Portland staged its first and only world's fair from June 1 through October 15, 1905. During those four and a half months, 1,588,000 paying visitors passed through the gates to the 400-acre fairgrounds on the northwest edge of town. More than 400,000 were from outside the Pacific Northwest, a huge number of tourists for a city of perhaps 120,000 people.

Two years of landscaping had turned Guild's Lake, a marshy slough surrounded by dairies and truck farms, into building sites and terraces that led to a sparkling lake kept fresh with a constant flow of water pumped from the Willamette River. The exhibition halls went up on the bluff overlooking Guild's Lake and on a peninsula accessed by the Bridge of Nations. The whitewashed buildings against the green hills, said Mayor George H. Williams, was like "a diamond set in a coronet of emeralds."

The Lewis and Clark Exposition was conceived so Portland could demonstrate that it could mount a major civic enterprise. The city had had a solid record of economic growth since its founding in 1845, but at the turn of the twentieth century it was competing for investment and immigration with dozens of other cities throughout the American West—nearby Seattle, Spokane, Tacoma, Bellingham, and Everett and with more distant places such as Denver, Oakland, and San Diego. A successful world's fair would enhance the city's reputation as a safe and sound place to do business.

Portlanders also had another incentive. The fair event came only a year after St. Louis had hosted the enormously successful Louisiana Purchase Exposition. St. Louis was one of the most important cities in the country, and organizers believed that a fair that held its own with the Missouri metropolis would do wonders for Portland's reputation.

The exposition was expected to boost to the regional economy. Visitors would spend money on train tickets, hotel rooms, food, and drink, and the Northern Pacific Railroad and brewer Henry Weinhard were among the biggest financial backers. They would also learn about the natural resources of the Northwest and recognize how close Portland was to the markets of East Asia, which were attracting attention after the recent U.S. acquisitions of Hawaii and the Philippines. Although few people ever used it, the official name was Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair.

Like all of the other expositions during a century of world's fairs—from the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851 to the New York and San Francisco world's fairs of 1939-1940—the Lewis and Clark Exposition was a showcase for progress and people visited world's fairs to learn about scientific and technological advances. In Portland, they could take in moving picture shows, watch motorized blimps maneuver in the sky, cheer the winner of the first transcontinental auto race, and marvel at the power of electric lighting.

The social progress demonstrated by the fair was more complex. A racist exhibit of Filipino "savages" along the fair's amusement trail contrasted with the forward-looking speeches at the American Woman Suffrage Association convention. The official program for Portland Day showed a lone Indian looking down from the hills at the fairgrounds, a reminder of the power of European Americans.

Visitors to the exhibition pavilions saw the themes of prosperity and progress in multiple variations. The Oriental Exhibits and Foreign Exhibits pavilions highlighted the possibilities of foreign trade, and Japan's million-dollar exhibit was the largest among the twenty-one participating nations. The Palace of Agriculture showed the bounty of the western land. In the Oregon Building, counties showed off grain, fruit, canned good, minerals, and myrtle wood furniture. The towering Forestry Building, a "log cathedral" made from huge unpeeled Douglas-fir trunks, testified to the potential of the Northwest lumber industry. Separate buildings for Manufacturing and for Electricity, Machinery, and Transportation displayed the latest products of technical ingenuity.

The U.S. Government Building summarized the themes of prosperity and progress. A working model of the new Palouse irrigation project in eastern Washington, a relief model of the Klamath Basin reclamation project in southern Oregon, and a fish hatchery demonstrated how engineering and science could enhance regional growth. Panoramas of the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone Falls looked forward to the expansion of western tourism. Naval displays were a reminder that the United States had become a Pacific military power.

Portland's leaders hoped that the Lewis and Clark Exposition would garner reams of favorable publicity. When they emblazoned "Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way" on the arch over the entrance gate, they anticipated that visitors would see that empire was making its way westward to Oregon. And it was a success. Journalists from the East Coast called the Exposition "Portland's pride" and commented that "the whole fair is a successful effort to express . . . the natural richness of the country and its relative nearness to Asia."

