Lithia Park in Ashland is a good example of what Fredrick Law Olmsted called "the genius of place." The park rambles from the edge of the city, along Ashland Creek canyon, to the slopes of Mount Ashland. At 93 acres, it is large for a town of only 21,000, but the park hosts a million visitors a year. With its curving parkway and walkways, woodsy paths, cascading water and lakes, and its feel of serene retreat within the city, Lithia Park is a clear reflection of Olmsted's public park influence from the turn of the century. In 1982, 42 acres of the park were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

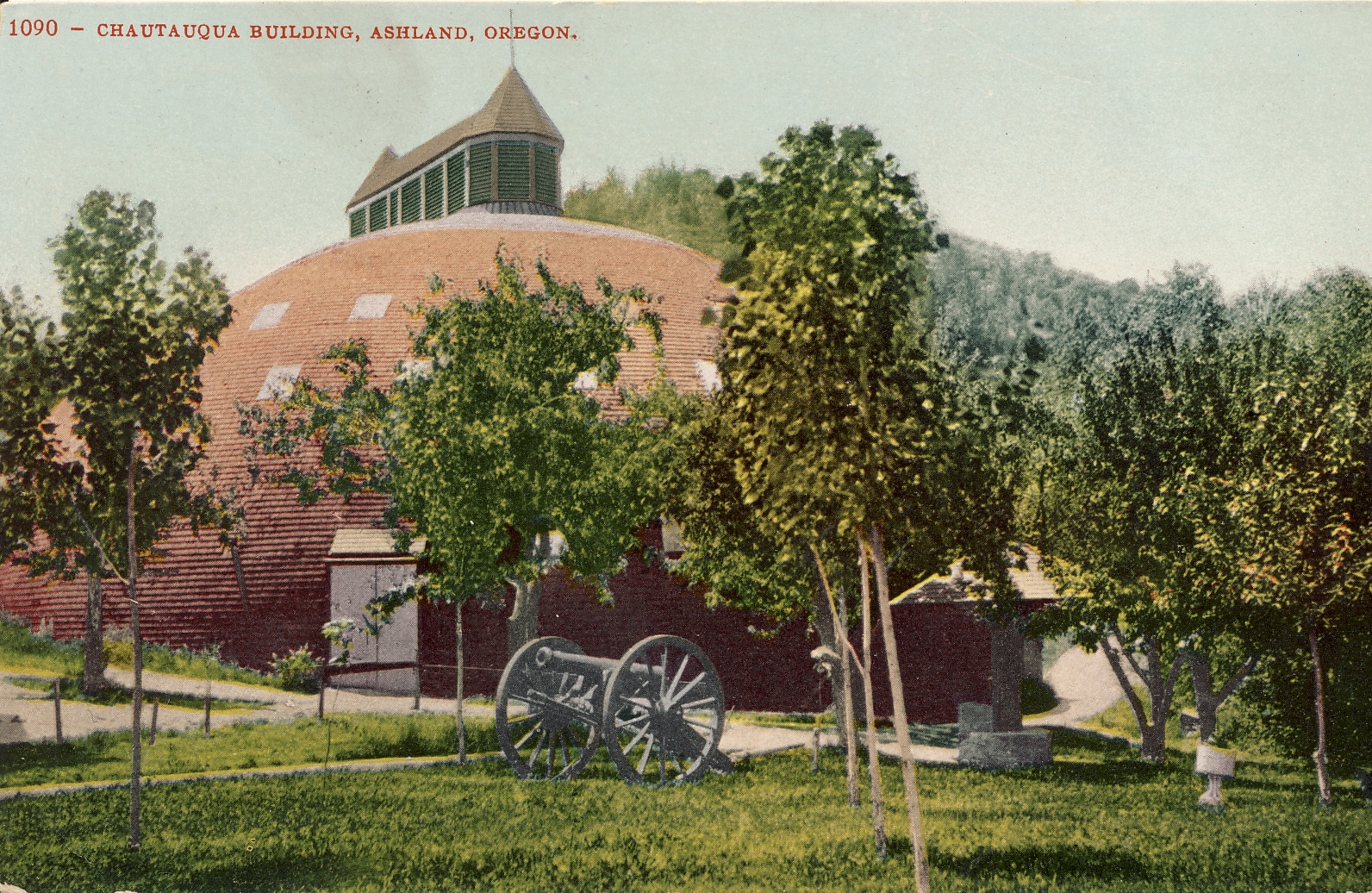

Lithia Park got its start in 1893, when Ashland's population was only 1,800, and the Southern Oregon Chautauqua Association created a performance venue above Ashland Creek. Its success led to beautification of the grounds, and in 1908 the citizens set aside all city-owned property on the creek for a park, authorizing a tax levy and a separate park commission. The city tore down a decrepit 1850s flouring mill on the plaza, its associated ill-smelling pigpens, cow barns, and remnants of an earlier sawmill, opening up the gateway to the canyon. After initial landscaping, the town became a tourist destination, known for both its seasonal Chautauqua and its beautiful park.

The next major step in development came in 1914, when Ashland Tidings editor Bert Greer, backed by the Southern Pacific Railway, promoted the idea of creating a health spa that would pipe local lithium-laced waters from natural springs several miles east of town. So seductive was this vision that he persuaded voters to pass a $175,000 bond issue, $65,000 of which (equal to $1.4 million in 2007 dollars) was to develop the park and provide elegant surroundings for this "Saratoga Springs" of the West.

