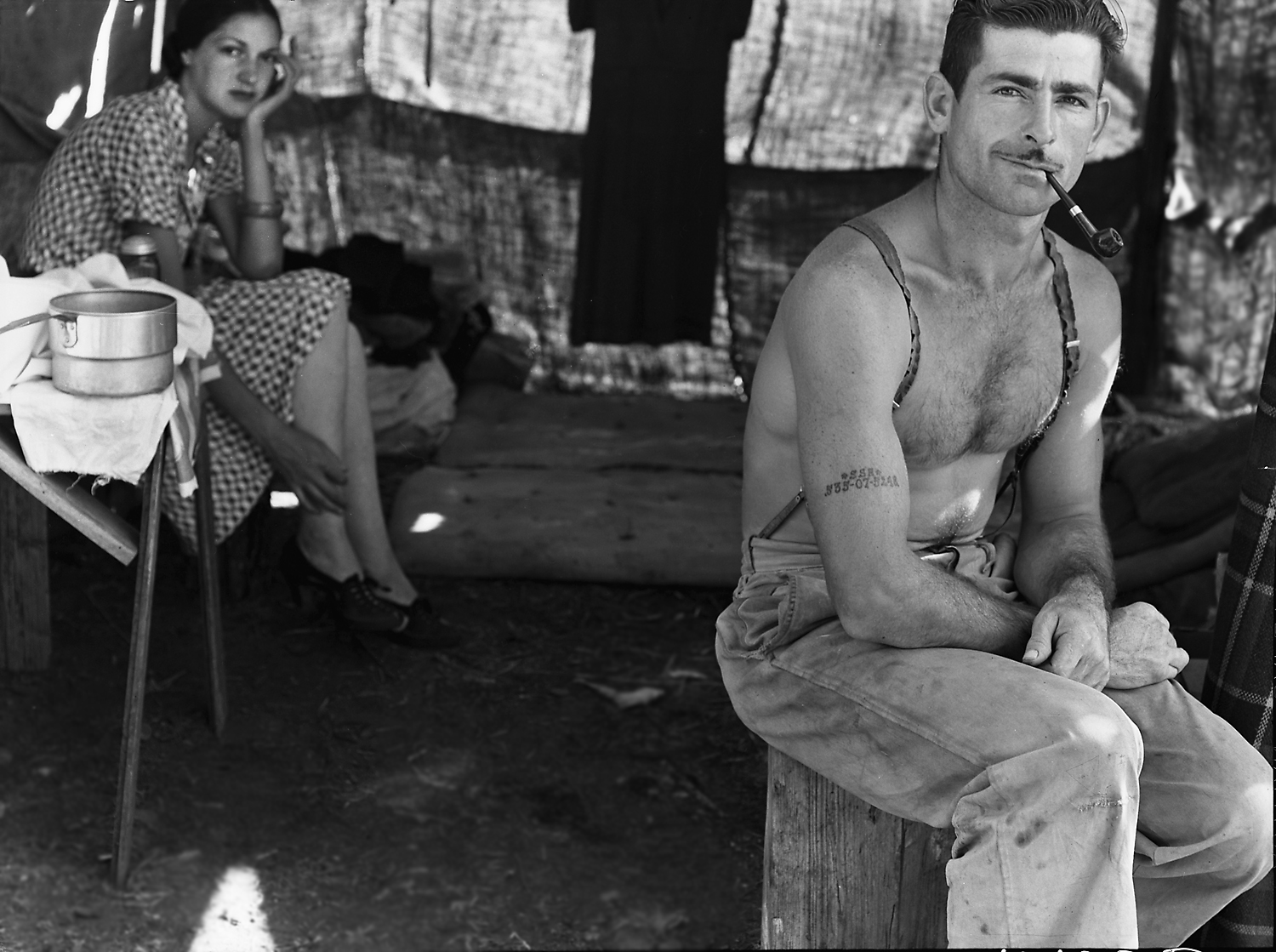

![Note social security number tattooed on right arm.]()

Unemployed lumber worker in bean picker camp.

Note social security number tattooed on right arm. Courtesy Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, LC-USF34-020908-D

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Gordon, Linda. "Dorothea Lange's Oregon Photography: Assumptions Challenged." Oregon Historical Quarterly 110.4 (Winter 2009): 570-595.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. Daring to Look: Dorothea Lange’s Photographs and Reports from the Field. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Gordon, Linda. Dorothea Lange: A Life beyond Limits. New York: W.W. Norton Co., 2010.

Gordon, Linda. Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. New York: W.W. Norton Co., 2006.