-

![]()

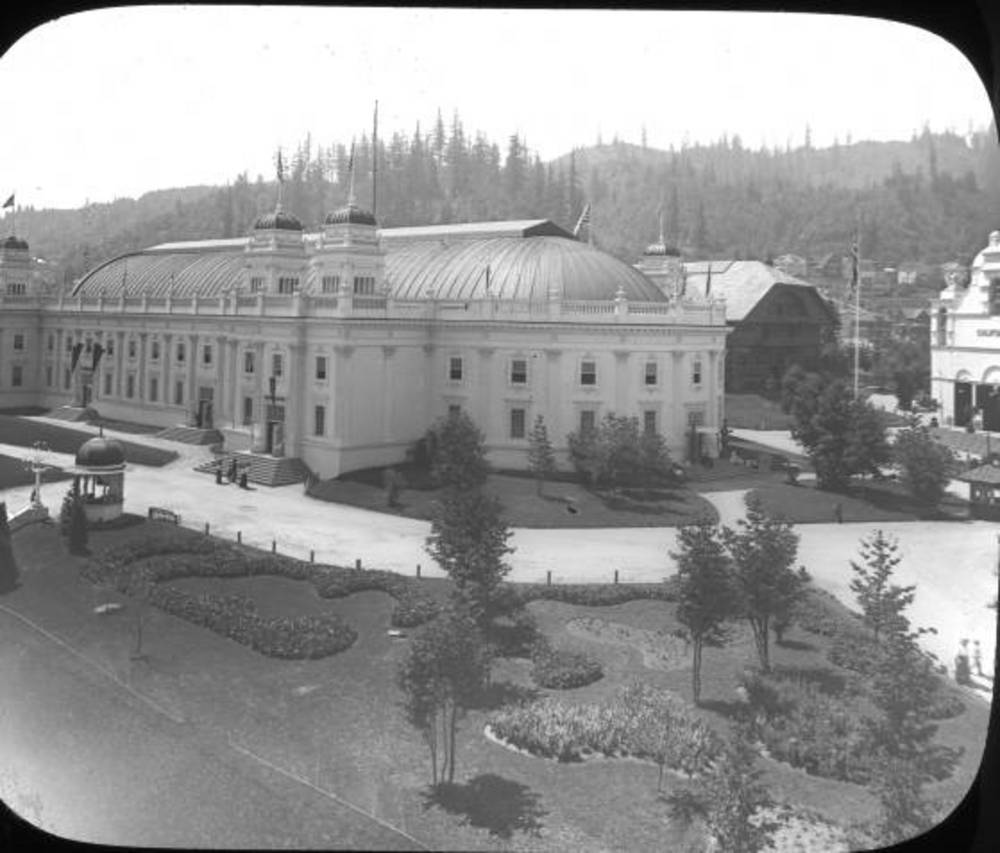

Oriental Building at the Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Visual Instruction Dept. Lantern Slides, P217:49_14