While the spa concept was abandoned because of bitter political and financial controversies, the park flourished. The bonds were sold, and John McLaren, superintendent of Golden Gate Park, was hired as the landscaper. At a rally just before the bond election—described in the Tidings as "the greatest gathering ever held in Ashland"—McLaren declared that the canyon was "the most wonderful natural park" he had ever seen, with "little left to do except enhance nature's work." Landscaping was completed for 18 acres above Chautauqua Park, and 50,000 people, the Tidings estimated, attended the dedication on July 4-6, 1916.

McLaren's plan still forms the core of the park, with many of the trees—now a hundred years old—still in place. Also still remaining are the curving parkway, hiking paths, an upper lake, tennis courts, a Japanese garden, a neatly rowed sycamore grove, a formal terrace for the Italian marble fountain purchased at the 1915 Pan American Exposition, and a replica of one of the three original pavilions for mineral springs outlets.

Plantings in the park over the last one hundred years are a lush and diverse mix, reflecting the unique overlapping eco-systems of southern Oregon, and including non-native and exotic species from around the world—from carefully tended flowerbeds and an open grassy meadow, to canyon slopes wild with native ponderosa pine, California black and Oregon white oaks, manzanita and madrone, to masses of lush rhododendrons, towering giant sequoia, Chinese mulberry, monkey puzzle, ginkgo, shadowy maples of many varieties, a rare Dawn Redwood, willows, yews, cedars, and spruce.