-

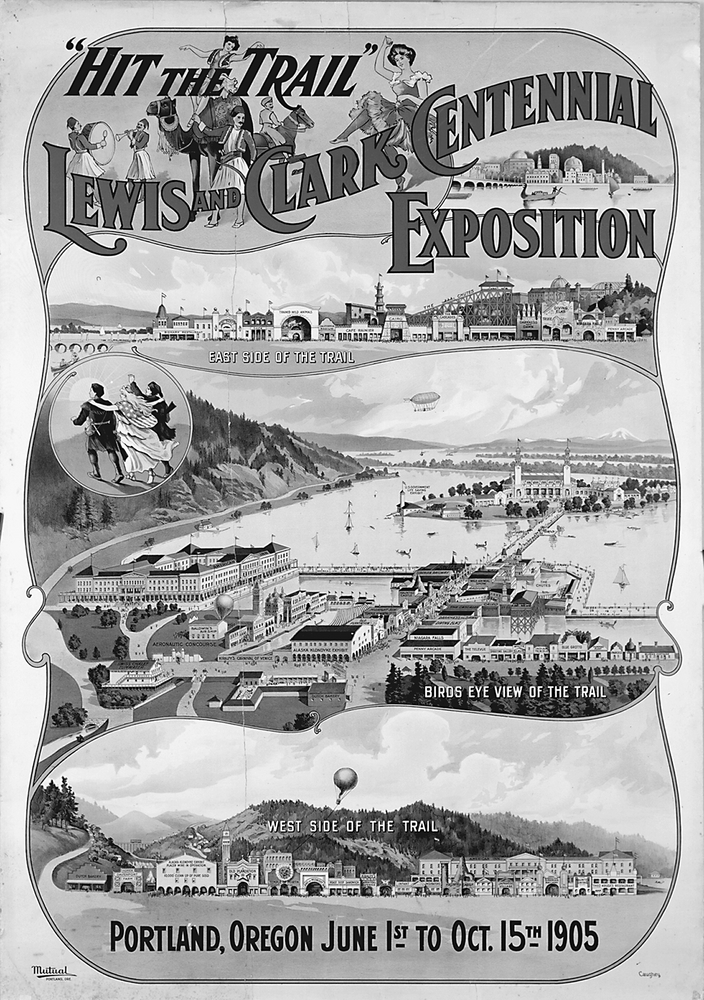

"Hit the Trail" poster for the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

-

Forestry Building at Lewis and Clark Exposition, Portland, 1905.

-

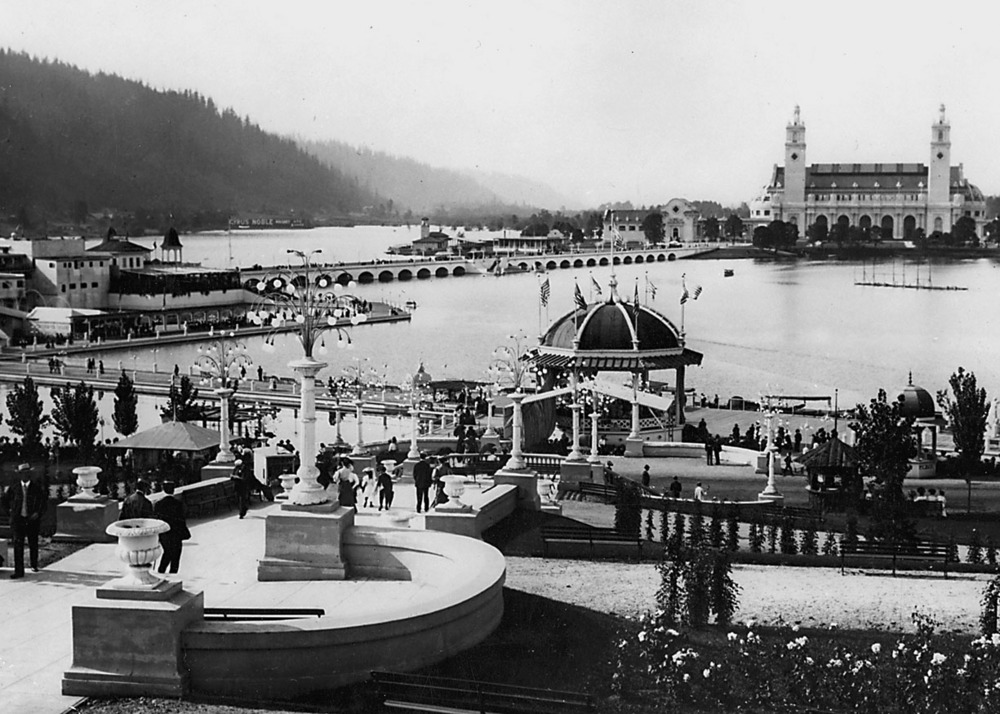

Entry colonnade at 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 46163

-

![]()

Airship at Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 11005

-

![]()

Bandstand at the Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

Oregon Historical Society Research Lib., OrHi 25137

-

![]()

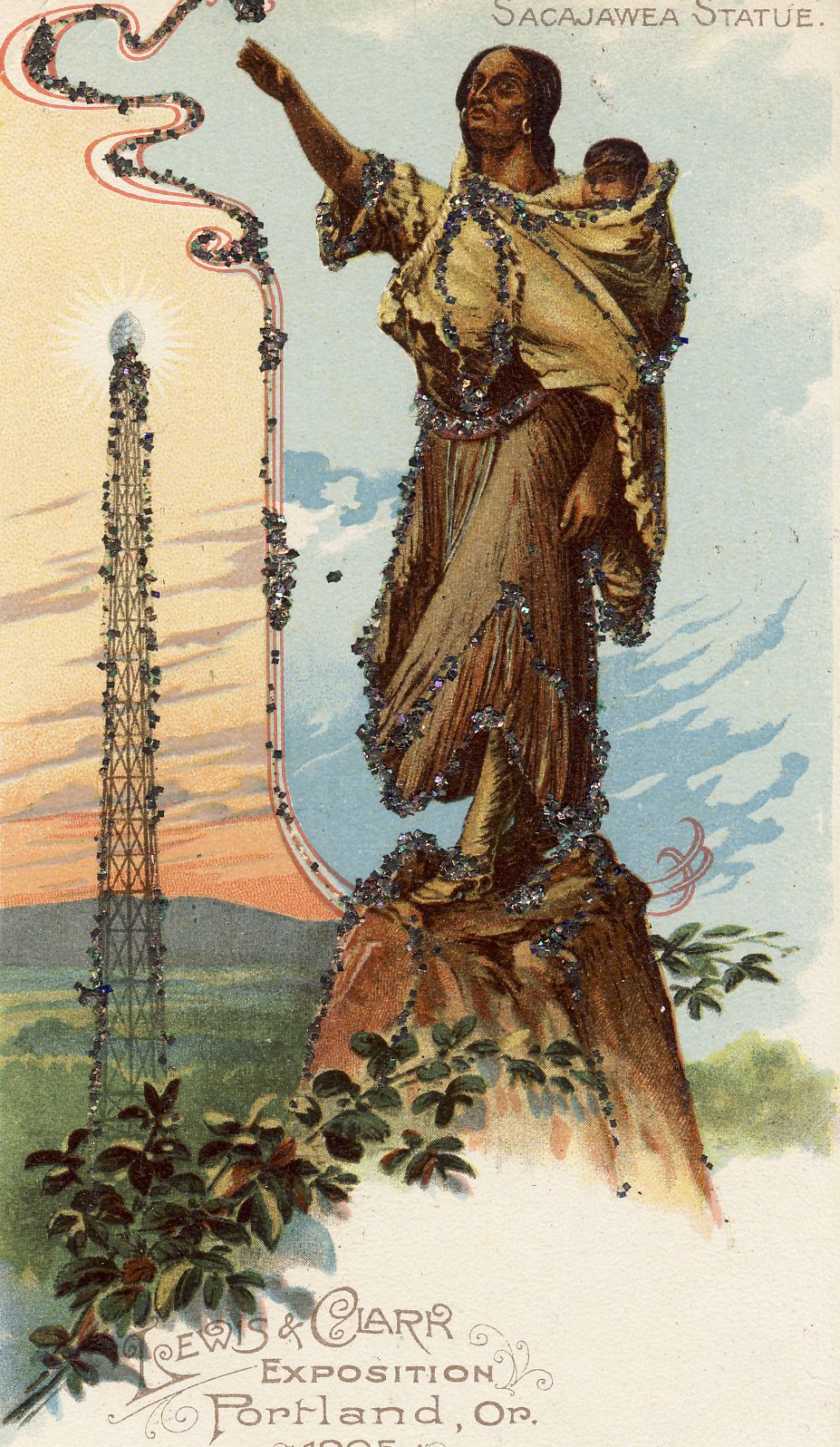

Color postcard of the Sacagawea statue at 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition.