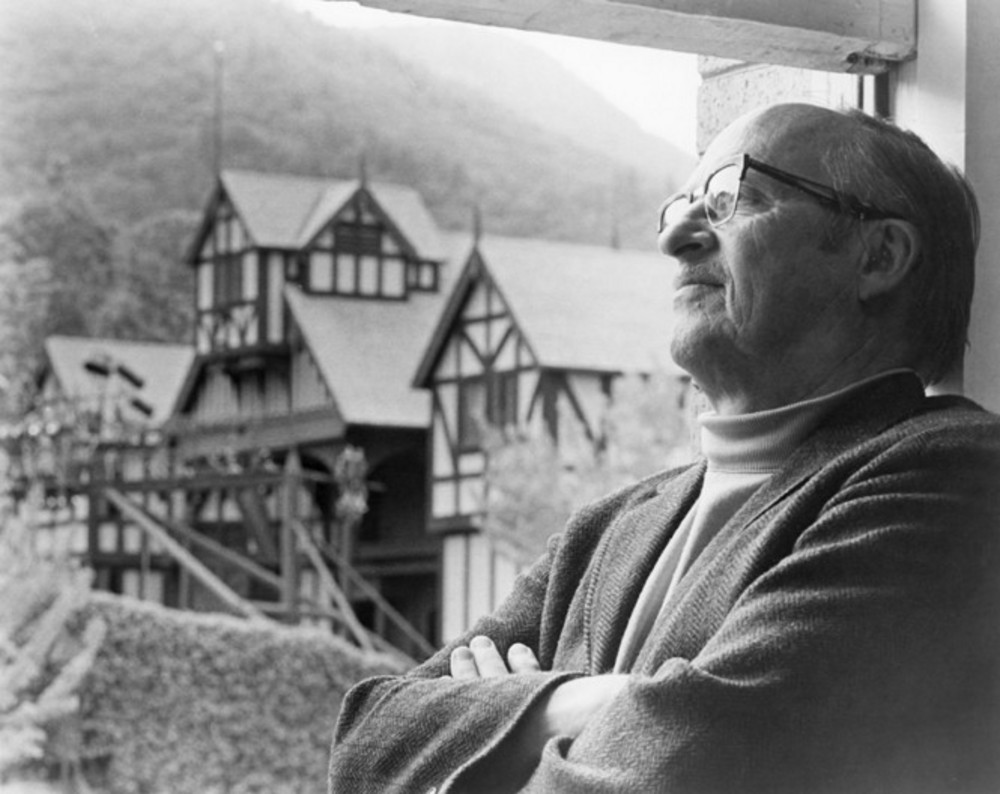

Lithia Park, according to the 1982 National Historic Places designation, is "significant primarily as the singular example of landscape design in Oregon by John McLaren." It is "a complete reflection of the public park movement," from its beginnings in the Chautauqua movement, to an Olmsted-style naturalistic park, to its improvements by the Works Project Administration between 1935 and 1938. Also of historic significance was the Free Auto Camp, developed in 1915 at the upper end of the park, one of the first such facilities on the West Coast. It was an "Auto Camp Delux," according to the American Motorist, journal of the newly minted AAA, with electricity, gas cooking plates, and hundreds of lights strung in trees. The park is also the original site of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival theater, which had its beginning in the old Chautauqua building in 1935.

Throughout its history, Lithia has withstood the erosive vicissitudes of politics, the Great Depression, wars, changing social values, the counter-culture movement of the 1960s, uprooting windstorms, and two major floods. It has evolved and expanded, but subsequent landscapers have held fast to John McLaren's original vision of nature enhanced. Lithia Park continues to be fiercely loved by residents and tourists alike. If the Shakespeare Festival is Ashland's economic heart, then Lithia Park is its soul.

-

![Lithia water fountain in Lithia Park, about 1913-1920.]()

Ashland, Lithia Park, water fountain.

Lithia water fountain in Lithia Park, about 1913-1920. Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_2177

-

![Camping at Lithia Park, Ashland, 1911.]()

Ashland, Lithia Park camping, 1911.

Camping at Lithia Park, Ashland, 1911. Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_2264

-

![Lumber yard at entrance of Lithia Park, about 1909-1910.]()

Ashland, Lithia Park entrance, lumber yard, ca 1909-1910.

Lumber yard at entrance of Lithia Park, about 1909-1910. Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_2400

Related Entries

-

![Ashland]()

Ashland

Ashland, a city of 21,360 people in Jackson County, is situated in the …

-

![Chautauqua in Oregon]()

Chautauqua in Oregon

An 1874 summer camp to train Methodist Sunday school teachers seems an …

-

![Oregon Shakespeare Festival]()

Oregon Shakespeare Festival

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF), under the leadership of Angus L.…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Aikman, Tom Girvan. Boss Gardner: The Life and Times of John McLaren. San Francisco: Don't Call It Frisco Press, 1988.

Mikelson, Kenneth J. National Register of Historic Places: Nomination Form, May, 1981.

O'Harra, Marjorie. Lithia Park. Ashland: Parks and Recreation Department, 1986.