Courtesy Robert L. Hamm

-

![]()

Souvenir program of Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 47307

-

![]()

Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 59607

-

Lewis and Clark Exposition, Portland, 1905.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 95010

-

![]()

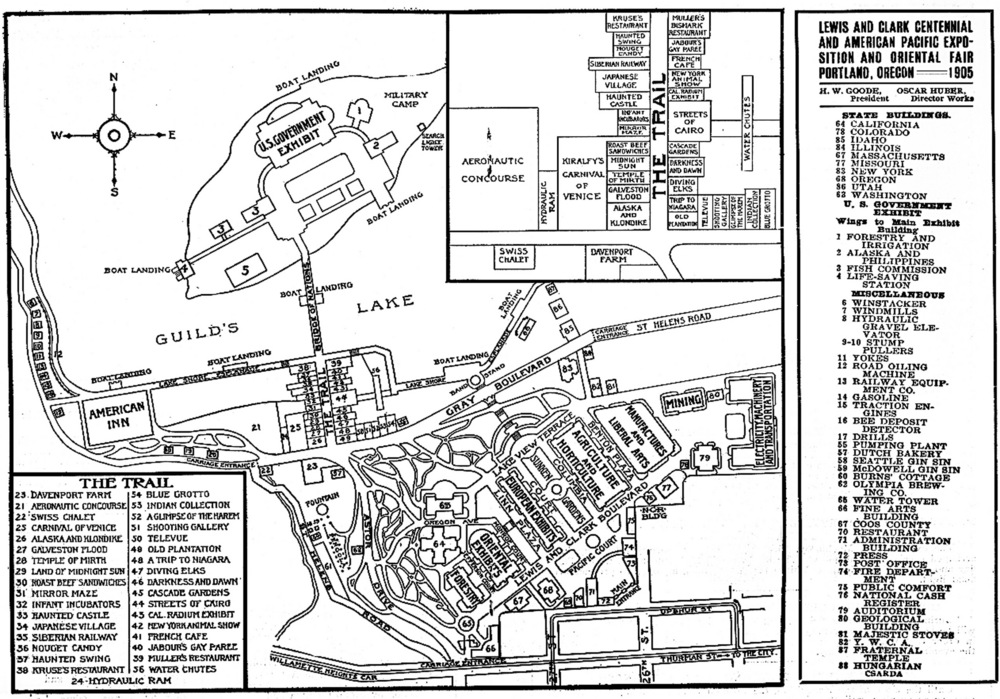

Map of Lewis and Clark Exposition, 1905.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 093615

Related Entries

-

![Guild's Lake]()

Guild's Lake

Today, the curve of St. Helens Road in northwest Portland skirts the ed…

-

![Lewis and Clark Bicentennial]()

Lewis and Clark Bicentennial

At least ten years before 2004, the 200th anniversary of Meriwether Lew…

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

Montgomery Ward/Park Building

The Montgomery Ward building in northwest Portland was a hallmark of mo…

-

![Portland Rose Festival]()

Portland Rose Festival

In 1905, when Portland Mayor Harry Lane addressed a crowd at the Lewis …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abbott, Carl. The Great Extravaganza: Portland's Lewis and Clark Exposition. 3d ed. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2004.

Blee, Lisa. "Completing Lewis and Clark’s Westward March: Exhibiting a History of Empire at the 1905 Portland World’s Fair." Oregon Historcial Quarterly 106 (Summer 2005): 232-53.

Rydell, Robert. All the World's a Fair. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.